Text copyright 2010 by Ed Butts

Published in Canada by Tundra Books,

75 Sherbourne Street, Toronto, Ontario M 5 A 2 P 9

Published in the United States by Tundra Books of Northern New York,

P.O. Box 1030, Plattsburgh, New York 12901

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010928786

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Butts, Edward, 1951

Shipwrecks, monsters, and disasters

of the Great Lakes / Ed Butts.

eISBN: 978-1-77049-259-2

1. ShipwrecksGreat Lakes (North America)History.

2. Great Lakes (North America)History. I. Title.

G 525. B 877 2011 971.3 C 2010-903167-9

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

v3.1

For Kyle Howell of Cape Breton;

my cousin and a true authority on the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Authors Note

At the time of these events, imperial measurements were used in Canada as they still are in the United States today. To conform to the standards of the times, I have used imperial measurements. The following tables will help if you need a better understanding of distances, temperatures, and weights.

| 1 inch | = | 2.4 centimeters |

| 1 foot | = | 30.48 centimeters |

| 1 yard | = | .91 meters |

| 1 mile | = | 1.60 kilometers |

| 32 degrees Fahrenheit | = | 0.00 degrees Celsius |

| 100 degrees Fahrenheit | = | 37.77 degrees Celsius |

| 1 ton | = | 1.10 metric tonnes |

Contents

Introduction

I n 1679, a French ship called the Griffon, the first sailing vessel built on the Great Lakes, left Green Bay on Lake Michigan, bound for Niagara with a cargo of furs. The Griffon and the five-man crew were never seen again. Though no one knows exactly what happened to the ship, there is no doubt that the Griffons mysterious disappearance was the result of the first shipwreck on the Great Lakes.

Since the loss of the Griffon, more than six thousand vessels, large and small, have met tragic ends on the Great Lakes. The bottoms of Lakes Ontario, Erie, Huron, Michigan, and Superior are littered with their wreckage and the bones of the people who sailed on them. Their stories live on in songs and legends that make up the lore of the lakes.

Before railroads and highways were built, the Great Lakes were the principal means of transportation into the heart of North America. Freighters carried timber, grain, ore, livestock, and the products of industry. For hundreds of thousands of immigrants, the Great Lakes were a major leg on their journey west. As commercial traffic grew, small ports became major cities: Toronto, Buffalo, and Chicago, to name a few. People traveling from one Great Lake community to another usually went by boat. Even after the coming of the railroads and highways, shipping remained the cheapest way to transport goods. This was especially true after the St. Lawrence Seaway opened the Great Lakes to ocean-going vessels.

For many years salt-water mariners scoffed at the fresh-water sailors of the Great Lakes. They said the lakes were mere puddles compared to the vast oceans, and were no challenge to real seamen. Sailors who had actually worked on the lakes knew differently.

Even in the best sailing conditions, the skippers of Great Lakes vessels worried about shoals and reefs uncharted rocks and sandbars that could snare a ship or rip a hull wide open. Unpredictable winds could capsize a vessel in a moment. A ship caught in a storm on the lakes did not have as much room to maneuver as did a ship at sea. Rocky shorelines awaited in every direction. One veteran Atlantic sea captain who had looked down on Great Lakes sailors, said that he had gained a new respect for them after just one rough day on windy Lake Ontario.

Storms that blew in without warning, fog that hung over the water like a thick blanket, and ice that could grind wooden hulls to splinters were the natural perils. But Great Lakes sailors were also endangered by human folly. Ship owners and corporate bosses often placed profit ahead of everything, including the safety of crews and passengers. It wasnt uncommon for captains to sail in dangerous weather against their better judgment because greedy employers did not want to lose money while ships sat in port. This was especially true when the navigation season was nearing its end in stormy November, and captains were pressured into making one more run before shipping shut down for the winter. Many vessels lacked safety and emergency equipment because their owners did not want to buy it. Passenger ships were frequently overcrowded when travel companies tried to wring every possible dollar out of a voyage. If a ship did sink, the owners claimed insurance.

Eventually the lakes were completely mapped and charted, and markers and lighthouses warned captains of dangerous rocks and shoals. Technology improved weather-warning systems, and better ship-to-shore communications helped avoid disasters. Seamens unions fought for improvements in safety, and governments passed laws that prevented some of the worst shipping companies abuses. But even with all these advances, in many aspects the Great Lakes remain untamed, and any ship venturing out of port into the wilderness of water faces the unexpected.

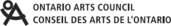

Foredoomed is a word seldom used these days. It conjures up images of a bygone era. However, since the events of this story took place in the early nineteenth century, perhaps it is appropriate to say that the crew of HMS Speedy, and all of the people associated with the murder trial of a Native named Ogetonicut were foredoomed. Some accounts say the Speedy was unseaworthy. That may have been so. As wooden ships of the time went, she was old, having plied the waters of Lake Ontario for twenty-seven years. It has also been said that had there been a lighthouse on the Presquile Peninsula, the Speedy might have reached port safely.

But if the people of the Speedy were indeed foredoomed, maybe the friendly beacon of a lighthouse would have made no difference.

The sequence of events that led to the disaster began a year earlier, when Whistling Duck, a member of the Muskrat branch of the Chippewas, was murdered near Lake Scugog, in what was then called Upper Canada. Whistling Ducks brother, Ogetonicut, accused a white man named John Sharp of the crime. Sharp, formerly a soldier with the Queens Rangers, was the manager of Farewells trading post at Bull Point on Lake Skugog. Colonial authorities promised Ogetonicut that his brothers slayer would be punished. Had that promise been kept, the