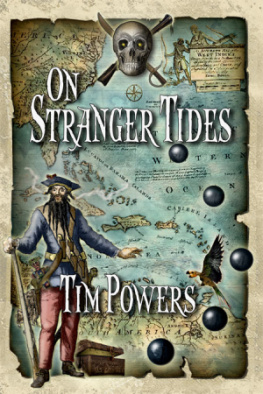

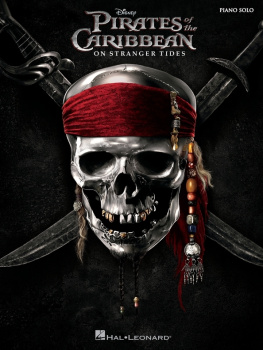

ON STRANGER TIDES

Tim Powers

To Jim and Viki Blaylock most generous and loyal of friends and to the memories of Eric Batsford and Noel Powers.

With thanks to David Carpenter, Bruce Oliver, Randal Robb, John Swartzel, Phillip Thibodeau and Dennis Tupper, for clear answers to unclear questions.

And unmoor'd souls may drift on stranger tides

Than those men know of, and be overthrown

By winds that would not even stir a hair

William Ashbless

"The Bridegroom's doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin;

The guests are met, the feast is set:

May'st hear the merry din."

He holds him with his skinny hand,

"There was a ship," quoth he

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Prologue

Though the evening breeze had chilled his back on the way across, it hadn't yet begun its nightly job of sweeping out from among the island's clustered vines and palm boles the humid air that the day had left behind, and Benjamin Hurwood's face was gleaming with sweat before the black man had led him even a dozen yards into the jungle. Hurwood hefted the machete that he gripped in his leftand onlyhand, and peered uneasily into the darkness that seemed to crowd up behind the torchlit vegetation around them and overhead, for the stories he'd heard of cannibals and giant snakes seemed entirely plausible now, and it was difficult, despite recent experiences, to rely for safety on the collection of ox-tails and cloth bags and little statues that dangled from the other man's belt. In this primeval rain forest it didn't help to think of them as gardes and arrets and drogues rather than fetishes, or of his companion as a bocor rather than a witch doctor or shaman.

The black man gestured with the torch and looked back at him. "Left now," he said carefully in English, and then added rapidly in one of the debased French dialects of Haiti, "and step carefullylittle streams have undercut the path in many places."

"Walk more slowly, then, so I can see where you put your feet," replied Hurwood irritably in his fluent textbook French. He wondered how badly his hitherto perfect accent had suffered from the past month's exposure to so many odd variations of the language.

The path became steeper, and soon he had to sheathe his machete in order to have his hand free to grab branches and pull himself along, and for a while his heart was pounding so alarmingly that he thought it would burst, despite the protective drogue the black man had given himthen they had got above the level of the surrounding jungle and the sea breeze found them and he called to his companion to stop so that he could catch his breath in the fresh air and enjoy the coolness of it in his sopping white hair and damp shirt.

The breeze clattered and rustled in the palm branches below, and through a gap in the sparser trunks around him he could see watera moonlight-speckled segment of the Tongue of the Ocean, across which the two of them had sailed from New Providence Island that afternoon. He remembered noticing the prominence they now stood on, and wondering about it, as he'd struggled to keep the sheet trimmed to his bad-tempered guide's satisfaction.

Andros Island it was called on the maps, but the people he'd been associating with lately generally called it Isle de Loas Bossals, which, he'd gathered, meant Island of Untamed (or, perhaps more closely, Evil) Ghosts (or, it sometimes seemed, Gods). Privately he thought of it as Persephone's shore, where he hoped to find, at long last, at least a window into the house of Hades.

He heard a gurgling behind him and turned in time to see his guide recorking one of the bottles. Sharp on the fresh air he could smell the rum. "Damn it," Hurwood snapped, "that's for the ghosts."

The bocor shrugged. "Brought too much," he explained. "Too much, too many come."

The one-armed man didn't answer, but wished once again that he knew enoughinstead of just nearly enoughto do this alone.

"Nigh there now," said the bocor, tucking the bottle back into the leather bag slung from his shoulder.

They resumed their steady pace along the damp earth path, but Hurwood sensed a difference nowattention was being paid to them.

The black man sensed it too, and grinned back over his shoulder, exposing gums nearly as white as his teeth. "They smell the rum," he said.

"Are you sure it's not just those poor Indians?"

The man in front answered without looking back. "They still sleep. That's the loas you feel watching us."

Though he knew there could be nothing out of the ordinary to see yet, the one-armed man glanced around, and it occurred to him for the first time that this really wasn't so incongruous a settingthese palm trees and this sea breeze probably didn't differ very much from what might be found in the Mediterranean, and this Caribbean island might be very like the island where, thousands of years ago, Odysseus performed almost exactly the same procedure they intended to perform tonight.

It was only after they reached the clearing at the top of the hill that Hurwood realized he'd all along been dreading it. There was nothing overtly sinister about the scenea cleared patch of flattened dirt with a hut off to one side and, in the middle of the clearing, four poles holding up a small thatched roof over a wooden boxbut Hurwood knew that there were two drugged Arawak Indians in the hut, and an oilcloth-lined six-foot trench on the far side of the little shelter.

The black man crossed to the sheltered boxthe trone, or altarand very carefully detached a few of the little statues from his belt and set them on it. He bowed, backed away, then straightened and turned to the other man, who had followed him to the center of the clearing. "You know what's next?" the black man asked.

Hurwood knew this was a test. "Sprinkle the rum and flour around the trench," he said, trying to sound confident.

"No," said the bocor, "next. Before that." There was definite suspicion in his voice now.

"Oh, I know what you mean," said Hurwood, stalling for time as his mind raced. "I thought that went without saying." What on earth did the man mean? Had Odysseus done anything first? Nonothing that got recorded, anyway. But of course Odysseus had lived back when magic was easy and relatively uncorrupted. That must be ita protective procedure must be necessary now with such a conspicuous action, to keep at bay any monsters that might be drawn to the agitation. "You're referring to the shielding measures."

"Which consist of what?"

When strong magic still worked in the eastern hemisphere, what guards had been used? Pentagrams and circles. "The marks on the ground."

The black man nodded, mollified. "Yes. The verver." He carefully laid the torch on the ground and then fumbled in his pouch and came up with a little bag, from which he dug a pinch gray ash. "Flour of Guinee, we call this," he explained, then crouched and began sprinkling the stuff on the dirt in a complicated geometrical pattern.

The white man allowed himself to relax a little behind his confident pose. What a lot there was to learn from these people! Primitive they certainly were, but in touch with a living power that was just distorted history in more civilized regions.

"Here," said the bocor, unslinging his pouch and tossing it. "You can dispose of the flour and rum and there's candy in there, too. The loos are partial to a bit of a sweet."

Hurwood took the bag to the shallow trenchhis torch-cast shadow stretching ahead of him to the clustered leaves that walled the clearingand let it thump to the ground. He stooped to get the bottle of rum, uncorked it with his teeth and then straightened and walked slowly around the trench, splashing the aromatic liquor on the dirt. When he'd completed the circuit there was still a cupful left in the bottle, and he drank it before pitching the bottle away. There were also sacks of flour and candy balls in the bag, and he sprinkled these too around the trench, uncomfortably aware that his motions were like those of a sower irrigating and seeding a tract.