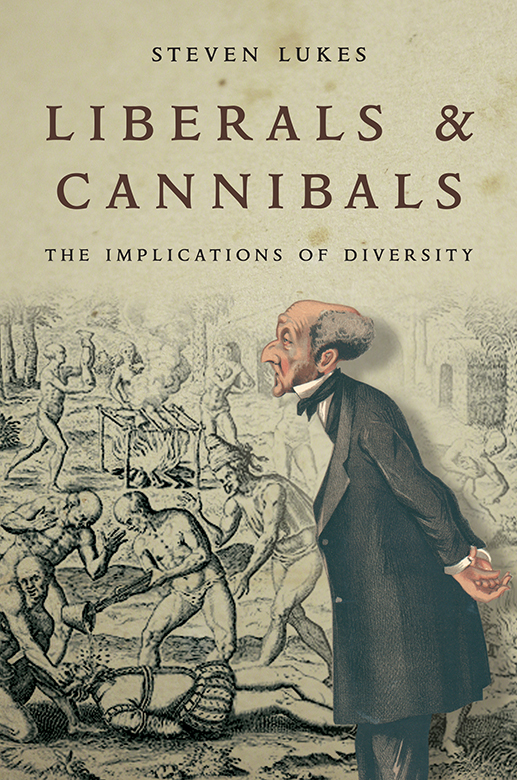

The pieces collected here were all published and/or delivered as lectures in the course of the last decade. Although diverse in style, tone, length and form, they all, in different ways, address a range of interconnected issues that emerged into ever greater prominence in the 1990s, issues raised by what is often, and with remarkable imprecision, called multiculturalism, and by identity politics. How are we to interpret the diversity of morals? To what extent is that diversity manifested between and to what extent within cultures? How extensive is it and how deep does it go? And what is the appropriate response? Is liberalism just another moral and cultural viewpoint? Is a liberal, as Robert Frost suggested, someone who cant take his own side in an argument? Is the appropriate response pluralism in matters of moral and political values and what does that mean exactly? How does it differ, if it does differ, from relativism? What is to be said for and against relativism? What challenge does it pose to the defence of human rights and how can that challenge be met?

These are some of the central questions concerning which these essays stake positions. Three of them focus on the thought of the late Sir Isaiah Berlin, critical engagement with which provides, I am convinced, a highly promising stimulus to their adequate construction and defence. Other essays concern themes from the 1990s that are still very much with us, both at home and across the globe, notably neo-liberalisms onslaught on the very idea of social justice and the dubious but resilient appeals of communitarianism and the politics of the third way.

Chapter 1 originally appeared in Journal of Philosophy of Education, vol. 29, no. 2, 1995; chapter 2 was delivered as the first Louis Henkin Lecture at Columbia University, New York in February 1998 and chapter 3 as the second Martin Hollis Memorial Lecture at the University of East Anglia in June 2001, appearing in Critical Reviews of Social and Political Philosophy, vol. 4, no. 4, Winter 2001; chapter 4 originally appeared in History of the Human Sciences, vol. 13, no. 1, February 2000; chapter 5 in Ruth Chang, ed., Incommensurability, Incomparability and Practical Reason, Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1997; chapter 6 in Social Research, vol. 61, no. 3, Fall 1994; chapter 7 in the Times Literary Supplement, 27 March 1998; chapter 8 in Ronald Dworkin, Mark Lilla and Robert B. Silvers, eds, The Legacy of Isaiah Berlin, New York: New York Review of Books, 2001; chapter 9 in Critical Review, vol. 11, no. 1, Winter 1997; chapter 10 in Social Research, vol. 64, no. 1, Spring 1997; chapter 11 (i) in Dissent, Spring 1998; chapter 11 (ii) in Contemporary Sociology, vol. 21, no. 4, 1992; chapter 12 in Stephen Shute and Susan Hurley, eds, On Human Rights The Oxford Amnesty Lectures 1993, New York: Basic Books, 1993; and chapter 13 in the Social Market Foundation Review, March 1999.

How should we react to the diversity of morals? What theoretical and practical conclusions should we draw from the ever more visible contrasts between ways of life between different practices and customs, between divergent perspectives on life and judgements about what makes it valuable, between divergent ways of responding to common problems that generate countless misunderstandings and conflicts that can end in wars?

This question has not always seemed puzzling. As I shall suggest below, the perception of moral diversity goes back at least to Antiquity, whereas the question of how to respond to it is rather modern. John Locke, for example, observed that there is scarce that Principle of Morality to be named, or Rule of Virtue to be thought on (those only excepted, that are absolutely necessary to hold Society together, which commonly too are neglected betwixt distinct Societies) which is not, somewhere or other, slighted and condemned by the general Fashion of whole societies of Men.

Religious faith is, indeed, one obvious basis on which the answer to the question I have asked will not seem puzzling or difficult but obvious. Another is that kind of Enlightenment rationalism, of when Locke was a forerunner, according to which the principles of morality can be discerned by the light of Reason, once Humanity has emerged from the darkness of dogma and removed the shadows of superstition. But in our time, when both religious and rationalist certainties are put in doubt, the very fact of moral diversity both across the world and within our increasingly pluralistic societies becomes disturbing. Can moral judgements be made across cultural boundaries? Do moral principles apply across divergent ways of life? Do our principles apply to them? Must moral criticism always be internal to a way of life? Is the very idea of a universal morality a pre-postmodern illusion?

Let me begin this inquiry by quoting a well-known passage from Herodotus, which is a favourite reference point in discussions of this set of issues. According to Herodotus, Darius, King of the Persians, took a wisely tolerant view of his subject peoples:

When Darius was King of Persia, he summoned the Greeks who happened to be present at his court, and asked them what they would take to eat the dead bodies of their fathers. They replied that they would not do it for any money in the world. Later, in the presence of the Greeks and through an interpreter (so that they could understand what was said) he asked some Indians, of the tribe called Callatiae, who do in fact eat their parents dead bodies, what they would take to burn them. They uttered a cry of horror and forbade him to mention such a dreadful thing. One can see by this what custom can do, and Pindar, in my opinion, was right when he called it king of all.

Several morals may be drawn from this familiar story. One I have already indicated: the fact of moral diversity is a very old story. Yet it does now appear differently and in contradictory ways. On the one hand, it is ever more perceptible and indeed omnipresent. Mass travel and modern mass communications make us all aware, on a daily basis, of the manifold differences between cultures across the world, and of clashes between them through television documentaries, plays and films and the mere reporting of the news. Mass immigration, trade and professional mobility across frontiers have made our societies ever more heterogeneous and polyglot Babels of languages, cuisines and customs. Yet we often see these developments through lenses that are themselves shaped by social and political processes. The differences are very often seen as lying between nationally or ethnically or racially defined communities, with the