HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston New York

2006

Copyright 2006 by Timothy Egan

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South,

New York, New York 10003.

Visit our Web site: www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

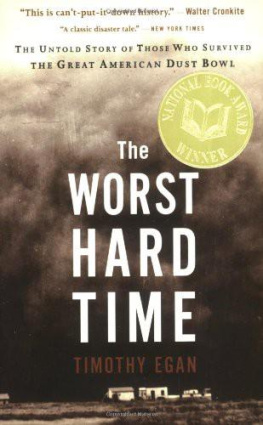

Egan, Timothy.

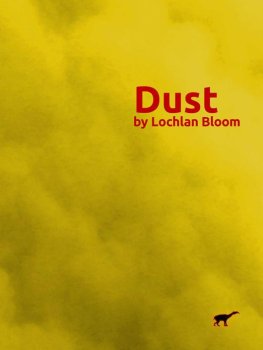

The worst hard time : the untold story of those who survived the great

American dust bowl / Timothy Egan.

p. cm.

ISBN -13: 978-0-618-34697-4

ISBN -10: 0-618-34697-x

1. Dust Bowl Era, 19311939. 2. DroughtsGreat PlainsHistory

20th century. 3. Dust stormsGreat PlainsHistory20th century.

4. Depressions1929Great Plains. 5. Great PlainsHistory20th century.

6. Great PlainsSocial conditions20th century. I. Title.

F 595. E 38 2006

978'.032 DC 22 2005008057

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

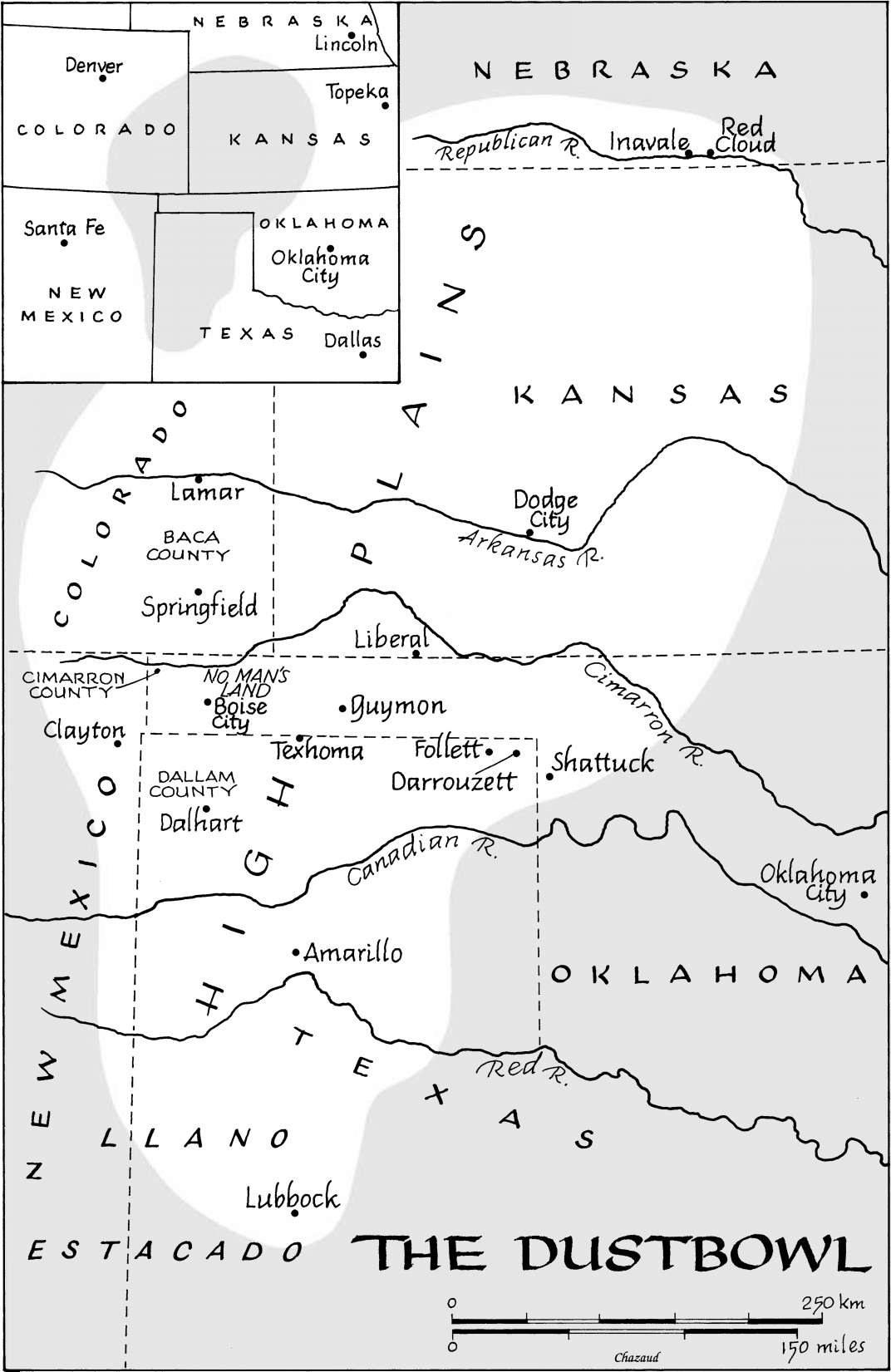

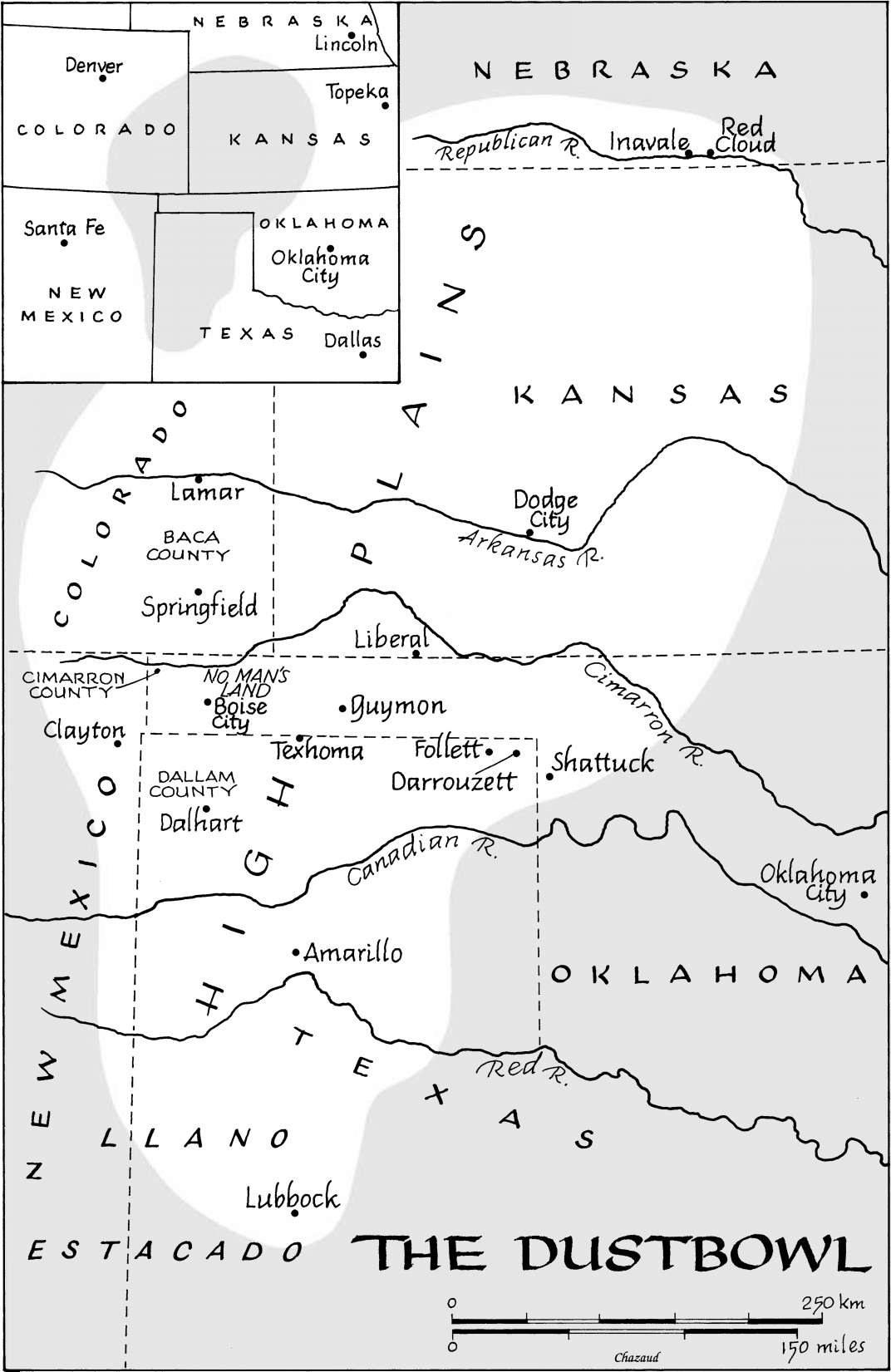

Map by Jacques Chazaud

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

QUM 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PHOTO CREDITS: Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Li-

BRARIES: ; Library of Congress, Prints & Pho-

tographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection: ,

LC-USF 34-004223- E DLC; , LC-USF34-004078-E;

, LC-USF 34-004053

E-DLC; , LC-USF34-005244-E DLC; Denver Public

Library, Western History Collection: .

To my dad, raised by his widowed mother during the darkest years of the Great Depression, four to a bedroom. Among many things he picked up from her was this skill: never let the kids see you sweat.

"Between the earth and that sky I felt erased, blotted out."

W ILLA C ATHER

Contents

Introduction: Live Through This 1

I PROMISE: The Great Plowup, 19011930

1. The Wanderer

2. No Man's Land

3. Creating Dalhart

4. High Plains Deutsch

5. Last of the Great Plowup

II BETRAYAL, 19311933

6. First Wave

7. A Darkening

8. In a Dry Land

9. New Leader, New Deal

10. Big Blows

III BLOWUP, 19341939

11. Triage

12. The Long Darkness

13. The Struggle for Air

14. Showdown in Dalhart

15. Duster's Eve

16. Black Sunday

17. A Call to Arms

18. Goings

19. Witnesses

20. The Saddest Land

21. Verdict

22. Cornhusker II

23. The Last Men

24. Cornhusker III

25. Rain

Epilogue

Notes and Sources

Acknowledgments

Index

Introduction: Live Through This

O N THOSE DAYS when the wind stops blowing across the face of the southern plains, the land falls into a silence that scares people in the way that a big house can haunt after the lights go out and no one else is there. It scares them because the land is too much, too empty, claustrophobic in its immensity. It scares them because they feel lost, with nothing to cling to, disoriented. Not a tree, anywhere. Not a slice of shade. Not a river dancing away, life in its blood. Not a bump of high ground to break the horizon, give some perspective, spell the monotone of flatness. It scares them because they wonder what is next. It scared Coronado, looking for cities of gold in 1541. It scared the Anglo traders who cut a trail from Independence to Santa Fe, after they dared let go of the lifeline of the Cimarron River in hopes of shaving a few days off a seven-week trek. It even scared some of the Comanche as they chased bison over the grass. It scared the Germans from Russia and the Scots-Irish from Alabamathe Last Chancers, exiled twice over, looking to build a hovel from overturned sod, even if that dirt house was crawling with centipedes and snakes, and leaked mud on the children when thunderheads broke.

It still scares people driving cars named Expedition and Outlander. It scares them because of the forced intimacy with a place that gives nothing back to a stranger, a place where the land and its weatherprobably the most violent and extreme on earthdemand only one thing: humility.

Throughout the Great Plains, a visitor passes more nothing than something. Or so it seems. An hour goes by on the same straight line and then up pops a town on a mapTwitty, Texas, or Inavale, Nebraska. The town has slipped away, dying at some point without funeral or proper burial.

In other places, scraps of life are frozen in death at midstride, as Lot's wife was petrified to salt while fleeing to higher ground. Here is a wood-framed shack buried by sand, with only the roof joists still visible. In the distance is a copse of skeletal trees, the bones of orchards dried to a brittleness like charcoal. And is that a schoolhouse, with just the chimney and two walls still standing? Then you see fence posts, the nubs sticking out of sterile brown earth. Once, the posts enclosed an idea that something could come from a shank of the southern plains to make life better than it was in a place that an Ehrlich, an O'Leary, or a Montoya had left. The fence posts rose six feet or more out of the ground. They are buried now but for the nubs that poke through layers of dust.

In those cedar posts and collapsed homes is the story of this place: how the greatest grassland in the world was turned inside out, how the crust blew away, raged up in the sky and showered down a suffocating blackness off and on for most of a decade. In parts of Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas, it seemed on many days as if a curtain were being drawn across a vast stage at world's end. The land convulsed in a way that had never been seen before, and it did so at a time when one out of every four adults was out of work. The people who live here now, the ones who never left, are still trying to make sense of why the earth turned on them. Much as they love this place, their doubts run deep. Was it a mistake to hang on? Will they be the last generation to inhabit the southern plains? And some feel deep shamefor the land's failure, and their part in it. Outside Inavale not long ago, an old woman was found burning a Dust Bowl diary written by her husband. Her neighbor was astonished: why destroy such an intimate family record? The horror, the woman explained, was not worth sharing. She wanted it gone forever.

Fence tops lead to small farms, some still pulsing with life, and lead further to towns that service what is left of the homestead sections. Here is Springfield, standing for another day in Baca County, in the far southeast corner of Colorado, with Kansas on its eastern side, the No Man's Land of the Oklahoma Panhandle to the south, a piece of New Mexico in another corner. For sale signs. A mini-mart. A turkey buzzard perched on a tower near city hall. Springfield is the county seat for Baca, which has about four thousand people spread over its wrinkled emptinessfewer than two people per square mile. A hundred years ago, a county with population density this low was classified as "frontier." By that definition, there is far more frontier now in this part of the world than in the day of the sod house. The town has the High Plains look, that slow-death shudder. They have not tried to dress it up or put makeup on battered storefronts. It is what it is. No flashing banners. No pretense.

A few blocks off Main Street is a house of sturdy stone. A bang on the door brings a small, brittle woman to the porch.

"I'm looking for Isaac Osteen."

"Ike?" Her voice is from somewhere long ago. "You want Ike?"

Next page