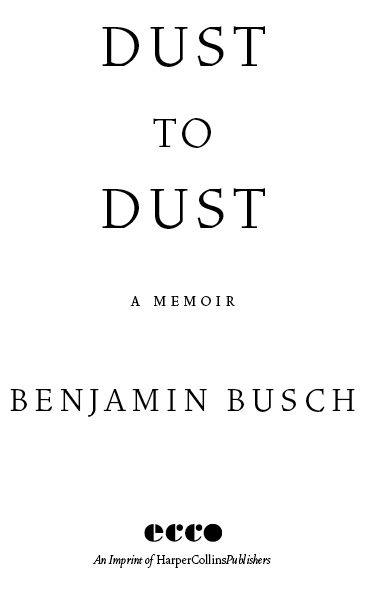

For Tracy, Alexandra, and Kyrah

Stories are... in a sense, about ending and about endings, and of course they are also the heartfelt prayer, the valiant promise, that what we have loved might live forever.

FREDERICK BUSCH, DEATHS

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

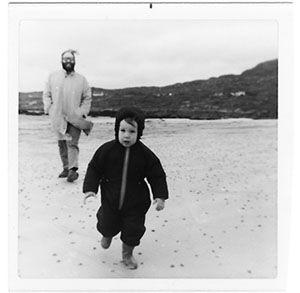

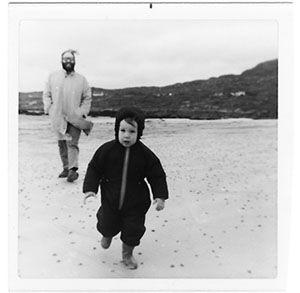

I knew very early that I was a solitary being. I longed for the elemental. As a child I was drawn into the wilderness, the reckless water of oceans, rivers, and rain, the snow and ice floes, the mountains of rock, stones, and sand, the forests, and the ruins left vacant by human decline, neglect, and tragedy. The places we had given up or could not take were what attracted me. I wandered the woods and brooks with unsubstantiated confidence, and I declared myself daring with unseasoned conviction.

It was beyond me to realize that I borrowed much of that invulnerability from the protection of my parents. They worried and were vigilant. Though they did not follow me on my adventures between breakfast and dinner, they assembled a story of where I had been when I returned hungry. They encouraged my delusions because childhood is the time for magical possibilities. I did not consider the possibility of rejection or betrayal. My ambitions imagined no losses. What could be lost?

I believed, once, that I could predetermine my journey. I wanted to create something that could not be destroyed, and to do that I had to disbelieve the evidence of destruction. I had to look at the bone and ash around me as the yield of errors, not of dreams. But I grew up and found damage, and death, and the friction of incalculable consequences. I had mapped a path through the wild with wishful premonition in my youth, but I had come to find my way by mishap and deviation. War was wilderness, and I went there, too.

The soldier arrives home to discover that the war he has returned from has already been forgotten, and because he has survived as a witness to it, neither he nor his country are innocent. Both try to dream again, the soldier by remembering himself before the war, and the country by forgetting the soldier it sent away. The legionnaire returns to find Rome in ruins, its roads still straight, leading out the way he had once marched. It is, perhaps, better that his home is deserted. It can never be what it was before, and the people who can forgive us cannot know what we have done. But the arch at the entrance to Rome still stands, its carved letters clear in the marble. It recounts only victory. The paved roads are also there, leading to conquered lands where free people dig for the buried empire, its value being in that it is now lost.

My father, a novelist, experienced the world through language. It was an intellectual relationship to the physical universe. My mother was a librarian and understood. He could write with authenticity about experiences he hadnt had, could breathe life into people he hadnt been. He found a way to live outside of booksbut not without some degree of astonishment that the things described in them often actually existed. I was different. I gained comprehension of my environment by throwing myself against it. Digging, cutting, climbing, stacking. What my father built with words, I built with pieces of the earth, stones, and wood. He wrote most about loss and failure because he feared mistakes and departures so much. Tragedy was inevitable to him, whereas I believed that the inevitable could be fought. I thought that with enough defiance, mortality could be made at least improbable.

Trilobites were unconcerned with legacy, yet we find them fossilized, their stone portraits preserved in the rock. These remains are merely impressions, their tissue and shell replaced with gray minerals, death masks rising back to the surface. I have felt the sun and wind on my face, and though I remember the sensations imperfectly, there is an imprint I carry.

Childhood is still present in me. I can hear my own echoes now, elliptical, my voice changed but not the wonder I had. In seeking to disinter my childhood, I have found it unburied.

Chapter 1

I was not allowed to have a gun. My parents were fresh from Vietnam War protests, and they had no intention of raising a soldier. My mother was against the idea of toy weapons, and my father quietly supported the embargo. He had been a boy once, though, and was a war baby. His father, Benjamin Busch, had been a sergeant in the Tenth Mountain Division, fighting German troops in the Italian Alps. My mothers father, Allan Burroughs, had been a Marine in the Guadalcanal campaign against the Japanese. He called me Little Son of a Gun, but I continued to have no guns at all.

I spent much of my childhood constructing forts in our backyard and gathering local boys for epic battles. Each spring the cornfield nearby was plowed and flat river stones rose in the rows for me to harvest. I spent the cool mornings walking the furrows and hauling pieces of lost sea ledges and mountains back to my fort site. The afternoons I spent laying them in place. I built thick stone walls and dug in, preparing for siege. No contingencies were made for escape or surrender. I played an officer wielding a maple-stick sword and falling early under withering fire. As I had no sidearm or rifle, I could not reasonably hope to survive a gunfight, and I honored those odds. No one ever came within stabbing distance, and I could never reach the enemys line. Not realistically. Everyone else had something with a trigger. But casualties in war games came without consequence. There was no death in dying.

My father watched through the kitchen window, but I could never tell his mood as an observer of my recurring death. It was a small window and he was far away. One day in 1974, after I fashioned myself a rifle out of a length of old pipe, wire, and a board, my father turned to my mother and said, Well, fairs fair, and for Christmas that year he bought me a toy M1 Garand, the same kind of rifle carried by my grandfathers in the war. It had a solid wooden stock, a metal barrel, and a wooden bullet painted gold and glued to the bolt inside. It could not fire, of course, but it was perpetually loaded. I went out into the vocal battle of children at war and sometimes, with my rifle, didnt die.

The fort grew from a simple stone barricade to a two-story wooden eyesore cloaked with bedsheets and ringed by a trench. Boards were hard to come by, so the structure evolved unevenly with what I could find discarded from projects around town. There wasnt enough wood to sheath the walls, so I used the old sheets my mother had draped over tomato plants in the garden during frosts. The rusting nails that held the cloth bled long orange stains from rains, and the fort always smelled damp. It became my focus of effort, and I continued to patch and expand the building for years, manning it every day. It had in it more nails than any house in town, and it would never be finished. My grandparents each visited once a year, and I would eagerly invite my grandfathers to inspect the fort. I knew they had both been in a war and would have good advice. My fathers father would stand at a distance smiling at the complexity of the ideas at work, but I could tell he was disappointed by my craftsmanship. I explained the temporary use of the cloth as an excuse for what was still poor construction without it. My mothers father saw it differently. He would stroll out to the trench beside me with a cigarette and a glass of bourbon, and we would sit there for a few minutes. I crouched down in my trench and he sat on the edge with his feet inside, the ditch only as deep as his knees.

Next page