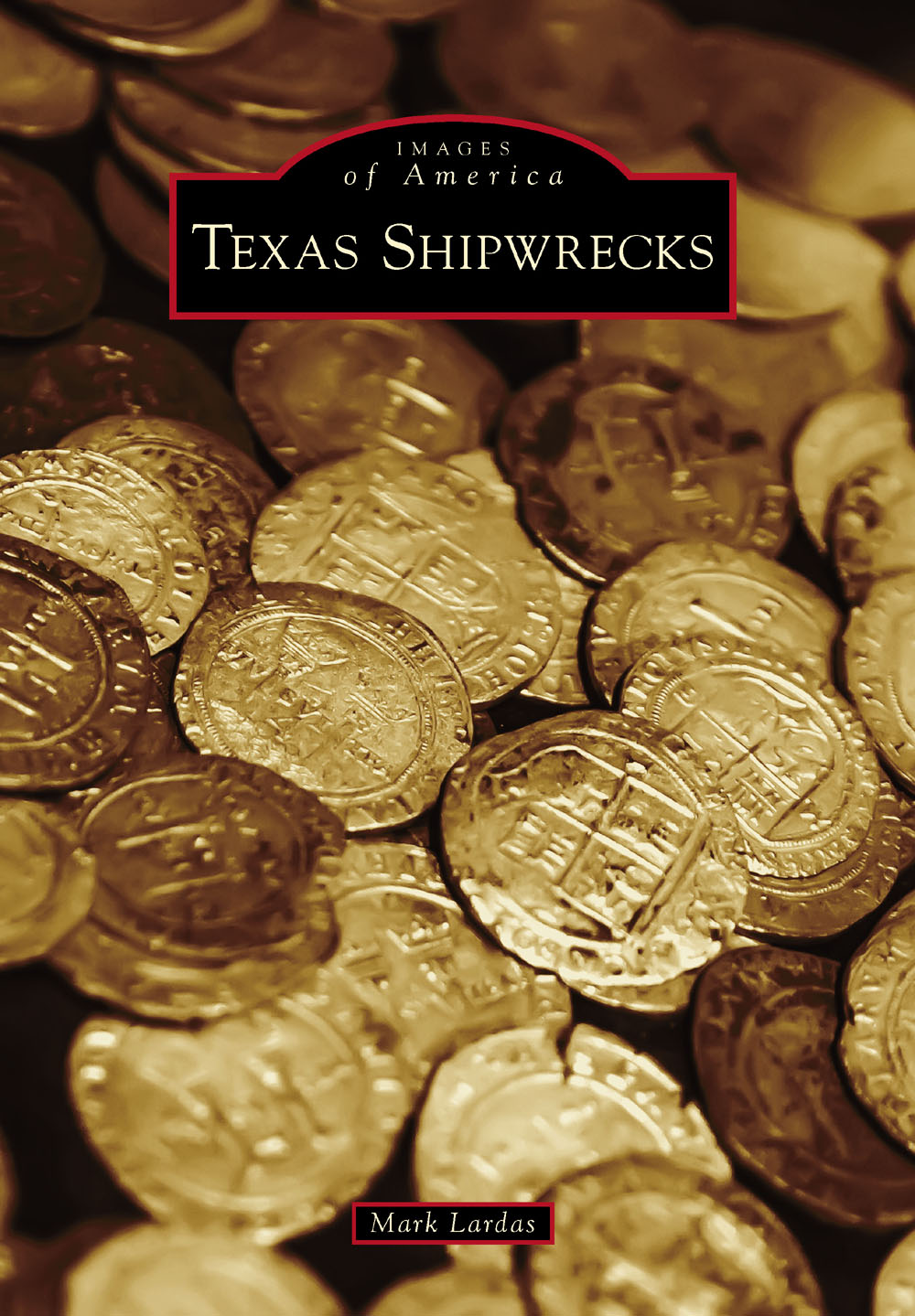

IMAGES

of America

TEXAS SHIPWRECKS

The Texas coastline and offshore waters are flat, shallow, featureless, and filled with shoals, as can be seen from this photograph of the Bolivar Peninsula on a hazy morning. Looking carefully, the Bolivar Lighthouse can be seen. The careless or unobservant can easily run aground, adding one more shipwreck to the Texas coast. (Authors collection.)

ON THE COVER: Pictured here are silver coins recovered from the 1554 wrecks, now on display at the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. (Photograph by William Lardas, from the Platoro, Keenon, Purvis Collection of the THC and the CCMS&H.)

IMAGES

of America

TEXAS SHIPWRECKS

Mark Lardas

Copyright 2016 by Mark Lardas

ISBN 978-1-4671-1617-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439655863

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015953581

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my mom, Betty Lardas, for everything.

I cannot believe it took me this long to dedicate one of my books to you.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

No book is the product of a single author. Many folks helped me as I wrote and assembled this book. Those I especially would like to note include my son, William Lardas, for accompanying me on many of my trips and doing the photography; Kevin Crisman, Glenn Greico, Donny Hamilton, and Justin Parkoff of Texas A&Ms Institute for Nautical Archeology; Chase Fountain, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department photographer; Peter DeForest and Henry Wolff Jr. for their help with Pass Cavallo wrecks; Andy Hall and Tom Oertling of Texas A&M Galveston; Teena Maenza and the other folks from the Columbia Museum; Lisa Meisch and the rest of the staff at the Sam Houston Regional Library and Research Center; Cheri Smith of the Jefferson Historical Museum; Linda Turner and Billie Powers of the Texas City Museum; Jonathan Plant, director of the John E. Conner Museum at TA&MU Kingsville; Amy Borgens and Brad Jones of the Texas Historical Commission; Jan Cocatre-Zilgien for his help with the Ferris ships; and Dan Warren, who provided imagery from his expeditions.

I would also like to thank Mike Kinsella and Matt Todd, my editors at Arcadia Publishing, for their assistance. As well, I thank my wife, Janet, for her support during this project.

The following abbreviations indicate the sources of the illustrations used in this volume:

| AC | Authors collection |

| BOEM | Bureau of Energy Management |

| CCMS&H | Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History |

| LOC | Library of Congress |

| NARA | National Archives |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| PKP | The Platoro, Keenon, Purvis Collection of the THC and the CCMS&H |

| SHRL&RC | Sam Houston Regional Library and Research Center |

| THC | Texas Historical Commission, Austin |

| TPWD | Texas Parks and Wildlife Department |

| UHDL | University of Houston Digital Archive Library |

| USACOE | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| USNH&HC | United States Navy Heritage and History Command |

| WL | Photograph by William Lardas |

INTRODUCTION

Shipwreck. The word evokes images of sunken Spanish treasure ships, their gold carpeting the sea bottom, or perhaps wreckers, deliberately luring ships aground in pursuit of salvage. The reality is less romantic, but often more interesting.

There are very few sunken treasure ships, mainly because only a small fraction of ships carried treasure, and most of those made it safely to port. (You cannot have a shipwreck unless a ship wrecks.) That is not to say it never happened. Three of the Texas shipwrecks discussed in this book were Spanish treasure ships. They were part of the annual silver flota sailing from Vera Cruz in Mexico to Havana, Cuba. But only those three.

Even ships that sank off Texas waters rumored to be carrying Army payrolls or bank transfers were not really treasure ships. The money might fill one strongbox. It was more often paper currency than specie. (Precious metal is heavy. Two cubic feet of gold12 inches by 12 inches by 24 inchesweighs over a ton. Even at its historic price of $20 an ounce between 1700 and 1930, that much gold is worth $700,000, the equivalent of $420 million todayliterally a kings ransom. It is easier to ship paper money.)

There are a lot of shipwrecks in Texas waters, though. The Texas coastline and offshore waters are flat, shallow, featureless, and filled with shoals. The navigable rivers (and Texas depended on river navigation in its early years), are narrow, twisting, and blanketed with sunken logs or sandbanks. Texass weather is equally unpredictable to mariners. It is not just hurricanes and tropical storms providing hazards; storm fronts known as Blue Northers can drop temperatures 40 degrees in a few hours. Equinoctial storms can push the water in or out of shallows, stranding vessels and wrecking them. Throw warfare into the mix, and you have a seashore and sea bottom peppered with wrecks.

These wrecks define Texas history. In fact, it can be said that Texass history started with a shipwreck. In 1528, while trying to sail to Mexico from Florida, Cabeza da Vaca was shipwrecked on Galveston Island. After eight years as a slave of local Indians and an epic hike to Santa Fe, New Mexico, he returned to Spain and wrote a book about his experiences. It was written historys first mention of what would become Texas.

Shipwrecks continued to play an important part in Texas history over the next six centuries. Sometimes shipwrecks played an obvious role. A major cause of the failure of La Salles attempt to create a French colony in Texas was the loss of two of the three ships of his expedition. First Amiable, and then la Belle, ran aground and sank. They took with them most of the expeditions supplies and trade goods and its only means of abandoning the colony. So, while La Salles colony gave Texas one of the six flags that flew over Texas, shipwrecks kept Texas from remaining a French possession.

Nearly two centuries later, Union attempts to capture key Confederate ports on the Texas coast were frustrated by its naval lossesand the ships sunkat the battles of Galveston and Sabine Pass. Instead, the North blockaded the Texas coast, leading to nearly three dozen Confederate blockade runners running aground or sinking off the coast.

Hurricanes cause shipwrecks as well. Some of Texass best known maritime figures, including pirates Luis Aury and Jean Lafitte, ran afoul of hurricanes. Plus, hurricanes generate dramatic photographs of ships stranded, sometimes miles inland. Yet Texass most dramatic shipwrecks were not caused by wind, water, or warfare. The Texas City Disaster, which sank three big freighters and a number of barges, was an industrial accident, an explosion caused by a fire aboard a freighter.

Yet most Texas shipwrecks occur without the glare of publicity or fame. A ship trying to negotiate a tricky channel runs aground. A river steamboat hits a snag, ripping its bottom open. Storm waves overwhelm a ship at sea, sending it anonymously to the bottom.

Next page