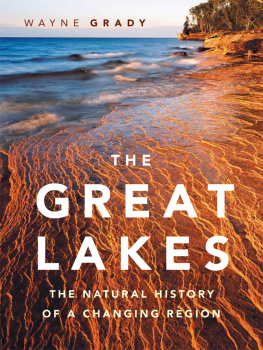

THE GREAT LAKES

Evening paddle on Smoke Lake in Ontarios Algonquin Provincial Park.

WAYNE GRADY

PRINCIPAL PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRUCE LIT TEL JOHN ILLUSTRATIONS BY EMILY S. DAMSTRA

THE

GREAT LAKES

THE NATURAL HISTORY

OF A CHANGING REGION

D&M PUBLISHERS INC.

VANCOUVER /TORONTO/BERKELEY

Text copyright 2007 by Wayne Grady Photographs copyright 2007 by the photographers credited First paperback edition 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada V5T 4S7

www.greystonebooks.com

David Suzuki Foundation

219-2211 West 4th Avenue

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada V6K 4S2

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-55365-197-0 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-55365-804-7 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-55365-893-1 (ebook)

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reproduce or quote from their works:

Margaret Atwood for Lichen and Reindeer Moss on Granite, Margaret Atwood, 2007. Used by permission of the author.

Diana Beresford-Kroeger for a quotation from ArboretumAmerica: A Philosophy of the Forest, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2003.

Robert Finch for lines from Lake, included in Sail-boat andLake, The Porcupines Quill, Erin, Ontario, 1988.

Lines from Lake Superior by the late Lorine Niedecker are from North Central, Fulcrum Press, London, 1968.

Andrew Nikiforuk for a quote from Pandemonium: BirdFlu, Mad Cow Disease and Other Biological Plagues of the 21stCentury, Viking Canada, Toronto, 2006.

The University of Minnesota Press for a quote from Runes ofthe North, by Sigurd F. Olson, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1997.

The heirs of Rutherford Platt for permission to quote from The Great American Forest, by Rutherford Platt, Prentice-Hall Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1965.

Copy edited by Barbara Czarnecki

Cover design by Naomi MacDougall

Front cover photograph Willard Clay/Getty Images

Maps by Eric Leinberger

Distributed in the U.S. by Publishers Group West

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

CONTENTS

ADVISORY PANEL

DR. LINDA CAMPBELL

Department of Biology

Queens University

Kingston, Ontario

DR. JOHN M. CASSELMAN

Senior Scientist,

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Aquatic Resources and Development

Adjunct Professor of Biology,

Queens University

Kingston, Ontario

DR. ROBERT W. DALRYMPLE, PGEO

Department of Geological Sciences and Geological Engineering

Queens University

Kingston, Ontario

DAVE DEMPSEY

Biodiversity Project

Madison, Wisconsin

DR. ADRIAN FORSYTH

Research Associate,

Smithsonian Institution

Vice-President, Programs

Blue Moon Fund

Washington, D.C.

DR. KAREN LANDMAN

School of Environmental

Design and Rural Development

University of Guelph

Guelph, Ontario

DAVID OTOOLE

Director, Urban and Rural

Infrastructure Policy

Ontario Ministry of Transportation

Ontario Representative,

Great Lakes Commission

Toronto, Ontario

RON REID

Executive Director,

The Couchiching Conservancy

Orillia, Ontario

Precambrian rock and white pine, Georgian Bay, Ontario.

A bull moose enjoys a tranquil meal in a shallow northern lake.

T HE GREAT LAKES ENDURE THE fate of all familiar features in nature: they are taken for granted equally by those who know them and by those who dont. Like mountain ranges or prairie skies, their size makes us forget theyre there; we may cast a glance at them in the morning to make sure the universe is arranged more or less as it had been the previous night, but then we dont think of them for the rest of the day. When I lived in Toronto and visitors asked me how to get to the lakefront, Id have to think before replying, Oh yes, go south. When I moved to Kingston, Ontario, and was asked the same question, Id be turned around: Its southno, east! In Windsor, on the Detroit River, where I was born, it was: Up that way, north. The simple truth is that, to me, the Great Lakes seem to be everywhere.

I have lived on them all my life, except for a brief period spent in northern Quebec, and even then I felt connected to the Lakes by the St. Lawrence River. Windsor is an upside-down Canadian city: we looked north to the United States. I remember skating on Lake St. Clair, on transparent ice that had frozen so quickly its surface held the shape of waves. I looked down giddily between my skates to see schools of minnows darting among fronds of bottom-anchored plants. I recall swimming in Lake Erie, off Point Pelee, and being taken to visit the bird sanctuary established in Kingsville by the legendary Jack Miner, who saved the threatened Canada goose from extinction. My father, too, had been born in Windsor, and although he spent World War II on the North Atlantic, when the war was over he brought his Newfoundland bride back to his hometown because, as he said, he missed the water.

My great-grandfather had moved to Windsor from Cass County, Michigan, at the end of the nineteenth century. Cass County and its seat, Cassopolis, was named for Michigan Territorys first governor, Lewis Big Belly Cass, who, with the geologist Thomas McKenney and Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, the future Indian agent, explored the country around Lake Superior in 1825. By the time my fathers family moved to Michigan, shortly after the American Civil War, Cass County was a major stop on the Underground Railroad. Andrew Jackson Grady had a cup of coffee there, as they say in baseball, and then moved on to Windsor.

We later lived for a time north of Toronto, not far from Lake Simcoe, part of the ancient water route through which, 4,000 years ago, Lake Huron drained directly into Lake Ontario, bypassing Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River and Lake Erie. I fished for chub in the narrow creeks that cut through pastures and cedar bushes, watched ducks and turtles and frogs in the few remaining wetlands in the area, and tobogganed in valleys laden with snow in the lee of the Niagara Escarpment. My brother now lives in Sault Ste. Marie. The web of my family thus embraces all five Lakes and two of the three waterways between them.

Even so, I did not fully appreciate the Lakes until I boarded a freighter in Thunder Bay, at the western end of Lake Superior, and sailed through all five as the ship carried a load of wheat to the St. Lawrence. Standing on a throbbing deck, under the limitless expanse of sky, I lost sight of land in every direction. It took us all night to sail the length of Lake Superior, and I saw no other lights but the stars. The historian Arthur Lower, who had made the same journey three decades earlier, wrote that Superior is impressive at all times, never more so than at midnight. Impressive, yes, but also somehow comforting, as though the knowledge of all that clear sky above us, and all that freshwater beneath us, and our ability to traverse both in safety, suggested to me that our survival as a species was both miraculous and assured.

Next page