Contents

Guide

ALSO BY DAN EGAN

The Death and Life of the Great Lakes

Copyright 2023 by Dan Egan

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

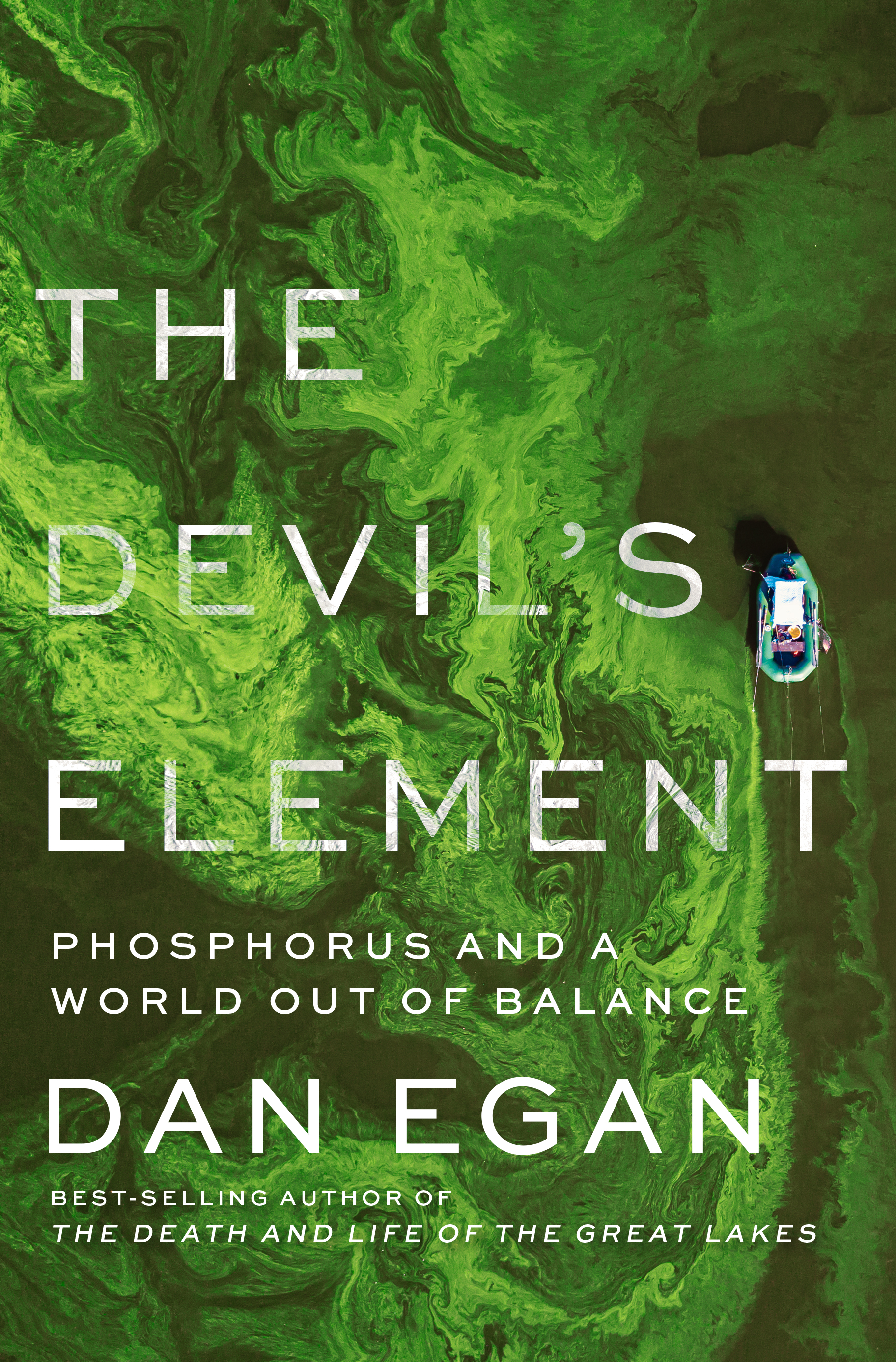

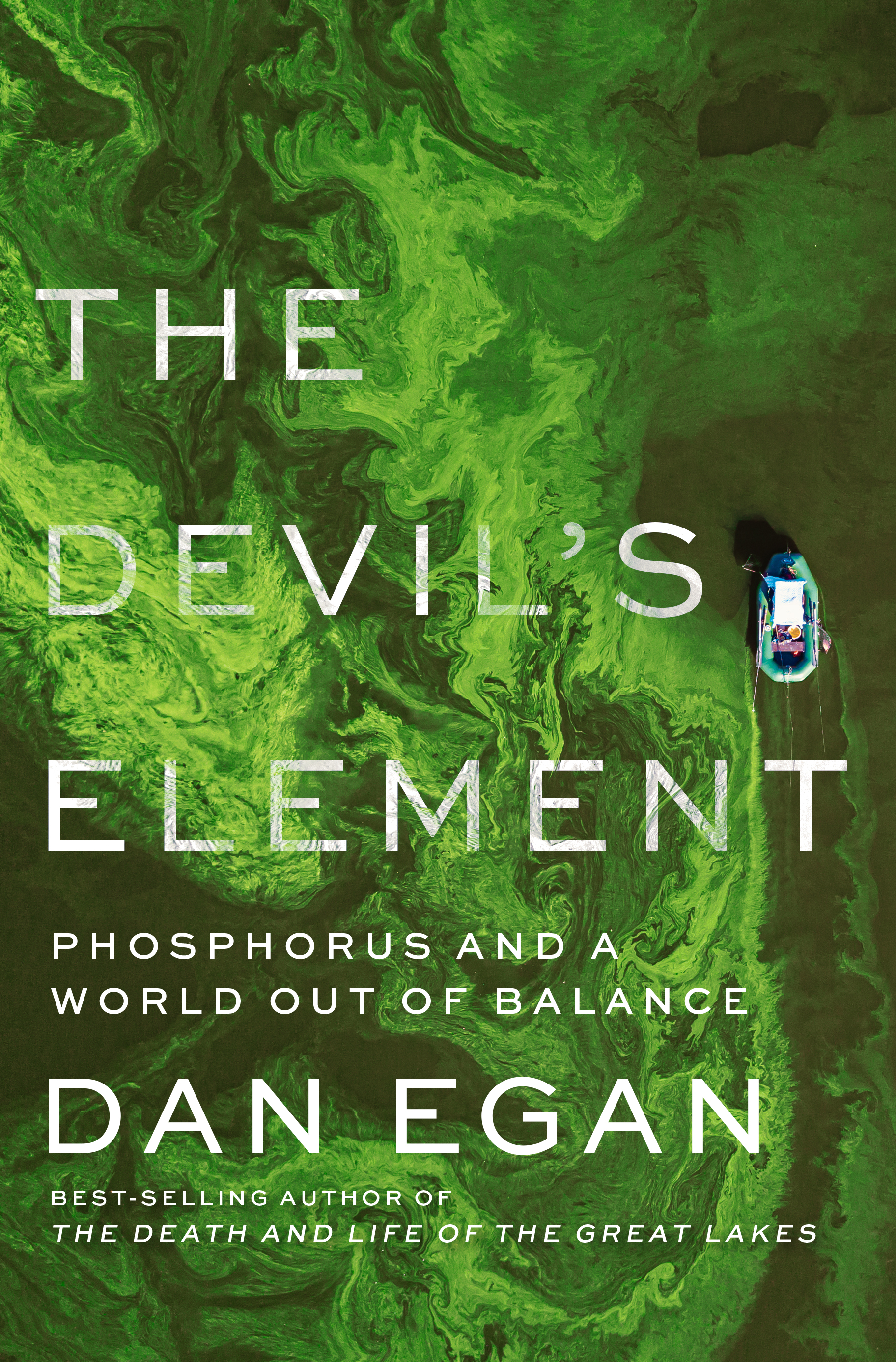

Jacket design: Steve Attardo

Jacket photograph: Sergey Muhlynin / Shutterstock

Book design by Brooke Koven

Production manager: Anna Oler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-1-324-00266-6

ISBN 978-1-324-00267-3 (ebk.)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

In memory of Christopher Marsh

CONTENTS

P ure phosphorus, element fifteen on the periodic table, does not typically exist on its own in the natural world. Even though phosphorus atoms are required by every living cell on Earth, they are naturally bound up with four oxygen atoms to form molecules called phosphates. This isnt a book about oxygen atoms, so in most all cases I will use the term phosphorus, though there will be cases in which I quote people using the term phosphate.

Similarly, I am aware that the preferred scientific term for an explosion of a type of nuisance (and sometimes poisonous) phytoplankton is an algal bloom. But the general public typically uses the term algae bloom, and the general public is the target audience for this book.

Along those lines, this book is not intended to be the last word on phosphorus. Many in the general public might not yet be aware of the phosphorus troubles the world is headed toward because of the elements dual roles as a dangerously potent toxic algae booster and as an essentialand increasingly scarcecrop nutrient. But there are scientists who have been on these problems for years, and there are a host of emerging technologies and practices to address one or both sides of the overuse-scarcity problem tied to phosphorus. This book does not provide a survey of them. I discuss some potential paths forward to put the world back into a better phosphorus balance, but this book isnt intended to provide a prescription for the phosphorus paradox. It is an introduction to it.

I n late summer 8, Abraham Duarte was roaring down a neighborhood street in Cape Coral, Florida, at highway speed when a constellation of blue and red lights started to twinkle in his rearview mirror. He ditched his black Lexus and tried to escape on foot into a tangle of backyards, but he ran out of lawn sooner than expected.

As the hard-breathing cops closed in, bodycams rolling, Duarte had two choices. He could turn around, face the jangling handcuffs and the consequences of resisting arrest after being pulled over for speeding. Or the twenty-two-year-old, who sports a tattoo on his left arm that reads Taking Chances, could swim for it.

Duarte plunged into one of the canals that cut through Cape Coral neighborhoods like so many nautical alleyways. It was the wrong choice. The problem wasnt that Duarte didnt know how to swim. It was that he didnt exactly jump into water; the surface of the canal was smothered in a brilliantly green algae goop thick as oatmealand poisonous.

Duarte screeched as toxic fumes overwhelmed him while officers on the canal bank anxiously radioed for backups to bring a rescue rope. Duartes face started to bob into the slime. One officer coached him to float on his backto keep his mouth and nose above the poison.

Fuck dawg. Fuck. Fuck. Damn. Holy shit!! Duarte wailed as he tried to dog-paddle to shore.

You need to get out of that stuff, that is gonna mess you up! shouted one officer. Seriously man, that is going to kill you.

Duartes feet finally hit bottom when he got within several yards of the canal bank. At that point it was clear he wasnt going to drown, but he wasnt out of trouble. He began to vomit violently.

As Duarte neared the canal wall, he reached up and the rubber-gloved cops heaved him ashore. They rolled him onto his stomach, handcuffed him and gave him a quick shower with a garden hose that was nearly as green as the muck coating his eyes, nostrils, and throat. Muck that Duarte said He was taken to the hospital and later charged with resisting arrest (without violence) and possession of a controlled substance.

Days after Duartes close call in the canal, even as he was recuperating from being treated for gastrointestinal and respiratory distress, television news anchors across the country smirked as they narrated the cops body camera chase video. The clip might have added to the legend of Florida Manthe internets fixation on Sunshine State males who make headlines for committing bafflingly stupid acts.

But Duartes plunge into that toxic quagmire is more than a meme.

It is an omen.

That same summer in the little city of Stuart, a beach community on the opposite side of the Florida peninsula from Cape Coral, some hundred panicked homeowners showed up at city hall in the middle of the business day to demand something be done about the same green goo plaguing their own coastal waters. It was a sweltering July day, the kind towns like Stuart are built for, but signs on the boardwalk outside city hall warned visitors:

blue-green algaeavoid contact with the water

As people at the meeting introduced themselves and stated their affiliations, it became clear this was not a typical gathering of environmentalists. They werent strategizing about how to protect some beleaguered species and the far-away lands or waters upon which it depends. These people, who represented businesses as well as homeowners associations and fishing and yachting clubs, spoke as though they were the threatened species.

, a scraggly commercial fisherman whose business had collapsed right along with the regions schools of mackerel not long after the green slime arrived. There are a lot of people like me that need help. The forty-five-year-old was suffering chronic stomach pain that was initially diagnosed as diverticulitis, and then ulcerative colitis, and then Crohns disease. Eventually doctors had given up trying to figure out what made Embrey so sick.

Embrey didnt need to spend tens of thousands more dollars on more specialists, CT scans, and lab tests to figure out the nature of his illness. He knew it was the poisoned water, and he wasnt alone.

So many patients had been showing up in local clinics and emergency rooms reporting mysterious respiratory issues and gastrointestinal illnesses that in the days before the city hall meeting the head of the local health network had To gauge the scope of the algae scourge that had become a summer fixture in Stuart over the previous few years, he instructed clinics to begin asking these patients whether they had been swimming or had other contact with open watersnot good news for a place billed as one of Floridas top ten beach towns.

Un-be-lievable, ladies and gentlemen, said the host of the meeting, a local Republican politician. For anybody out there listeningthis is real!

A famous ecologist named John Vallentyne made a dire prediction in the early 1970s: Decades of reckless industrial and municipal polluting threatened to do to North Americas rivers and lakes something akin to what reckless farming had done to the Great Plains during the Great Depressionwhen drought-parched, wind-whipped soils seeded black blizzards fierce enough to blind jackrabbits and turn hundreds of thousands of prairie settlers into environmental refugees.