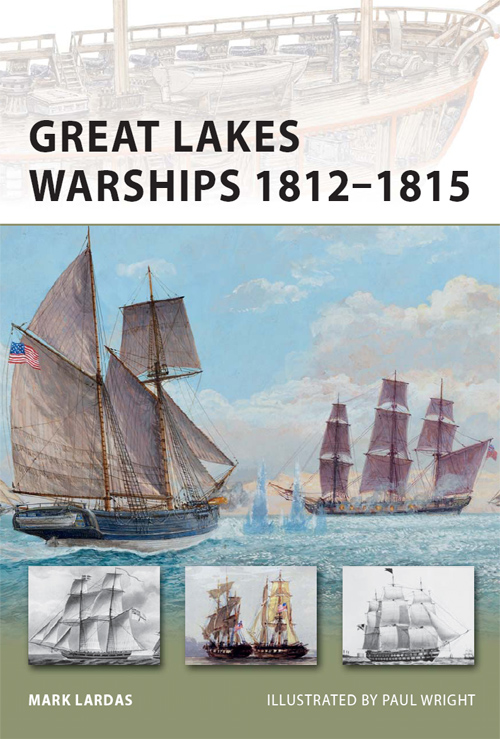

NEW VANGUARD 188

GREAT LAKES WARSHIPS 18121815

| MARK LARDAS | ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT |

CONTENTS

GREAT LAKES WARSHIPS 18121815

INTRODUCTION

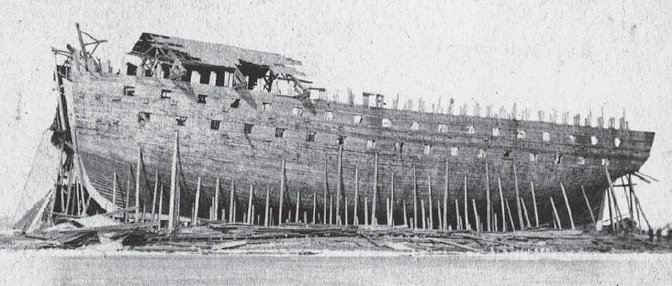

The hull of the New Orleans was a gaunt silhouette etched against the skyline. It had never been launched, and was still cradled on its building ways. Yet it was a ruin. That was unsurprising the hull was nearly 70 years old. It had been constructed in the winter months of 1814 and 1815, and left incomplete. No further work was done, except to roof the hull over in an effort to preserve the ship for future use.

That need never came. By 1883, the ship was an anachronism. New Orleans was, as a ship-of-the-line, the class of warship that had decided the Battle of Trafalgar almost 80 years earlier. But New Orleans stood far from the saltwater oceans that were the normal habitat of that species. Rather, its building ways were on the shore of Lake Ontario, a freshwater sea 150 miles from the nearest ocean.

Sea is the right word to describe Lake Ontario. Lake implies a smaller body of water, something that one could canoe across, and primarily useful for recreation. Yet Ontario, along with sister lakes Erie, Huron, Michigan, and Superior, were on a far larger scale, tens of thousands of square miles in area and hundreds of miles in length and width. Carved out by glaciers, the Great Lakes, along with their tributaries and a few smaller lakes, such as Lake Champlain downstream of Lake Ontario, formed part of the St Lawrence Watershed.

New Orleans was the largest ship in the US Navy when its construction began in 1814. Work on the ship-of-the-line ceased after peace in 1815. It remained incomplete on its building ways for nearly 70 years, before being disassembled in 1883. (USNH&HC)

From the 1600s until the early 1800s, when the American railroad finally appeared, this waterway offered a highway into the heart of the North American continent, one along which goods and people could move. Movement was not effortless. Shallows, rapids, and falls interrupted free passage by water, requiring portaging. But those sections were typically short, and the size of the lakes offered unparalleled access to the continental interior. The lakes were so large that, except at choke points like the St Clair River linking Lakes Huron and Erie, access could not be dominated by shore batteries, certainly not by smoothbore artillery, whose 3-mile maximum range led to the initial definition of territorial waters. Even Lake Champlain, a 125-mile long slot, was 14 miles across at its widest point.

To control such sizable lakes and to ship goods across them required big ships, as large as the unfinished and now-useless ship-of-the-line on the banks of Lake Ontario. The Navy would sell its hulk and have it dismantled later that year. Yet for a brief three years, ships similar to it clashed on these waters in an effort to dominate them.

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

The Great Lakes offered naval architects unique advantages and challenges. For a start, the lakes are freshwater bodies. Freshwater has distinct maritime benefits. Ships on freshwater lakes need only a days worth of drinking water a bucket over the side allowed the supply to be refreshed. In the early 1800s, as long as you took the water from the lake itself, not from a harbor where ships moored, it was safe to drink. As late as the 1970s, freighters drew drinking water, untreated, from Lake Superior. Lacking the necessity to store large quantities of barreled drinking water, storage requirements were reduced.

The St Lawrence Watershed, which included the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, was the thoroughfare into the North American interior in 1812. (LOC)

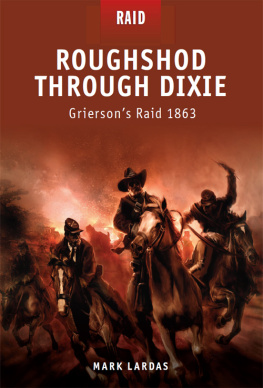

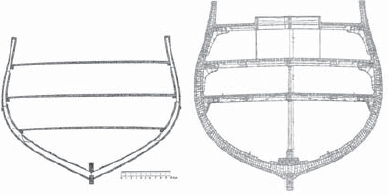

The difference in fullness and deadrise of ocean-going and lakes warships can be seen in this comparison between the cross-section of frigates Princess Charlotte (left) and Constitution (right). (Princess Charlotte line reprinted courtesy of Daniel Walker, Constitution, USN)

Freshwater also kills teredo worms shipworms which bored through the wooden hulls of ocean-going ships. Such vessels were protected from shipworm by lining the underwater hull with copper plates, but copper-bottoming a ship was expensive, and unnecessary on the lakes. Seawater is also 3 percent denser than freshwater. A ship drawing 12ft of water off Cape Cod had a draft of 12ft 4in on Lake Ontario.

On the debit side, lakes warships faced greater challenges in terms of stability. Stability is a function of a ships center of gravity the higher the center of gravity, the less stable a ship becomes. Ninteenth-century ocean-going vessels had low centers of gravity by virtue of copper plating on the bottom of the hull, plus the storage of large amounts of food and water in the lower hold. A lakes warship did not require the copper plating, nor the extensive stores of food and water (the ships were never more than two days from port), but without them the ships center of gravity was much higher. Placing heavy guns on a ships deck or even adding solid bulwarks exacerbated the problem.

The stability problem was further exacerbated because of a desire for speed. While the lakes were big, virtually any destination within one lake could be reached in a couple of days, even sailing at 5mph (4.3 knots). (Statute miles were customarily used by lakes mariners.) But ships with a good turn of speed, say 13mph (12 knots) could complete a typical voyage between sunrise and sunset, thereby simplifying watch-keeping and reducing the need for crew accommodations while increasing cargo space.

Speed was achieved by building hulls with high deadrise. Deadrise is the angle of the hull measured from the keel to its widest beam. Flat-bottomed hulls have no deadrise, whereas V-shaped hulls have high deadrise. All other factors being equal in two hulls of the same volume, the hull with the higher deadrise will be faster. High deadrise reduces the volume in the lower part of the hull. This reduces the fullness of the hull, and raises the center of gravity. Sailing ships with low deadrise had greater endurance than ships with high deadrise. They could also carry more stores, limiting the deadrise on ocean-going vessels. But endurance was less important than speed on the lakes, so shipwrights used higher deadrise further raising the center of gravity.

Modern replicas of HMS Tecumseth (left) and HMS Bee (right), schooners built for the Royal Navy on Lake Huron in 1816. Tecumseth, a warship, and Bee a transport, are representative of the vessels used on the upper lakes by the British. (Photo courtesy of Discovery Harbour, Penetanguishene, Ontario, Canada. Web: www.discoveryharbour.on.ca)