Contents

INTRODUCTION

In his six-volume series The Second World War , Winston Churchill wrote, The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boa t peril.

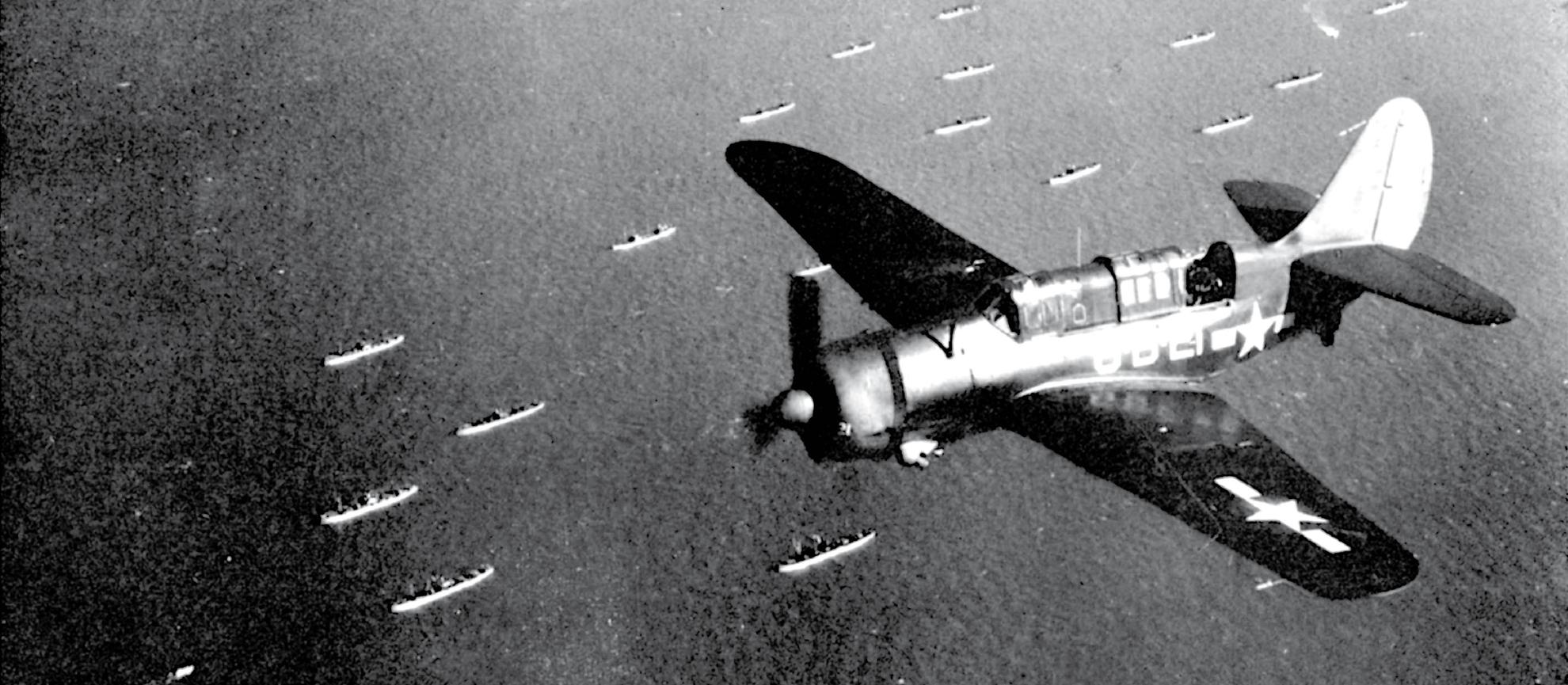

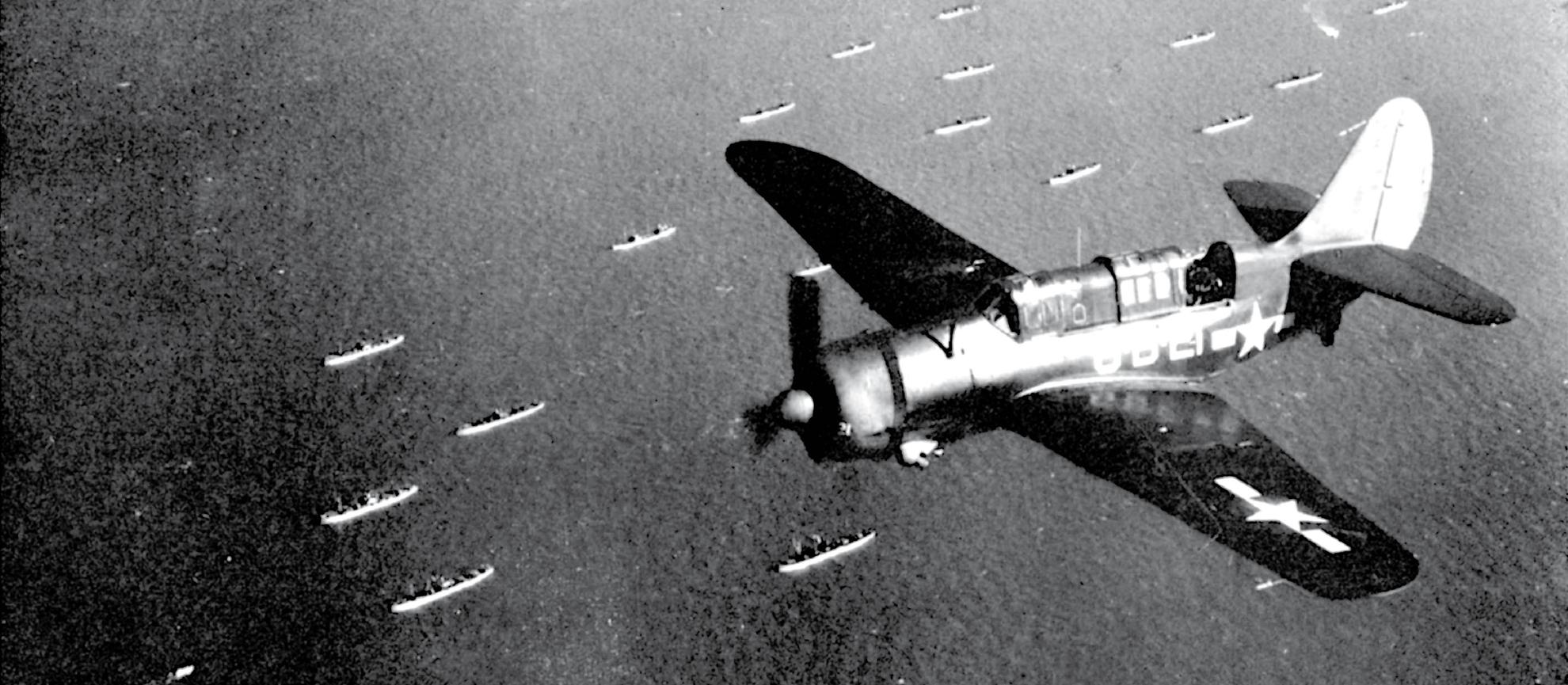

A Helldiver dive bomber guards a convoy off Norfolk, Virginia. While unsuitable for long-range convoy support, single-engine carrier aircraft operating from land bases could protect convoys as they formed or dispersed outside ports. (AC)

By the start of 1942, two things were obvious: the U-boat presented a deadly peril to Great Britains survival and Allied victory, and aircraft were the most effective tool for stopping U-boats. Both sides spent the first two years of the war squandering their advantages in the Battle of the Atlantic. Germany never built up U-boat numbers to decisive totals, while Britain neglected Coastal Command. Until January 1941 it lacked weapons capable of reliably sinking U-boats. Even after getting the weapons, aircraft inventories were kept at starvation levels and inadequate numbers were available for the tasks to be done. It was not that Britain lacked aircraft capable of maritime patrol, rather, those aircraft were assigned to other tasks, largely Bomber Command, not the maritime Coastal Command.

Yet as 1942 opened it seemed these problems were in the past, for bo th sides.

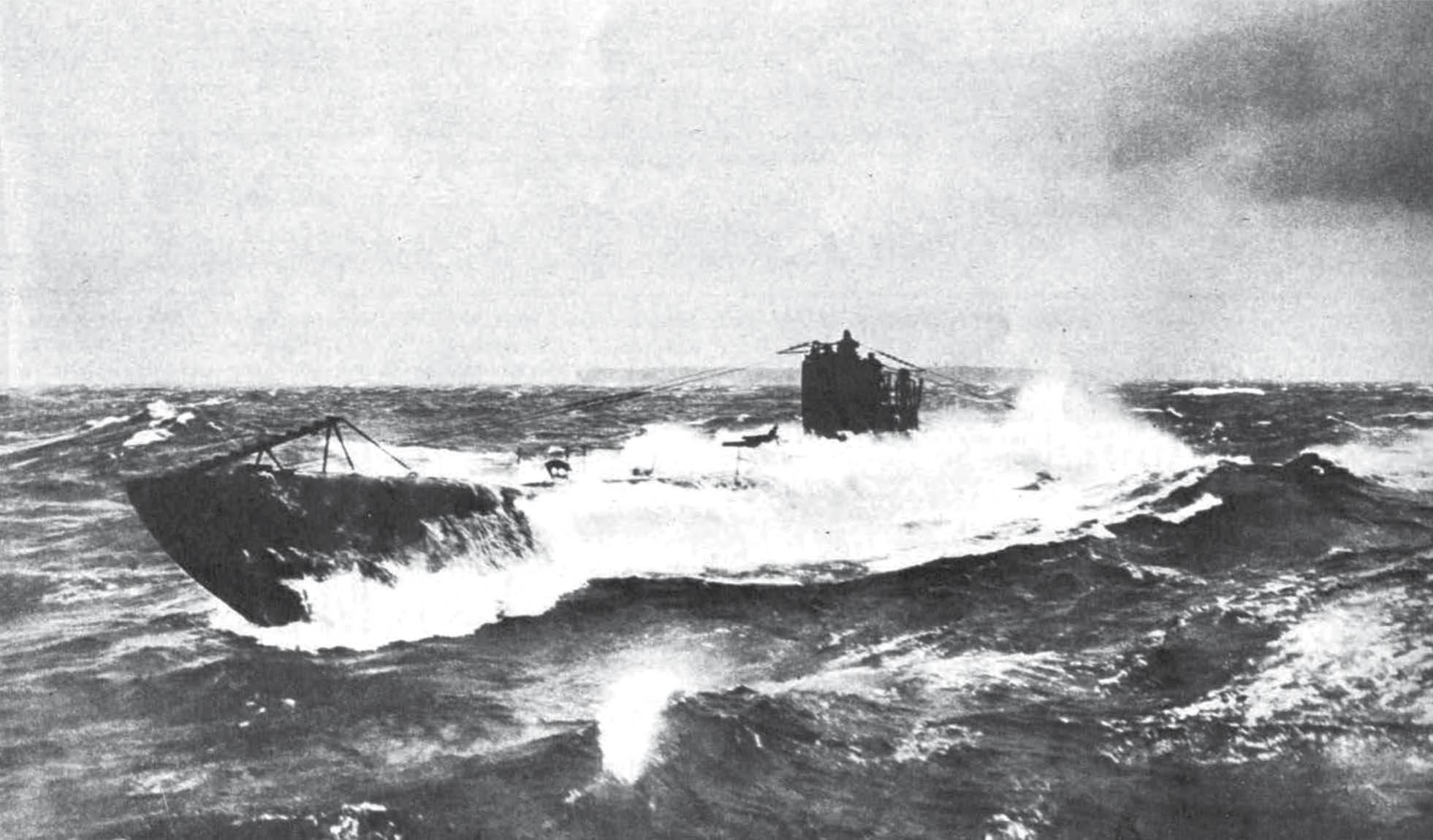

Germany had 91 operational U-boats, and over 150 in training or trials. Annual production for 194244 was planned to exceed 200 boats. In 1939 Karl Dnitz, running the Kriegsmarines U-boat arm, projected he needed 300 U-boats in commission to knock Britain out of the war. It looked like he would finally have the numbers needed to run the tonnage war he wanted against t he Allies.

Britain, though, had finally assembled the solution to the U-boat peril. Its weapons systems and detection systems had improved to the stage that maritime patrol aircraft could launch deadly attacks. In the closing days of December 1941, a Swordfish torpedo bomber, re-equipped for anti-submarine patrol, found a U-boat using radar, and sunk it at night. Darkness no longer shielded U-boats. Also in December, an escort carrier and very-long-range (VLR) aircraft from Ireland had prevented a U-boat pack and Luftwaffe Condors from savaging a homeward-bound convoy from Gibraltar. In a first in a protracted convoy battle, fewer Allied ships were sunk than U-boats.

Britain even gained a major ally: the United States, who entered the war following Japans attack on the US Navys base at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. By 11 December, a mutual exchange of declarations of war between Germany and the United States had drawn the Americans into the Battle of the Atlantic. The industrial might of the United States, larger than the combined economies of all of the other Allies or the combined economies of all Axis powers was to be brought to bear o n Germany.

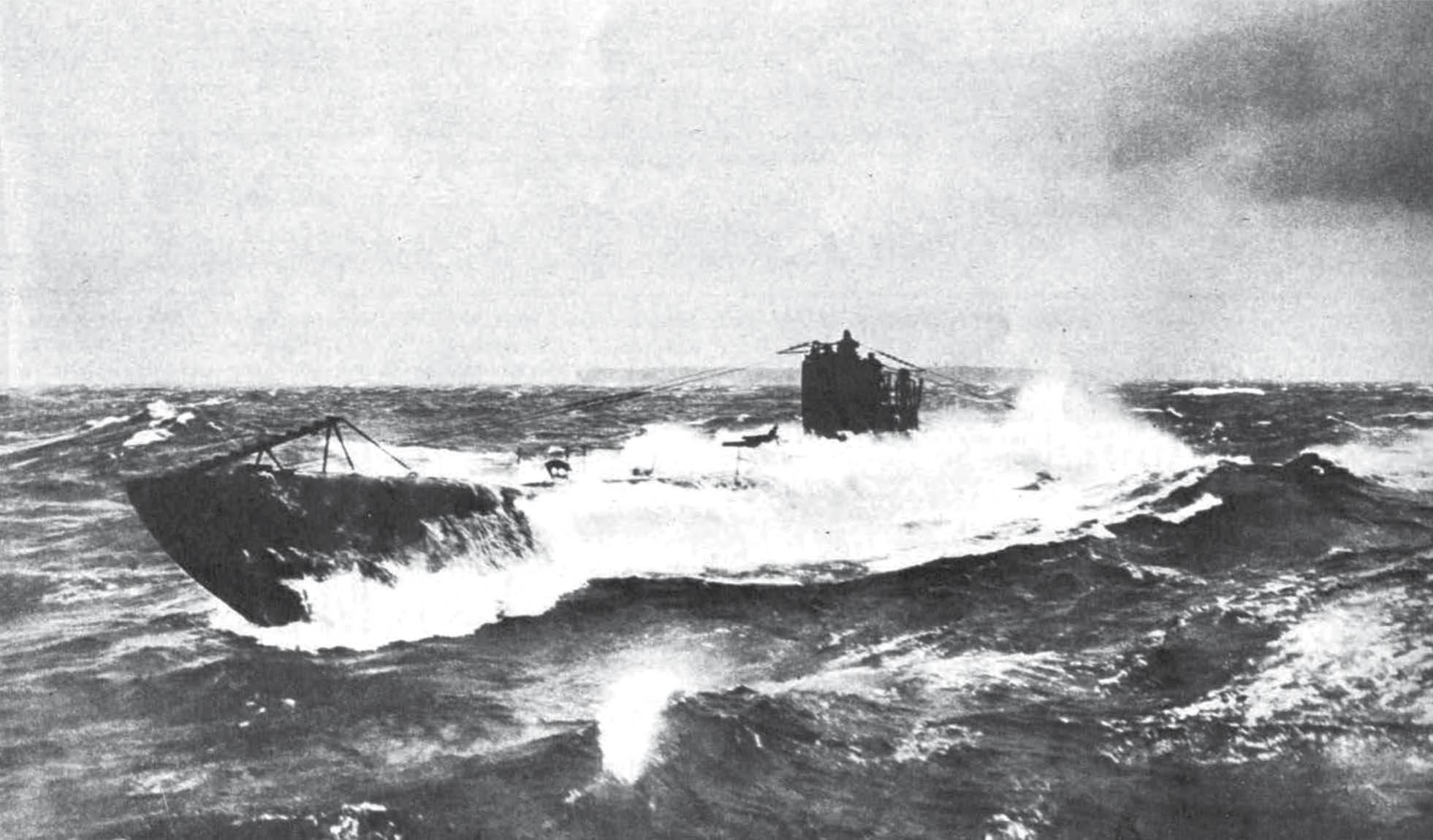

German U-boats threatened Britains connection with its supply lines. Their strength lay in finding weak spots in Allied anti-submarine defences, and attacking at those points. Anything unguarded was at risk to these sea wolves. (AC)

Unfortunately, the American entry into the war expanded the battlefield. The last time the battlefield expanded significantly, after France fell in the summer of 1940, the U-boats were able to flank the British. The first Happy Time resulted. U-boats tore into inadequately protected merchant vessels, both those in convoys and sailing independently. It took Britain nine months to end the U-boat rampage.

This time it would take longer to bring the situation under control. Hitler had kept Dnitz and his U-boats out of the western half of the Atlantic Ocean for fear of bringing the United States into alliance with Great Britain. With the US now allied with Britain, there was nothing to keep U-boats out of American waters, and almost nothing to stop them operating there.

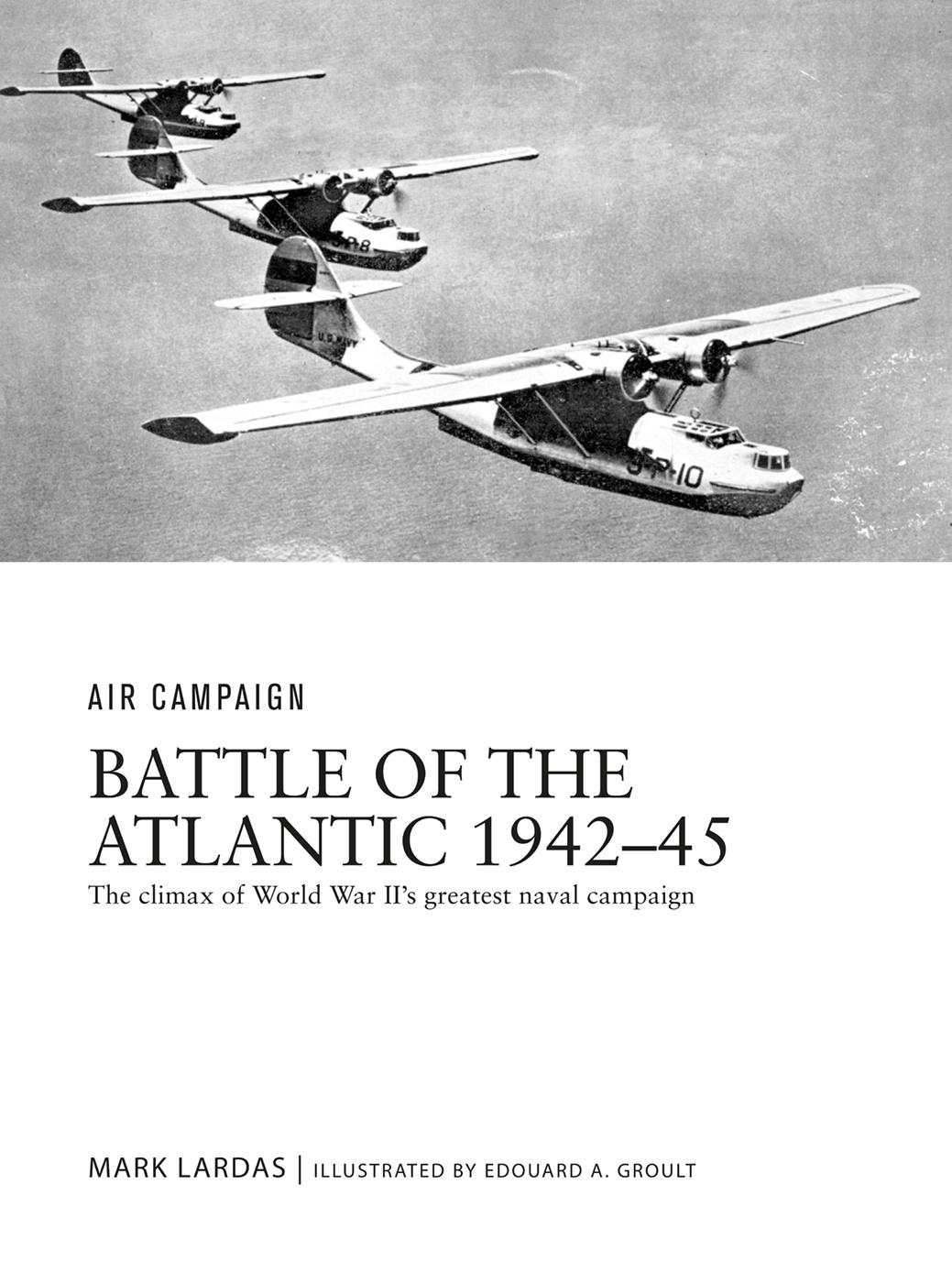

The United States was ill-prepared to counter the U-boat threat. There was no counterpart to Britains Coastal Command in either the United States Army or Navy. The Navy could use its long-range patrol squadrons for anti-submarine duties. These operated the long-range amphibian Catalina and Mariner flying boats, but most immediately available squadrons were already committed to stations in Iceland and Newfoundland. New squadrons had to be raised. The Army employed medium bomber squadrons on anti-submarine patrol, but the crews were untrained in attacking submarines.

Nor could the Navy immediately supply much in the way of surface escorts.