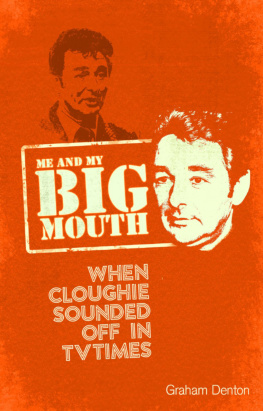

I should like to thank the following for their help and patience: Barbara, Jo Sadler, Wendy Lawrence, Colin Lawrence, Ron Fenton, Adam Sisman and Gerald Mortimer.

They are all good friends. Most of all I should like to acknowledge the help of John Sadler, without whom this book could not have been written.

1

THE MANGLE

I'm a bighead, not a figurehead.

If ever I'm feeling a bit uppity, whenever I get on my high horse, I go and take another look at my dear Mam's mangle that has pride of place in the dining-room at my home in Quarndon.

It had stood for a dozen years or so in our Joe's garage before being beautifully restored. Now it serves as a reminder of the days when I learned what life was all about. On top of it is the casket holding the scroll to my Freedom of the City of Nottingham. My whole life is there in one small part of one room.

The mangle has the greatest significance. It is the symbol of my beginnings. I spent my formative years mangling the sheets for my Mam, Sarah. My wife, Barbara, berates me to this day because she believes I wasted my education. I never managed to progress further than a secondary-modern school, no O levels, no A levels, but that mangle taught me more than any teacher in any classroom.

My values stemmed from the family. Anything I have achieved in life has been rooted in my upbringing. Some might have thought No. 11 Valley Road, Middlesbrough, the end of the terrace, was just another council house, but to me it was heaven. Growing up in a hard-working, often hard-up home I was as happy as a pig in the proverbial. I absolutely adored that red-brick house, with its lovely wooden gate and the garden round the side where Dad grew his rhubarb and his sprouts. Council houses had big rooms in those days, so we didn't live like sardines even though we slept three to a bed.

The first memory I have is of running down the alley for my dinner. Now we call it lunch, but it was dinner to us then. I can still recall the lovely, welcoming smell that greeted me as I skipped round the corner.

Mam had eight of us to feed, eight pairs of shoes to clean every night. Joe, my eldest brother, was head of the family, as he still is today. After him came sister Doreen, brothers Des and Bill, me, Gerald, little sister Deanna, and Barry. Another sister, Betty, had died before I arrived. I was born on the first day of spring, 21 March 1935.

Dad, Joseph, seemed to work all the hours God sent. A sugar boiler originally and then manager at Garnett's sweet factory, near Middlesbrough's football ground, Ayresome Park, Dad was obsessed with football and footballers. The great Middlesbrough players of the time, men like Wilf Mannion and George Hardwick, would go to the factory and Dad would give them sweets. Nowadays footballers get cars and too much money. The pendulum has swung the other way and swung too far.

We didn't see that much of Dad. He was off to work by seven-thirty and not home until six or so. But Mam was always there. She ran the house, as most women did in those days. She made my childhood warm and cosy and safe the most precious gift parents can give their offspring. The smell of liver and onions and the thought of dumplings, always crispy, and then her own rice pudding with nutmeg on the top to follow ...

Dinner was always on the table and we had to be there to eat it. On time, on the dot. It was the equivalent of a crime to let the dinner go cold. She put it down, piping hot, always with the warning, 'Eat it from around the edges where it's cooler.' I've never forgotten that.

Afterwards there would be Mam's rice pudding, made with Carnation milk. Everything we did, the way we lived, the way the house was run, was controlled by Mam, because she was the one who did the work and the organising. When I look back now to those early days of sheer contentment one factor stands out above all others. My mother was there. All the time, when we got out of bed in the mornings, raced home from school for dinner, again in the afternoon and after playing cricket or football on Clairville Common or Albert Park, she was there.

It's not the fashion to say this nowadays, but a woman's job is to be there. If she is going to have children, she has to look after them. It is not the only part of her job, but it is the most important part. Women who choose to stay at home and raise their families make one of the most valuable contributions to society as far as I am concerned. It is a source of intense annoyance to me when people talk of such women as 'only' housewives. As if it is not a proper job when in reality it is the toughest and most worthwhile job of all. To come home to an empty house must be petrifying for a small child. I remain certain that the character and disposition of children is established during those formative years. Women today have broader interests and involvements, but I will always be grateful for the security and peace of mind the Clough clan gained from Mam always being there and making our home the best place to be.