Mapping

Mars

OLIVER MORTON

Mapping

Mars

SCIENCE, IMAGINATION, AND

THE BIRTH OF A WORLD

PICADOR USA

NEW YORK

Copyright 2002 by Abq72 Ltd. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address Picador USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.picadorusa.com

Picador is a US registered trademark and is used by St. Martins Press under license from Pan Books Limited.

ISBN 0-312-24551-3 ISBN 978-0-312-24551-1

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate

First U.S. Edition: September 2002

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Lieutenant Arthur Noel Morton, RNVR

Navigating officer, HMS Hargood, 1944-45

Lover of maps, lover of writing and loving father

Round about here, Sir.

Contents

Are you going to move our stuff?

No, thats the view. Were in the picture.

Exchange between William Fox

and Mark Klett in William L. Fox,

View Finder

Introduction

Theres a world on my wall.

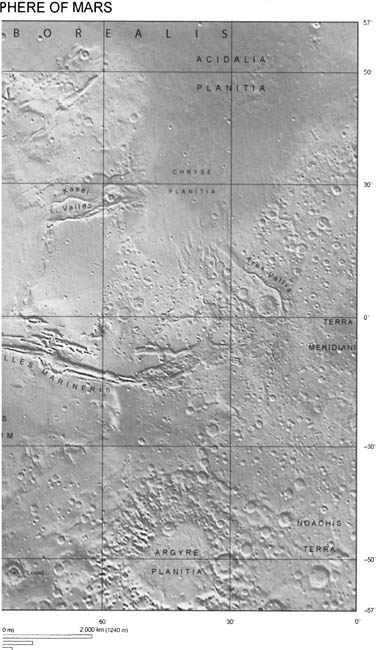

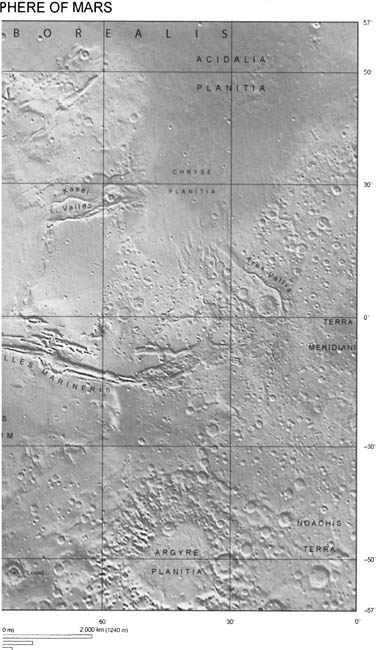

Mountains, canyons, plains, and valleys, all a faded pinkish ochre, an even tone as plain as a color can be without being gray. The sun is to the westshadows fall gently to the right. There are faults and rifts, ash flows and lava fields. There are creases and stretch marks, straight lines and strange curves. There are circles and circles and circles.

No cities. No seas. No forests and no battlegrounds. No prairies. No nations. No histories and no legends. No memories. Just features, features and names. Argyre and Hellas and Isidis. Olympus and Alba and Pavonis. Schiaparelli and Antoniadi, Kasei and Nirgal. Beautiful double-rimmed Lowell. Names from one world projected onto maps of another. Maps of Mars.

The maps on my wall, painstakingly painted about fifteen years ago, show the surface of Mars from pole to pole. They show volcanoes that dwarf their earthly cousins in age and size. They show the round scars of uncountable asteroid impacts, many far more violent than the one that killed off the Earths dinosaurs. They show a canyon so long and deep its as if the planets tight skin has swollen and split. They show featureless plains and pockmarked ones, jumbled hummocky hills and strange creases that swarm together for thousands of miles, like the grain in a piece of timber. They show features perfectly earthlike and features so strange the Earth has no names for them. Theres a worlds worth of scientific puzzles here, some of them already tentatively answered, most still mysterious. Theres a worlds worth of possibilities. But theres no clear place to start the story.

If people had moved across the pinkish ochreif they had grown vines on the terraces of Olympus, or herded goats through the Labyrinths of the Night; if legends haunted Tempe and the dales of Arcadia, or if in Ares Vallis ancient grudge had broken into new mutinythen it would be easy. But there are none of those tales to tell. No gardens of Eden, no sacred springs, nowhere to start the story of a world.

Even stripped of people, with their cities and their borders and their histories, a map of Earth would not be this unyielding. Global truths and discrete units of geography would draw the eye. River catchments would tile the plains, mountain ranges would stand like the backbones of continents. There would be seas and islands, well defined. But Mars is not like that. It is continuous, seamless and sealess. Its great mountains stand alone; there are no sweeping ranges, no Rockies or Alps or Andes. The rivers are long gone. There are no continents and there are no oceans, and thus there are no shores. Given patience, provisions, and a pressure suit you could walk from any point on the planet to any other. No edges guide the eye or frame the scene. Nowhere says: Start Here.

We might begin the story at one of the places that humanity has touched. In 1971 a Russian spacecraft crashed near Hellas, a vast basin in the southern hemisphere, while another landed more decorously on the other side of the planet, somewhere in or around the crater Ptolemaus. Two years later another Russian probe struck the surface somewhere near the dry valley called Samara. None sent back anything by way of a message. In 1976 Americas more sophisticated Viking landers lowered themselves gently to sites in the northern plains of Chryse and Utopia, sending back panoramas of rock and rubble beneath pink-looking skies. But the Vikings eventually fell silent too, leaving Mars alone again. Preludes, not beginnings.

Twenty years later, the National Aeronautics and Space Administrations (NASA) little Pathfinder, cocooned in airbags, bounced to a halt in the rocky fields where Ares Vallis had once spewed out its floodwaters. It let loose Sojourner, the first of humanitys creations to travel on its own across the sands of Mars. That was a new beginning, the beginning of a grand age for Earths robots. At the time of writing there have been automatic envoys sending data back from Mars ever since. But Pathfinders story cannot encompass the whole vast world in front of me. Not yet.

What about beginning on Earth? Some places here are very like locations there, perhaps close enough to be tied together by some sort of sympathetic story-magic. Maybe Antarctica, where the driest, coldest landscapes on Earth are regularly visited by scientists wanting to get some sense of a smaller, drier, colder world. Or Iceland, where permafrost and lava fight as once they did on Mars. Or the scablands of Washington State, ripped clean by floods like those that scoured Pathfinders landing site. Or Hawaiis volcanoes, near-perfect miniatures of the Martian giants. Or Arizonas Meteor Crater, where earthly geologists first came to grips with what a little bit of asteroid can do to the face of a planet, given enough speed. They are all places where one can learn about Mars, where the trained imagination can almost touch it. But none evokes the whole world.

We could cast our imaginations wider, to those who have tried to speak for all of Mars. To the astronomers looking at it with their telescopes, measuring all the qualities of light reflected from its surface, seeing seasons and imagining civilizations. Or to the writers inspired by those astronomical visions: H. G. Wells and Stanley Weinbaum, Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury and Alexander Bogdanov and Edgar Rice Burroughs. Their imaginations took a point of light and turned it into a world of experience. But their Mars was never this one, the one that we only sawthat we could only ever seeafter our envoys left the Earth and went there.

Only after our spacecraft reached its orbit could we see Mars for what it is, a planet with a surface area as great as that of the Earths continents, all of it as measurable, as real as the stones in the pavement outside your door. After millennia of talking about worlds beyond our own, of heavens and hells and the Isles of the Hesperides, humanity now has such a world fixed in its sights, solid and sure. For the moment it is a world of science, untouchable but inspectable and oddly accessible, if only through the most complex of tools. But unlike the other worlds that scientists create with their imaginations and instrumentsthe worlds of molecular dynamics and of inflationary cosmology and all the rest of themthis one is on the edge of being a world in the oldest, truest, sense. A world of places and views, a world that would graze your knees if you fell on it, a world with winds and sunsets and the palest of moonlight. Almost a world like ours, except for the emptiness.

Next page