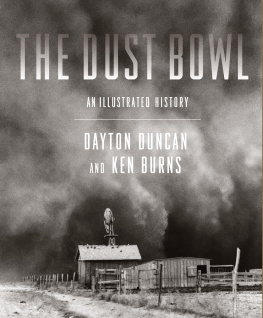

It was a decade-long natural catastrophe of biblical proportions

when the skies refused their rains; when plagues of grasshoppers and swarms of rabbits descended on parched fields; when bewildered families huddled in darkened rooms while angry winds shook their homes, pillars of dust choked out the mid-day sun, and the land itselfthe soil they had depended upon for their survival and counted on for their prosperityturned against them with a lethal vengeance.

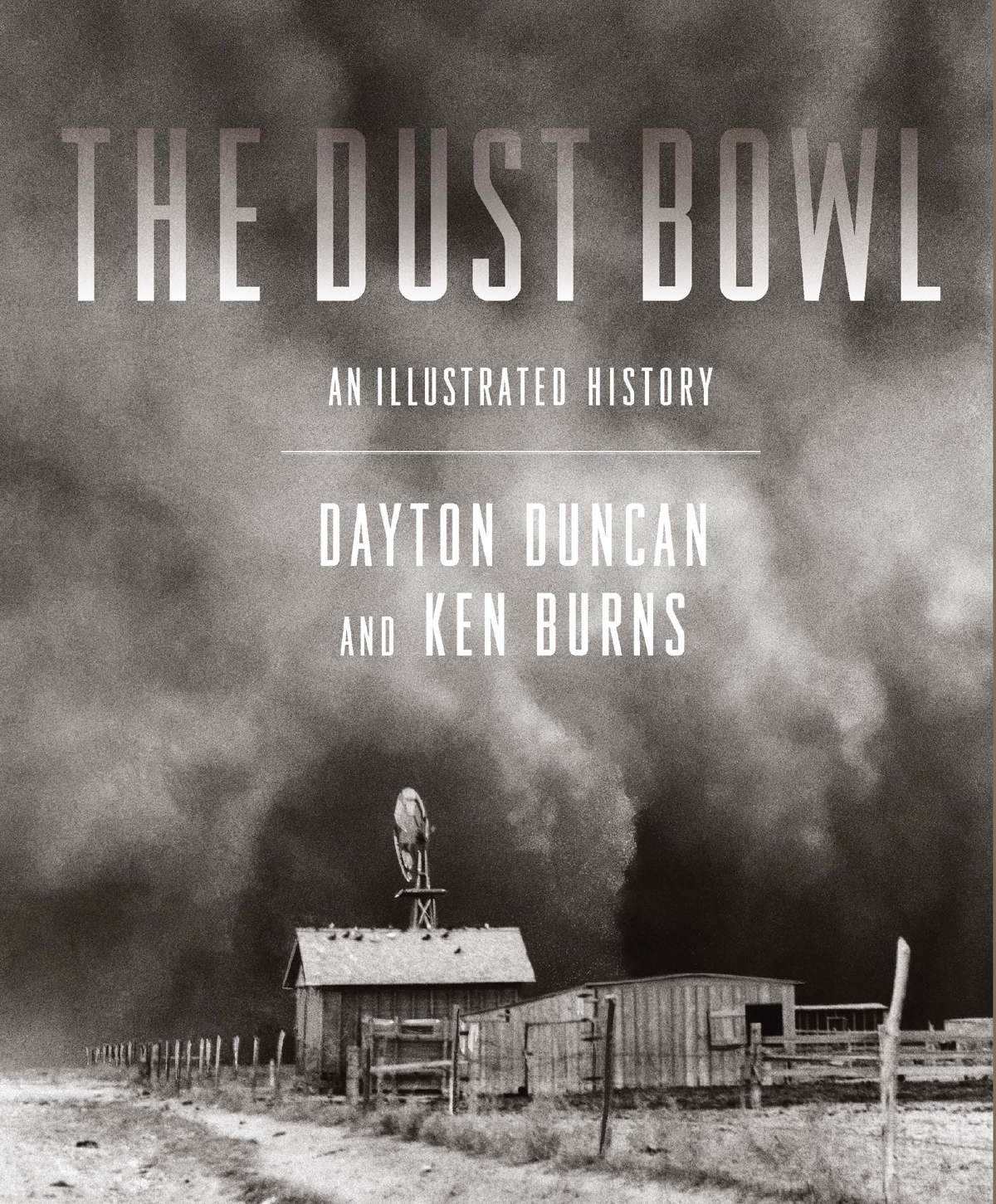

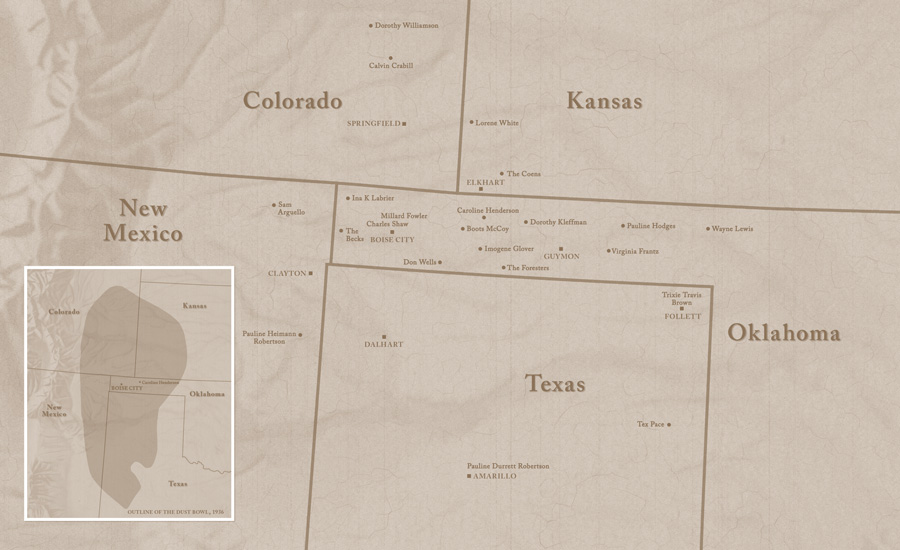

[Plate 2]

A dust storm descends on a solitary farmstead, 1935.

It was the worst man-made ecological disaster in American history

when the irresistible promise of easy money and the heedless actions of thousands of individuals, encouraged by their government, resulted in a collective tragedy that nearly swept away the breadbasket of the nation.

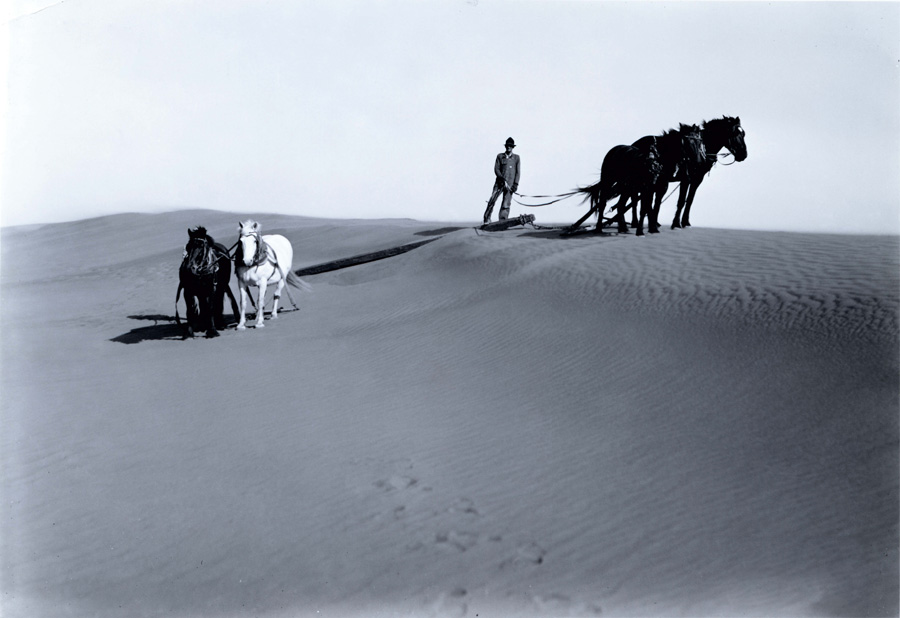

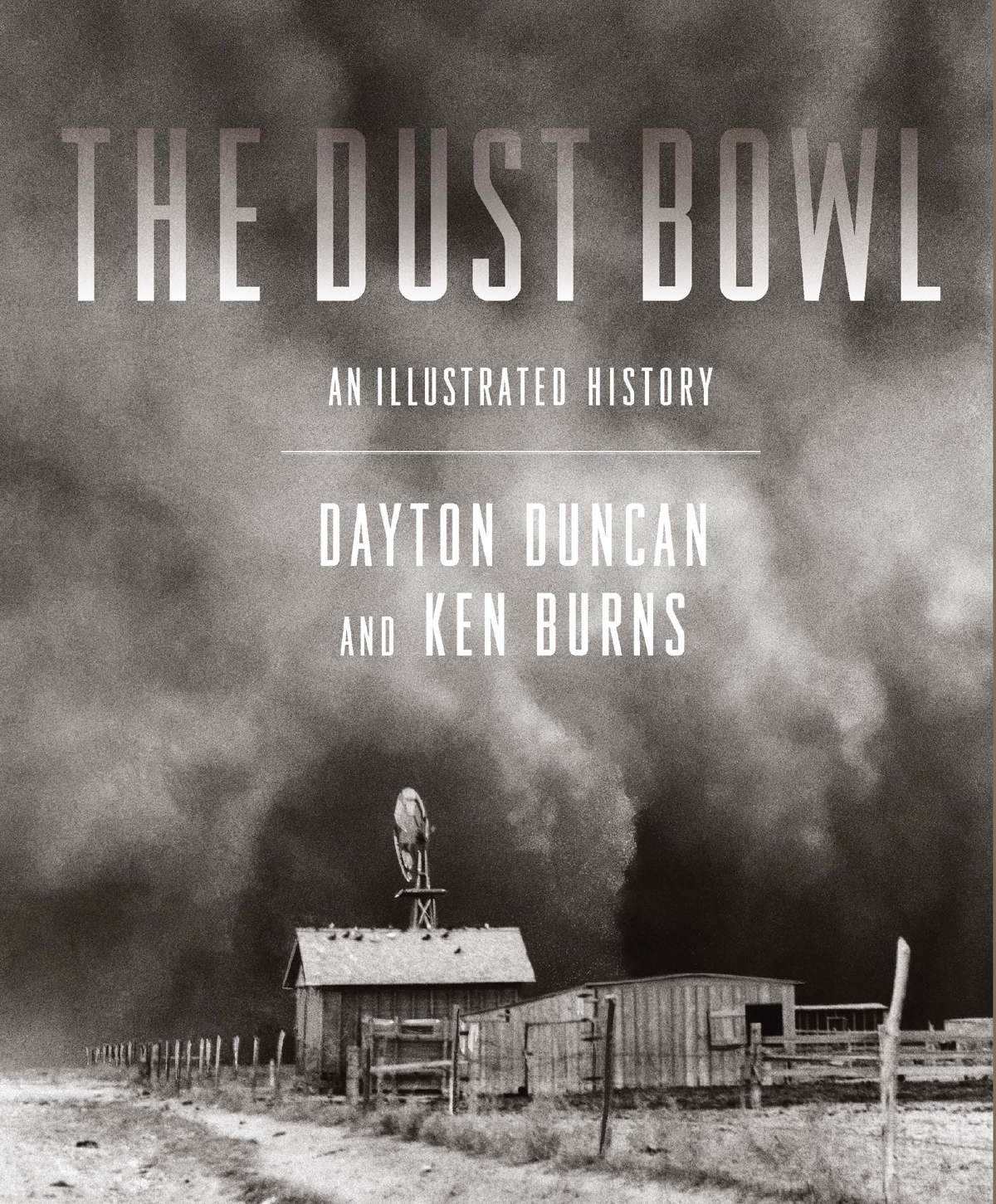

[Plate 3]

A Texas farmer attacks a sand dune with his team of horses and a drag pole.

It was an epic of human pain and suffering

when normally self-reliant fathers found themselves unable to provide for their families; when even the most vigilant mothers were unable to keep the dirt that invaded their houses from killing their children; when thousands of desperate Americans were torn from their homes and forced onto the road in an exodus unlike anything the United States has ever seen.

[Plate 4]

Three Kansas children head for school wearing goggles and homemade dust masks.

But the story of the Dust Bowl is also the story of heroic perseverance

of a resilient people who, against all odds, somehow managed to endure one unimaginable hardship after another to hold onto their lives, their land, and the ones they loved.

[Plate 5]

A man struggles against a sandstorm in the Texas Panhandle.

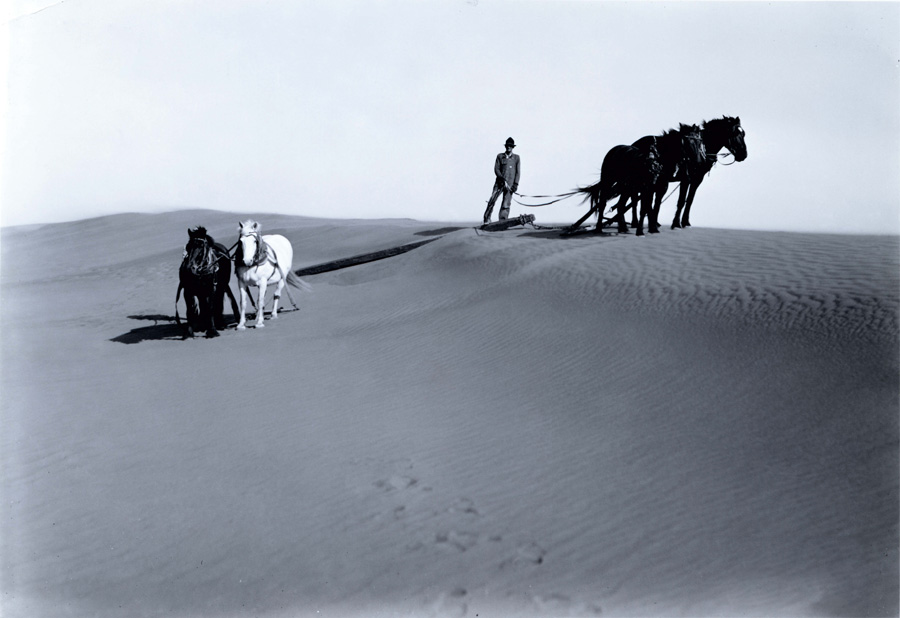

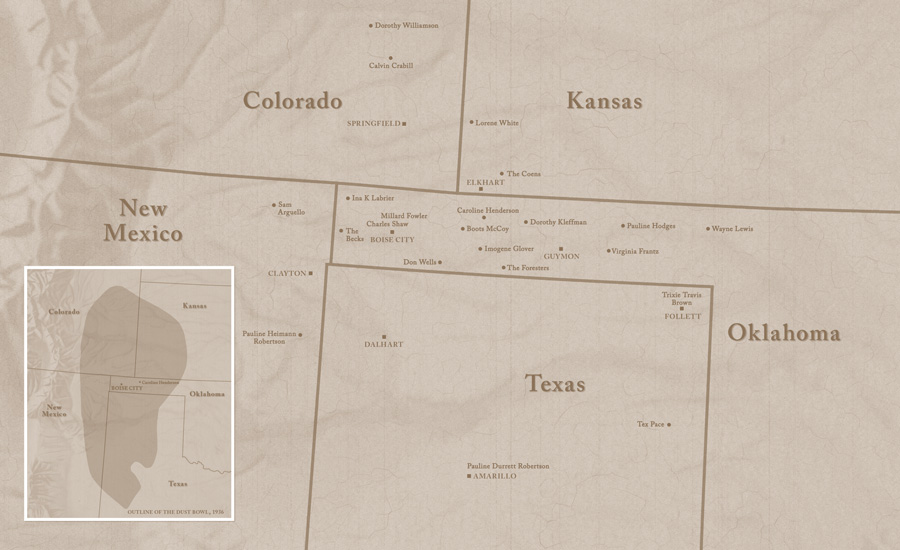

[Plate 325]

A dust storm bears down on the town of Darrouzett, Texas.

[Plate 324]

A black blizzard descends on Hooker, Oklahoma, June 4, 1937.

[Plate 326]

LISTENING TO THE LAND

[Plate 6]

Two chickens head for cover near Ulysses, Kansas.

[Plate 7]

A scene along Highway 51 in Baca County, Colorado, in the 1930s.

That country was so flat, you know. You could see for just miles. And they used to say that there wasnt a fence between there and the North Pole.

The grass was buffalo grass, and it was so goodit was unbelievable, it was so thick. God, it was good grass country. Man, it was perfect.

Robert Boots McCoy

Texas County, Oklahoma

FOR A TRAVELER DRIVING SOUTH DOWN US 385/287 through the flat relentless expanses of first Prowers and then Baca County, Colorado, in the southeastern corner of that state, heading toward Oklahoma and the geographical heart of the ten-year disaster known as the Dust Bowl, it is impossible not to notice the relative stability and even peace of the landscape. Part of it is irrigation, of course, the modern wells and the giant-wheeled watering machines that suck up and distribute the scarcest commodity on the southern Plains.

Passing through Campo, the last town in Colorado, that landscape of immense farms and pasturage changes. One is near the center of the Comanche National Grassland, part of an immense federal effort starting in the 1930s to save the land that was once blowing away, convincing farmers to abandon the questionable agriculture practices that had for decades compelled the frantic human effortand sufferingthere, and return it to its natural state. The cottonwoods, willows, and locusts seem forlorn and sometimes bent, on guard, it almost seems, against the memory of forces once unleashed there, perhaps to come again.

A constant breeze stirs everything. Every green thing, the grasses, the thistles, the sagebrush (the fag end of vegetable creation, Mark Twain once called it) are all in perpetual frantic animation, like the jerky, spastic motion of an old silent movie. Periodic crosses in the ditches just off the highway memorialize momentary mistakes at 75 miles per hour.

Leaving the relative lushness, if that is what can be said of it, of Baca County and entering Cimarron CountryNo Mans Land it was once called, at the extreme western end of the Oklahoma Panhandleyou realize you must be in a desert. Is it? Was it? Will it always be? Dead cottonwoods line the banks of the near bone-dry bed of the Cimarron River that, one is assured later, does run wet some of the time. Dust devils dance off to the left and then the right, innocent playful reminders of the devastating plagues that once beset this place.

[Plate 8]

Two daughters and their worried father, 1938.

It is a post-apocalyptic world. Something happened here, and it is hard to even imagine agriculture ever thriving in this drynessor a mountain range of dust coming at you, threatening everyone and everything dear to you. The first rise in miles is just a tumbledown butte, where whitewashed rocks, painted and arranged by the hands of still unseen humans, advertise S T . P AULS M ETHODIST C HURCH down the road in the once dishonestly named Boise City.

But over a rise and beyond a graceful arcing bend in the blacktop, green fields suddenly stretch out as far as the eye can see and the landscape returns once again to flatness. Beautiful crops of grass and wheat, even high-maintenance corn (thanks to those giant water walkers that overrule the usual poor odds of moisture) unfold, which then just as fast yield to grazing land and weeds and back to cultivated land again. Farm buildings announce human habitation. The pickups pass with increasing frequency, their drivers waving in the custom of the Plains, a gesture of genuine friendliness that mitigates and helps to abolish the genuine loneliness of the mind-numbing distances required to do almost everything: shop, go to school, get to the hospital. The car radio anxiously cycles and searches and finds only one FM station, KJIL (Jesus Is Lord), where even the commercials earnestly cite scripture, and the conversation that day, without a hint of irony, is a scientific defense of the great biblical flood that washed away all but one human family. Out in the vast emptiness, any traveler might find comfort in its certainty and companionship.