All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

INTRODUCTION

Judith Mossman

Bild und Habitus der Intellektuellen ndern sich mit der jeweiligen Gesellschaft und den konkreten Aufgaben und Funktionen, die er in ihr wahrnimmt. Denn jede Zeit schafft sich die Intellektuellen, die sie braucht. Wir selbst haben einen solchen Wandel seit den spten 60er Jahren unmittelbar miterlebt. Der damals aktuelle Typus des kritischen, politisch und moralisch engagierten, linken Intellek tuellen, der weit ber Hrsaal und Universittscampus hinaus in der ffentlichen Diskussion und im Straenprotest das Bild bestimmte, ist heute ausgestorben und mit ihm auch ganz bestimmte Formen seines Erscheinungsbildes, von der unkonventionellen, am Arbeiter orientierten Kleidung bis hin zum Lebensstil und zur Redeweise. Die Konsumund Freizeitgesellschaft hat inzwischen lngst neue Typen hervorgebracht: den politisch nicht mehr engagierten Moderator, den Unterhalter, den Analytiker und Prognostiker, der Zeitstrmungen zu erkennen und im Dienste seiner Auftraggeber eventuell auch zu modellieren versucht. Nicht mehr der parteiische Kritiker und Re former, sondern der mehr oder weniger konformistische, ber den Parteien stehende Kommentator ist gefragt.

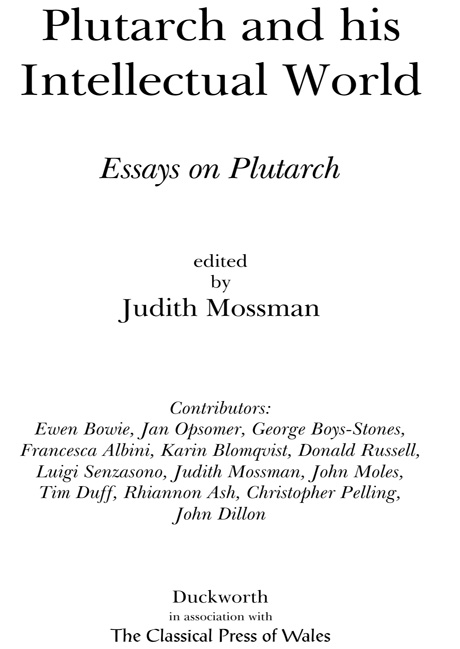

The naming of books is a difficult matter, especially the naming of collections of essays. There is a danger that any title general enough to be properly descriptive of the contents of such a book may sound woolly; the danger is all the greater if the title includes a word like intellectual, a word with a number of different shades of meaning and connotations which are not always either clear or positive. As this collection of essays is called Plutarch and his Intellectual World , it seems doubly necessary for the editor to explain in some detail the rationale behind this title.

It was meant to convey various ideas, exploiting rather than suffer ing from the ambiguities of intellectual. First, it was supposed to suggest that Plutarch has an intellectual historical context which he responded to, which he helped to shape and was shaped by, and in which he needs to be understood. Secondly, I wanted to emphasise,

But there is something else lurking in this title, too: the question, In what sense is Plutarch an intellectual?, is raised by it, but not an swered. Indeed, there is no single answer, but many perhaps as many as there are readers of Plutarch. If Plutarch himself were asked what sort of an intellectual he was, it is far from clear that he would recognise the terms of the question, leave alone what he would want to answer.

Zankers description of the intellectuals of today in the quotation above says much that is reminiscent of Plutarchs apparent attitude to the proper role of the intellectual in the wider world; and John Dillon, too, in the final essay in this collection, strongly suggests that Plutarch and contemporary thinkers such as Fukuyama have similar views of themselves as observers of the end of history.rather the case that each successive age finds in Plutarch what it needs, just as it creates the contemporary intellectuals it requires.

Bearing all this in mind, it seemed best to begin the collection with three studies on Plutarchs relations with his contemporaries the historical context of Plutarchs intellectual world, in effect. Ewen Bowie considers the relationship of Plutarch to Favorinus and of Favorinus to Hadrian; Jan Opsomer and George Boys-Stones tackle different aspects of Plutarchs engagement in philosophical debate and seek to elucidate Plutarchs own philosophical position.

From Plutarchs philosophy to his views on society: Francesca Albini next considers aspects of Plutarchs thought on education, that fundamental component of anyones intellectual outlook; Karin Blomqvist raises Plutarchs attitude to gender and specifically to how women should use their talents, intellectual and other, and what those talents are.

Moving from Plutarchs thought to his mode of expression, some thing he considered vital to the appreciation of character and intel lect, Donald Russell shows in a detailed study of a high-point of one of Plutarchs most carefully written works how Plutarch constructs an argument and expresses it.

The next two essays concentrate on further literary aspects of two of the Moralia : Luigi Senzasono examines a nexus of imagery which links health and politics in the De tuenda sanitate praecepta , and I examine the literary antecedents and method of the Dinner of the Seven Wise Men .

Turning to the Lives , Plutarchs appreciation and use of his primary sources is considered by John Moles in a manner which stresses how artful Plutarch can be even when he is apparently at his most ingenu ous; this is also emphasised in a somewhat different context by Tim Duff in his examination of Plutarchs moralism. Rhiannon Ash and Christopher Pelling illustrate different aspects of Plutarchs depth and subtlety of historical vision and how he uses sophisticated literary techniques to convey it, and finally John Dillon reinforces the point that Plutarch is capable of seeing, indeed compelled to see, his own times as part of a broader historical perspective.

It is hoped that some of the breadth and variety of Plutarchs intellectual interests and some of the skill with which they are ex pressed will become clear from the thirteen essays in this book. But so versatile was Plutarchs intelligence, and so great his intellectual en ergy, that one collection of essays cannot hope to do full justice to him; there is still much scope yet for exploration of Plutarch and his intellectual world.

Notes

Paul Zanker, Die Maske des Sokrates: Das Bild der Intellektuellen in der antiken Kunst , Munich 1995, 9: The image and dress of the intellectual change with contemporary society and the concrete tasks and functions which he undertakes in it. For each society creates the intellectuals it needs. We ourselves have directly experienced such a change since the late 60s. The type of the intellectual current at that time the critically, politically, and morally engaged, left-wing intellectual, who established his image far beyond the lecture room and university campus through public discussion and protestmarches in the street has died out today, and with him also quite distinctive patterns in his outward image, from his unconventional, worker-oriented clothing to his mode of living and the style of his discourse. The consumerand leisure-society has in the meantime long since produced new types: the TV anchor-man, no longer politically engaged, the chatterer, the analyst and pundit, who tries to recognise contemporary tendencies and in the service of his employers eventually also tries to mould them. No longer the partisan critic and reformer, but the more or less conformist commentator, who stands above the parties, is in demand.