The Vanishing Middle Class

Prejudice and Power in a Dual Economy

Peter Temin

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2017 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Sabon LT Std by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Temin, Peter, author.

Title: The vanishing middle class : prejudice and power in a dual economy / Peter Temin.

Description: Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016035191 | ISBN 9780262036160 (hardcover : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780262339971

Subjects: LCSH: Income distribution--United States. | Middle class--United States--Economic conditions. | Minorities--United States--Economic conditions. | Equality--United States. | United States--Economic conditions--2009- | United States--Economic policy--2009

Classification: LCC HC110.I5 T455 2017 | DDC 339.2/208900973--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016035191

ePub Version 1.0

For Charlotte

My wife, companion, and muse for fifty years

Introduction

Growing income inequality is threatening the American middle class, and the middle class is vanishing before our eyes. There are fewer people in the middle of the American income distribution, and the country is dividing into rich and poor. Our income distribution has changed from looking like a one-humped camel to looking like a two-humped camel with a low part in between. We are still one country, but the stretch of incomes is fraying the unity of the nation.

The middle class was critical to the success of the United States in the twentieth century. It provided the manpower that enabled the nation to turn the corner to victory in two world wars in the first half of the century, and it was the backbone of American economic dominance of the world in the second half. But now the average worker has trouble finding a job, and the earnings of median-income workers have not risen for forty years. (The median income is the middle income, where as many people earn more as earn less; it was about $60,000 in 2014 for a family of three.) If America is to remain strong in the twenty-first century, something has to be done.

This problem is complicated by the influence of American history. Slavery was an integral part of the United States at its beginning, and it took a protracted and bloody Civil War to eliminate it. Too many African Americans still are not fully integrated into the mainstream of American society. While progress has been made, our neighborhoods and schools remain largely segregated by race, and African Americans as a whole are poorer than white Americans.

The combination of inequality and racial segregation is problematic for the health of our democracy. For example, it should be the right of any citizen to vote in a democracy. Slaves of course did not vote, and attempts continue to this day to keep African Americans from voting, including a number of high-profile cases of alleged illegal obstruction that have gone to the courts. In addition, black people are far more likely than white people to be arrested and sent to prison in the American War on Drugs.

Poor whites also have suffered in various ways, but they have remained mostly quiescent and invisible in political debates and decisions. Traditionally, poor white Americans have not voted much, due to the restrictions used to discourage black voting like requiring picture IDs, and widespread beliefs that political parties are all the same and politicians do not care about them. Their frustration and despair at being left out of recent economic growth has resulted in an array of stresses and self-destructive behaviors that have raised the death rates for middle-aged white Americans. Anger at their circumstances is being channeled into politics in 2016. This anger is likely to affect American politics for a long time.

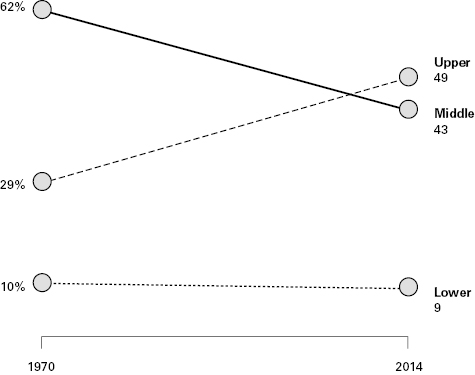

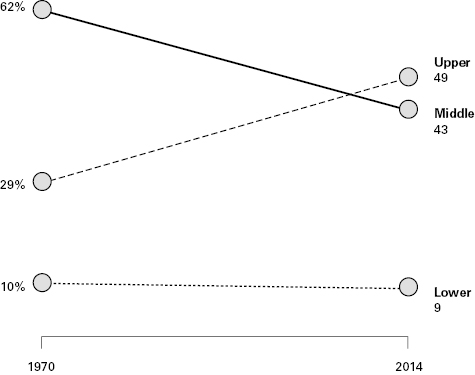

These developments were revealed dramatically in a recent study by the Pew Research Center. The change is shown in were horizontal before 1970, but they are continuing their movements after 2014.

Now we see that the income distribution is hollowing out. We are on our way to become a nation of the rich and the poor with only a few people in the middle.

Percent of aggregate U.S. household income. Note: The assignment to income tiers is based on size-adjusted household incomes in the year prior to the survey year. Shares may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding.

Source: Pew Research Center 2015

This book provides a way to think about this growing disparity of incomes between rich and poor. I argue that American history and politics have a lot to do with how our increasing inequality has been distributed. While our rapidly changing technology, prominently in finance and electronics, is an important part of this story, it is far from the whole tale. Our troubled racial history of slavery and its aftermath also plays an important part in how this growing divide is seen.

English settlers began coming to North America in the seventeenth century. They started in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and Jamestown, Virginia, and spread along the Atlantic seaboard. They found abundant and fertile land to farm, but there were not enough settlers and labor to farm as much land as they wanted. The resident Native Americans resisted working for the English occupiers and were decimated by European diseases. The settlers encouraged other people to come farm their land, and European and African population movements were attracted in very unequal ways. Europeans were encouraged to come by themselves or as indentured servants who became independent farmers, while Africans were brought against their will by slave traders.

Europeans gained great prosperity first from agriculture and then from industry, while Africans were condemned to slavery. Cotton was the key to economic growth in the early nineteenth centurygrown by African slaves in the South and manufactured into cloth by Europeans in the North. Slavery was abolished by the Civil War that remains unresolved in the minds of many white Southerners. European immigration was restricted after the First World War, and six million African Americans moved north during what was called the Great Migration as a result. In recent years, immigration from Mexico and other nearby Latin American countries has increased rapidly, and Latinos also are concentrated in the lower group shown in . Public discussion of the working poor focuses on African Americans, but it sometimes refers to them simply as them, including Latinos as well.

African Americans also have become the focus of policy debates at both state and federal levels. Politicians who oppose government welfare expenses used to identify the recipients as black; however, since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, politicians use code words instead. While nearly half of black Americans are included the poorer group in

Race and class are distinct, but they have interacted in complex ways from the U.S. slavery era that ended in 1865; to Ronald Reagan announcing his 1980 presidential campaign in Philadelphia in Mississippi, where three civil rights workers had been murdered in 1964; to Donald Trumps equally indirect claim to Make America Great Again in his 2016 presidential campaignwhere great is a euphemism for white. The Civil Rights Movement changed the language of racism without reducing its scope. As incomes become more and more unequal, racism becomes a tool for the rich to arouse poor whites to feel superior to blacks and distract them from their economic plight.

Next page