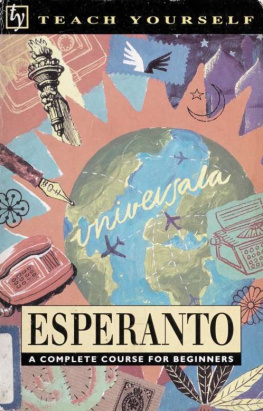

Esther Schor - Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language

Here you can read online Esther Schor - Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Metropolitan Books, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language

- Author:

- Publisher:Metropolitan Books

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Esther Schor: author's other books

Who wrote Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

al samideanoj pasintaj kaj nuntempaj,

KORAN, VERDAN DANKON

to Esperantists past and present,

GREEN AND HEARTFELT THANKS

It is not down in any map; true places never are.

H ERMAN M ELVILLE, Moby-Dick

Because I have used pseudonyms for most of the Esperantists mentioned, I have reversed the usual practice of using asterisks to indicate pseudonyms. Thus pseudonyms appear without asterisks, and asterisks are reserved for actual names (at first mention). Historical figures and cited authors are referred to by their actual names, without asterisks.

All translations from Esperanto are my own, except where otherwise indicated in the notes.

On the muggy July afternoon when I visited the Okopowa Street Cemetery, the dead Jews whod slept on while the Nazis packed their descendants into cattle cars bound for Treblinka were still asleep. After hours tracking the contours of the Ghetto behind a detachment of Israeli soldiers, I was relieved to be among the lush ferns, rusted grilles, and mossy stones. Here and there, tipped and broken monuments had settled where theyd fallen among yellow wallflowers. In other sections, weeded, swept, and immaculately tended, huge monuments incised with Hebrew characters bore a heavy load of sculpted fruits, animals, priestly hands, and the tools of trades. The stones were cool to the touch, amid a musky odor of rotting leaves.

Among the largest monuments in the cemeterythe baroque monument to the actor Ester Rachel Kamiska; the porphyry stone of writer I. L. Peretz; the ponderous granite tomb of Adam Czerniakw, who after pleading in vain for the lives of the Ghettos orphans took his ownwas a large sarcophagus. On top rested a stone sphere the size of a bowling ball. Below a ledge of marble chips planted with plastic begonias was a large mosaic, a sea-green star with a white letter E at the center. Rays of blue, red, and white flared out in all directions. It was gaudy and amateurish, awkward in execution. The inscription read:

DOKTORO LAZARO LVDOVIKO ZAMENHOF KREINTO DE ESPERANTO

NASKITA 15. XII. 1859. MORTIS 14. IV. 1917

Esperanto: I recalled one glancing encounter with it when I was twenty-three, an American in self-imposed exile, living in a chilly flat in London. The reign of Sid Vicious was about to be usurped by Margaret Thatcher, and the pittance I earned in publishing was just enough to buy standing room at Friday matinees and an occasional splurge on mascara. My boyfriend, Leo, and I found a rock-bottom price for a week in the Soviet Union; the only catch was that January, the cheapest time of the year to go, was also the coldest: in Moscow, 28 degrees Fahrenheit below; in Leningrad, a balmy zero. Leo took his parka out of storage; I borrowed warm boots, a fake-fur coat, and a real fur hat, and off we went. (In fact, I found it much warmer in the Soviet Union than in London, at least insidechalk that up to central heating, which I could not afford.)

At the Hermitage, I wandered over to a large, amber-hued painting labeled . Pembrandt?no, Rembrandt . A prodigal myself, I recognized it as a painting of the Prodigal Son, a young man kneeling in the embrace of a red-caped patriarch. As I drew closer to the supplicant, I noticed he had an admirer besides me: a tall, slender woman about my age with wispy bangs, stylish boots, and a brown wool coat. The previous day, a well-coiffed Intourist guide had explained to me that there were three kinds of women in Russia: women with fur hats, women with fur collars, andshe paused for effectwomen with no fur at all. Here was one of the latter, and while I noted her furlessness, she greeted me in Russian..

Preevyet. Hello, I said.

She smiled. My name is Ekaterina, I am from Alma Ata. Where are you from? She seemed to be rummaging for more English words, but after Do you speak Esperanto? the pantry was bare.

Laughing, I asked, Franais? but she wasnt joking.

Ne , ne, she said deliberately, her gray eyes narrowing, Es-per-AN-to. One of us, I was sure, was ridiculous, but who? She, speaking to me in a pretend language? I, ignorant of Russian, Kazakh, and Esperanto, in my red Wellingtons, got up as Paddington Bear? Even as we shook hands and parted ways, the conversation was swiftly becoming an anecdote, a story to tell next week at the Swan over a pint of bitter.

Twenty-five years later, with prodigal sons of my own, I stood at what might have been, for all I knew, the grave of Esperanto itself, and thought of Ekaterina. Shed be in her late forties now, her forehead lined, her hair graying or, more likely, rinsed flame-red. Still furless, shed be stuck in a concrete high-rise in Alma Ata (now Almaty), where years pass slowly, heaving their burdens of debt and illness and worry. I wondered how Esperanto had journeyed from Poland to Kazakhstan, how long it had endured, and who had erected this monument. Who laid out this mosaic, chip by tiny chipmen? women? both? Jews? Poles? Kazakhs? Where had they come from, and when? And why such devotion to a failed cause, to the quixotic dream of a universal language?

I didnt know it then, but I would spend most of a decade trying to find out.

* * *

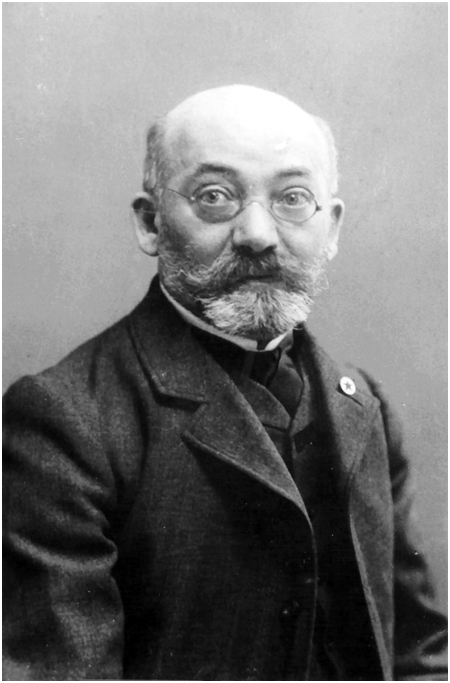

The man who called himself Doktoro Esperanto (Doctor Hopeful) was a modern Jew, a child of emancipation adrift between the Scylla of anti-Semitism and the Charybdis of assimilation. Ludovik Lazarus Zamenhof was born in 1859 in multiethnic Biaystok under the Russian Empire, the son and grandson of Russian-speaking language teachers. For a time, as a medical student in Moscow in the 1870s, he had dreamed among Zionists, but dreams are fickle things. His did not lead him to found a Jewish settlement in the malarial swamps and rocky fields of Palestine. In fact, they led him to dream of a Judaism purged of chosenness and nationalism; a modern Judaism in which Jews would embraceand, in turn, be embraced bylike-minded others bent on forging a new monotheistic ethical cult. He believed that a shared past was not necessary for those determined to remake the world, only a shared futureand the effort of his life was to forge a community that would realize his vision.

Had Zamenhof been one of the great God-arguers, hed have taken God back to the ruins of Babel for a good harangue. God had been rash (not to mention self-defeating) to ruin the human capacity to understand, and foolish to choose one nation on which to lavish his blessings and curses, his love and his jealousy. But Zamenhof was not an arguer. Benign and optimistic, he entreated his contemporaries, Jews and non-Jews alike, to become a people of the future. And to help them to cross the gulfs among ethnicities, religions, and cultures, he threw a plank across the abyss. As he wrote in The Essence and Future of an International Language (1903) :

Ludovik Lazarus Zamenhof, Doktoro Esperanto

[sterreichische Nationalbibliothek]

If two groups of people are separated by a stream and know that it would be very useful to communicate, and they see that planks for connecting the two banks lie right at hand, then one doesnt need to be a prophet to foresee with certainty that sooner or later a plank will be thrown over the stream and communication will be arranged. Its true that some time is ordinarily spent in wavering and this wavering is ordinarily caused by the most senseless pretexts: wise people say that the goal of arranging communication is childish, since no one is busy putting planks across the stream; experienced people say that their progenitors didnt put planks across the stream and therefore, it is utopian; learned people prove that communication can only be a natural matter and the human organism cant move itself over planks etc. Nonetheless, sooner or later, the plank is thrown across.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language»

Look at similar books to Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.