Copyright 2017 by Dan Egan

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Daniel Lagin

Production manager: Julia Druskin

JACKET DESIGN BY ERIC WHITE & FRANCINE KASS

JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY JUSTIN BECKMAN

ISBN: 978-0-393-24643-8

ISBN: 978-0-393-24644-5 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

In memory of Michael Faricy

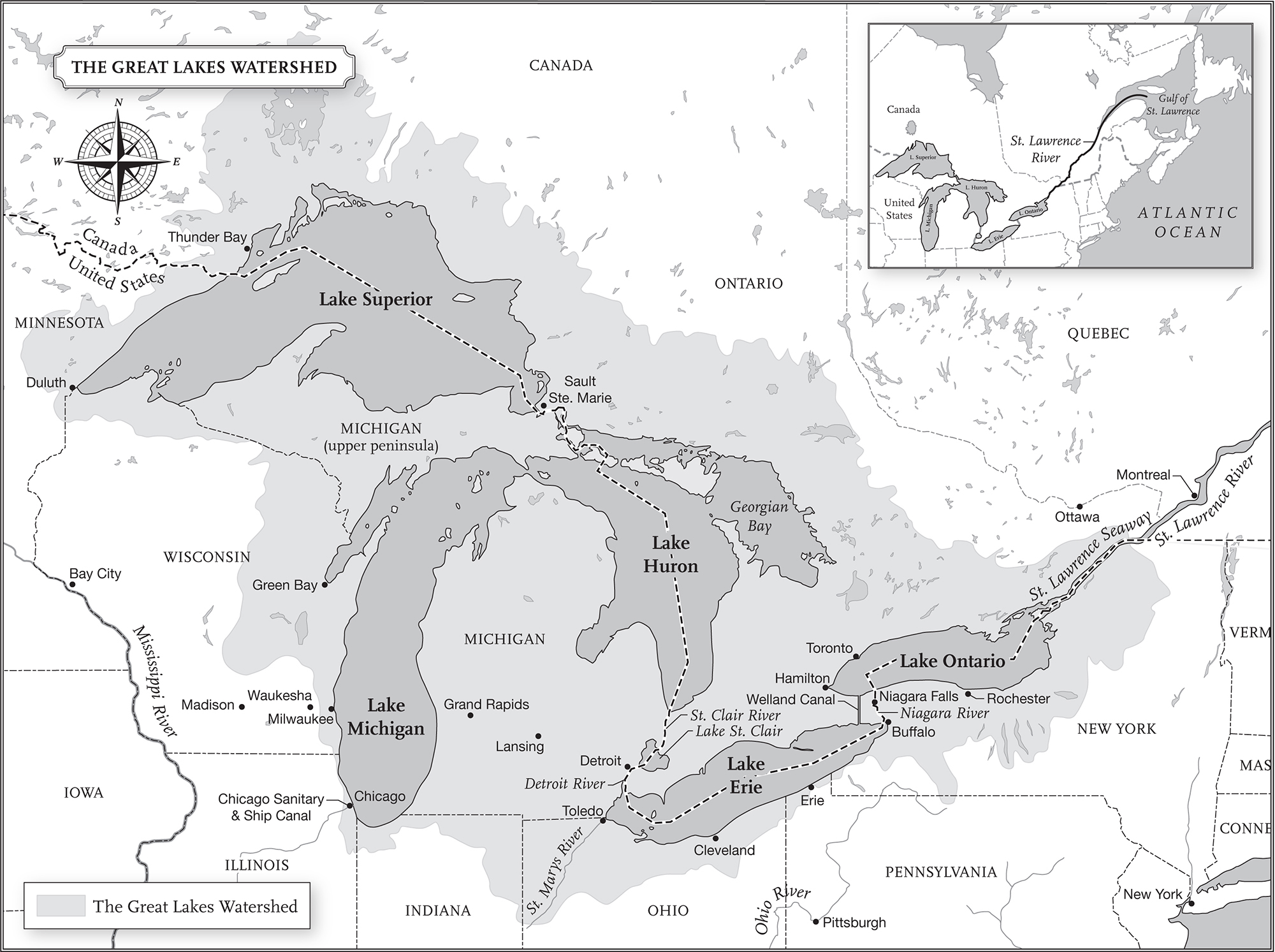

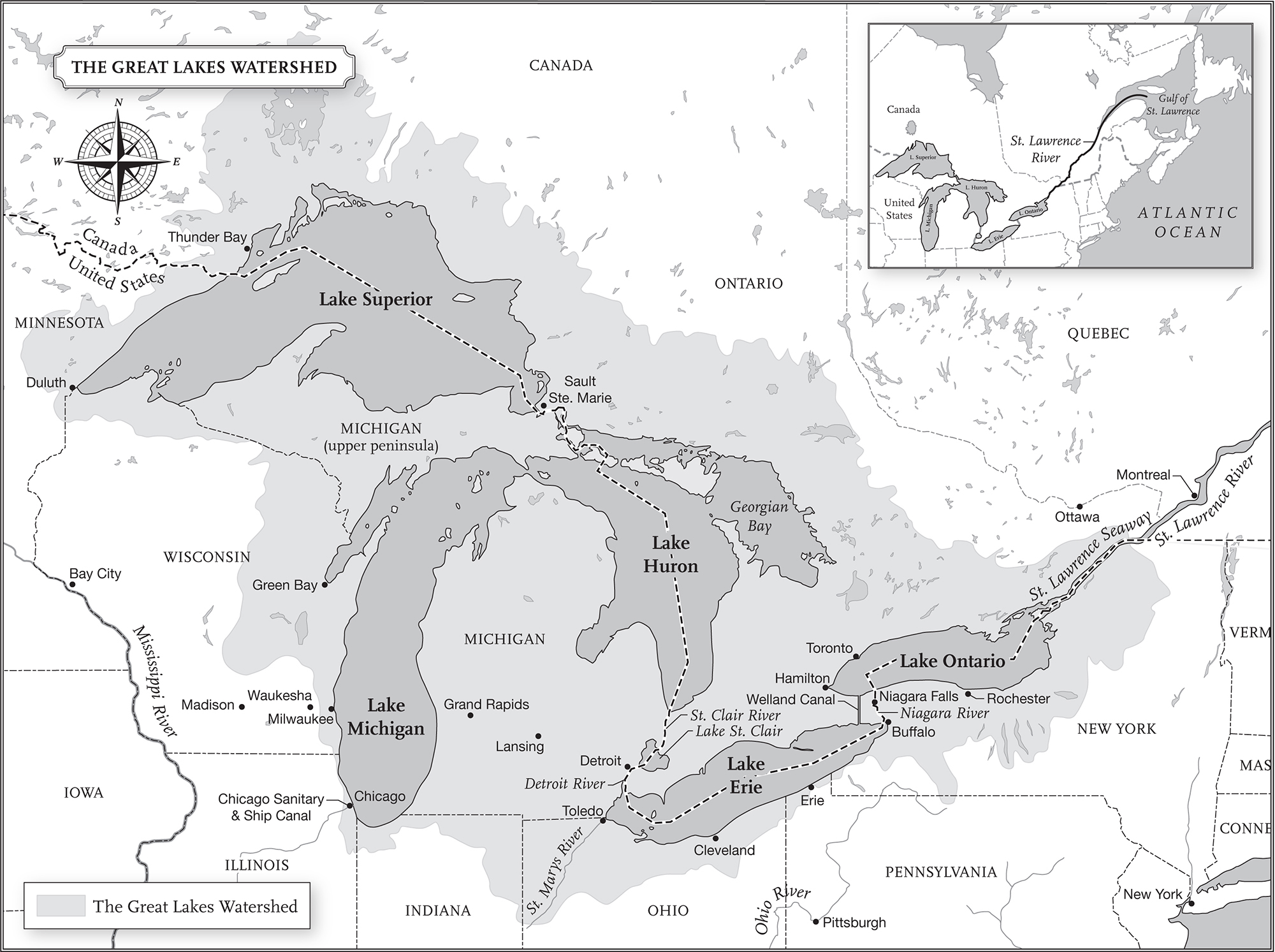

The Great Lakes watershed.

T here are few views that can draw noses to airplane windows like those of the Great Lakes. From on high, the five lakes that straddle the U.S. and Canadian border can appear impossibly blue, tantalizing as the Caribbean. Standing on their shores and staring out at their ocean-like horizons, it hits you that the Great Lakes are, in one significant way, superior to even the Seven Seas. The Great Lakes, after all, are so named not just for their size but for the fact that their shorelines cradle a global trove of the most coveted liquid of allfreshwater.

The worlds largest freshwater system has captured the publics imagination since the first European explorers arrived on the shores of the sweet water seas in the early 1600s convincedor at least ever-hopefulthat on their far shores lay the riches of China. In 1634 voyageur Jean Nicolet paddled his birch bark canoe across northern Lake Huron, through the Straits of Mackinac and headed for the western side of Lake Michigana place no white man had evidently ever set eyes upon. Nicolet arrived in a bay on the far shore of Lake Michigan apparently trying to look like a localin a flowing Chinese robe bursting with colorful flowers and birds. Although he might have thought he had finally finished the job Columbus started a century and a half earlier, he actually landed on the southern end of an arm of Lake Michigan known as Green Bay. There is a statue today of Nicolet in that robe that stands near the reputed landing site. Its 20 minutes north of Lambeau Field, some 7,000 miles shy of Shanghai.

Its hard to fault Nicolet if he really did believe his journey had taken him to Asia, because there were no Old World analogues for the scope of the lakes he was trying to navigate. The biggest lake in France, after all, is 11 miles long and about 2 miles wide; the sailing distance between Duluth, Minnesota, on the Great Lakes western end and Kingston, Ontario, on their eastern end is more than 1,100 miles. No, the bodies of water formally known as the Laurentian Great Lakes are not mere lakes, not in the normal sense of the word. Nobody staring across Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie or Superior would consider the interconnected watery expanse that sprawls across 94,000 square miles just a lake, any more than a visitor waking up in London is likely to think of himself as stranded on just an island (the United Kingdom, in fact, also happens to span some 94,000 square miles).

A normal lake sends ashore ripples and, occasionally, waves a foot or two high. A Great Lake wave can swell to a tsunami-like 25 feet. A normal lake, if things get really rough, might tip a boat. A Great Lake can swallow freighters almost three times the length of a football field; the lakes bottoms are littered with an estimated 6,000 shipwrecks, many of which have never been found. This would never happen on a normal lake, because a normal lake is knowable. A Great Lake can hold all the mysteries of an ocean, and then some.

In 1950, when Northwest Airlines flight 2501 flying from New York City to Seattle disappeared from radio contact after it hit a summer storm over Lake Michigan, it was at the time the worst commercial aviation accident in U.S. history. The Coast Guard and Navy dispatched five ships to look for the wreckage. They dropped sonar devices, divers and drag lines into the lake to hunt for the nearly 100-foot-long fuselage that carried 58 souls.

The wreck has never been found.

Here is a different way to grasp the scale of the Great Lakes. Roughly 97 percent of the globes water is saltwater. Of the 3 percent or so that is freshwater, most is locked up in the polar ice caps or trapped so far underground it is inaccessible. And of the sliver left over that exists as surface freshwater readily available for human use, about 20 percent of thatone out of every five gallons available on the planetcan be found in the Great Lakes. This is not an insignificant fact at a time when more than three-quarters of a billion people dont have regular access to safe drinking water.

In 1995, World Bank vice president Ismail Serageldin made a provocative prediction: The wars of this century have been fought over oil, and the wars of the next century will be on water... Perhaps. But the biggest enemy facing the Great Lakes in the early 21st century is not would-be profiteers seeking to siphon them off to make far-away deserts bloom. The biggest threat to the lakes right now is our own ignorance.

Nearly 500 years after Nicolet first nosed his canoe into the waters of Lake Michigan we are still treating the lakes the same way, as liquid highways that promise a shortcut to unimaginable fortune. Nicolet might have made an honest mistake. The same wont be said for us, because continuing to exploit the worlds largest expanse of freshwater in this manner is wreaking increasingly disastrous consequences.

YOU MAY THINK YOU KNOW THE MODERN HISTORY OF THE GREAT Lakes. The story of how by the middle of the 20th century industrial and municipal pollution smothered their beaches, of how hundreds of square miles of open water at that time were so devoid of oxygen they were declared dead, and of how the rivers that feed the lakes suffocated under chronic slicks of chemicals and oils prone to combust. And then the story of their revival, of how all the industrial plundering and wanton polluting finally spurred passage of the landmark Clean Water Act of 1972.

That law did indeed bring dramatic reductions in the wastes tumbling into the lakes, and their recovery was as fast as it was dramatic. This is why lakefronts from Toronto to Milwaukee today glimmer with the glass of luxury condos and office towers, and why the land they sit atop is among the most expensive real estate in the Midwest. This is why Clevelands Cuyahoga River, which famously exploded in flames, now draws more fishing lines than punch lines. And this is why when you cruise along Chicagos Lakeshore Drive on a hot summer afternoon you will see hundreds of people lounging on the beach and splashing in the Lake Michigan surf, all literally in the shadows of the John Hancock Center and its neighboring skyscrapers. It all gives the impression that humans and the lakes have finally learned to get along. Its a mirage.

The story of The Death and Life of the Great Lakes takes you beneath the lakes shimmering surface and illuminates an ongoing and unparalleled ecological unraveling of what is arguably North Americas most precious natural resource. Its about how the Great Lakes were resuscitated after a centurys worth of industrial abuse only to be hit with an even more vexing environmental catastrophe.

Next page