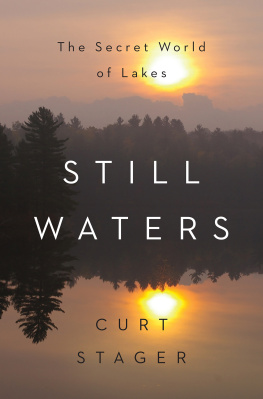

B OOKS SHOULD SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES and long prefaces are indulgent, but there are a few things to be said. First, writing this was no chore. I have worked with freshwaters and particularly lakes since the accidents of fate and personality, completely uninfluenced by a bureaucracy of professional careers advice, led me to a PhD project on two small ponds near Bristol. The background to that came in 1960 from the inspiration of a course at Preston Montford Field Centre on Meres and Mosses, run by Charles Sinker, leavened by a parallel course from the then all-female Bedford College, taught by Francis Rose, and his demonstrator, David Bellamy, onto which we were co-opted when Charles was administering the Centre. The key influences after that were the second-year limnology lectures in 1963, concocted as he went along from a pile of reprints, by Frank Round at the University of Bristol. I still remember the complete fascination of thermal stratification and the phytoplankton spring growth. Since then, lakes have been a continuous part of my life and still are. If the writing in this book occasionally touches on the acid, it is because both freshwaters and freshwater ecologists have been sorely tried, in Britain at least, over the past several decades. But in a book written mostly for a British and Irish audience, you may put it down also to dry humour. It was a pleasure to write specifically for the natives and not to have to sanitise everything for a global clientele.

The second point is an apology to Wales and the Welsh. There was no way that I could work Llyn or Llynoedd into a title that needed to look attractive and sound lilting. And yes, I know that Loughs is pronounced in Gaelic with a hard ending, like Lochs , but many people use the soft ending, and that served my purposes well. I have at least taken a very pro-Welsh standpoint in the body of the text.

Lastly, an explanation for some of the approach I have taken. The New Naturalist series has an admirable policy of minimising clutter in the text by avoiding too many references and spurning scientific names, in favour of common ones. I have dealt with the first issue by using a system of notes at the end in which to give the references. The background evidence for any ecological subject is now extensive and the 400 or so I have had to quote really does represent a minimum in an area where at least 5,000 new papers emerge every year. I have used British and Irish work where I could, but science is an international endeavour and it would be foolish to be parochial. The number of authors on scientific papers has increased steadily, indeed logarithmically, over the past fifty years, from a mean of 1.5 in the 1960s to around four in the last 5 years with sometimes as many as 50. There are interesting reasons for this, mostly concerned with the organisation and sociology of science (see Moss, 2013), but from the point of view of printing costs it means that many references now take up much more space than former ones did. Consequently, in the list of references I have quoted all authors for papers with four or fewer, but simply the first author and others for the rest. That makes for some injustice, especially in areas where the convention is that the last author is the most important (because he or she raised the funds to do the work, whilst the first author is often the graduate student who was supervised to carry it out) but the full list will be available in the original reference. Some of the original papers may require access to a university library because journal subscriptions are high, but the trend now is for free and open access on the web and a little searching will often produce free copies of many that were previously inaccessible to a general readership.

I have had to take a hybrid approach to the issue of common versus scientific names. There are well-known common names for higher plants, fish, birds and mammals, but the natural history of lakes depends also on a great many microorganisms and invertebrates, for which there are none. I have minimised lists of names, but sometimes have had to use scientific ones. The consolation is that the scientific names tell a great deal more than the common names once the system, which is very straightforward, is understood. A little dalliance with Latin improves appreciation of the meanings, but is not essential. I have given both scientific (in italics) and common names where available in the Index. To my regret, I could not find a way of mentioning Micrasterias mahabuleshwarensis var wallichii , a green algal desmid with a hint of exotic connections that is said to be found in some English lakes, but I hope that you will enjoy the book nonetheless.

Brian Moss, Liverpool, February 2015

EDITORS

SARAH A. CORBET, S C D

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIB IOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIH ORT

P ROF . JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

P ROF . BRIAN SHORT

*

The aim of this series is to interest the general

reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing

the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.

The editors believe that the natural pride of

the British public in the native flora and fauna,

to which must be added concern for their

conservation, is best fostered by maintaining

a high standard of accuracy combined with

clarity of exposition in presenting the results

of modern scientific research.

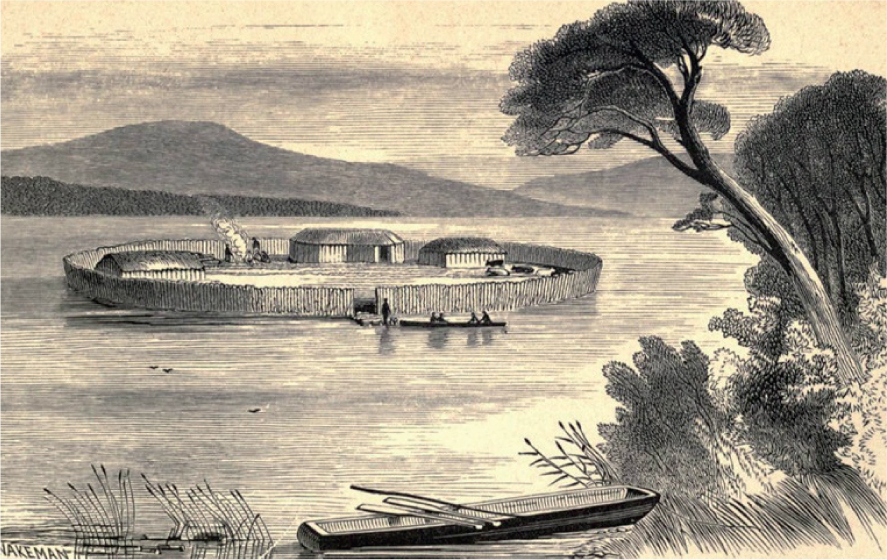

W E START EARLY, BUT, OF course, long after the true beginning The sun, setting behind the mountain ridges to the west, darkened the shoreline of the loch yet still blazed on the palisade surrounding the island; the dip of a paddle disturbed the heron that had been fishing from the submerged rock causeway, which, if you knew its zigzags, would lead you to the crannog gate ( The shoal of small perch, which the heron had been stalking by the causeways edge, began to move into the open waters. Copepods, their day spent in the deep waters, were on their way upwards to filter their food near the lakes surface, but in the twilight also to risk their lives to the hungry perch. The boatman felt no particular significance of the times; we would call it the Iron Age; he was about his daily routine.

Nightly he returned, from penning his cattle in a compound of gorse and thorn on the nearby shore, to the small island of timbers and boulders. It had been built long ago, and his family felt safe surrounded by water and the palisade. The heron settled in an oak, part of the forest that gave way to alders near the lakes edge, and studied the small fields that had been wrested from the woodland. The movements of the fish away from the shore had frustrated her fishing but there might be an eel slithering through the grass, or a snake. The man had brought some lapwings he had snared, and pots he had bartered for fish, and the smoke of his familys fire merged in the wind with that of the dozen other crannogs set around the loch.

FIG 1. Reconstruction of a crannog. Etching from Wood-Martin (1886), The Lake Dwellings of Ireland .

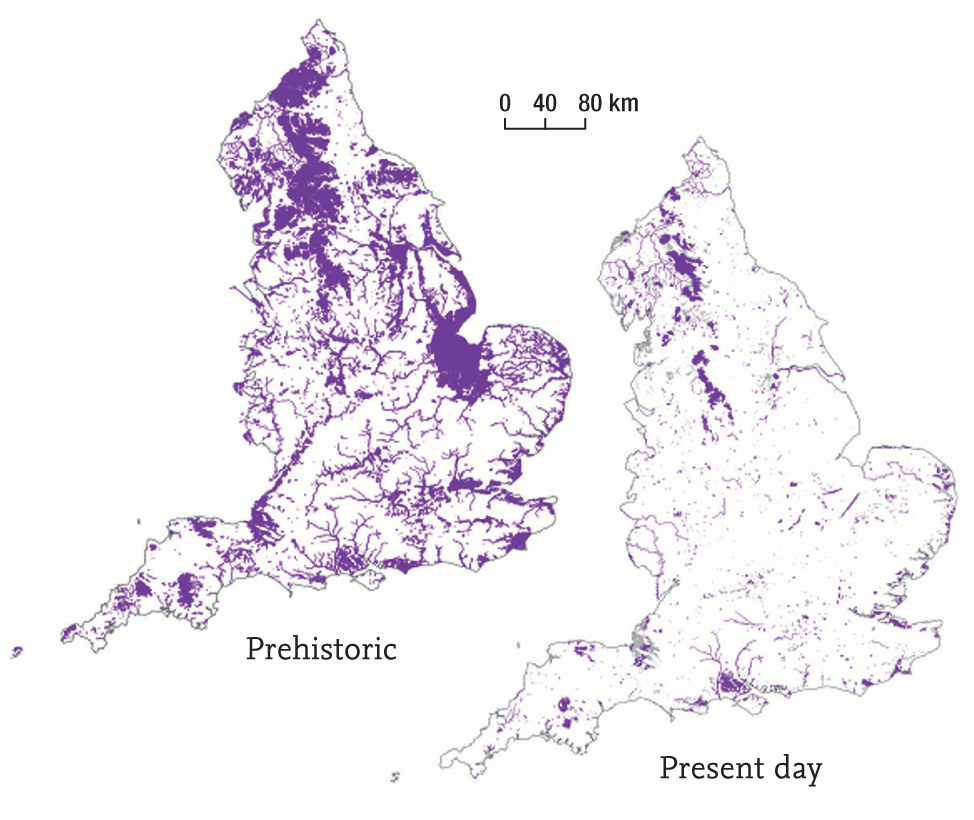

FIG 2. Distribution of wetlands in England in the prehistoric period, about 7,000 years ago and at present. Based on maps made by Wetland Vision (2008).

To the southwest, in Ireland, his distant Gaelic relatives also heard the harsh call of a heron during their evening routine but young sea trout took the place of perch in the lough; perch had not reached Ireland before the rising seas had cut it off as an island, 6,000 years previously. The copepods were there though, easily transported as eggs in the damp crevices of birds feet, and had long made their day-and-night migrations. To the south, in what was to be called England, a warmer, drier landscape harboured fewer lakes and wetlands, though the land was still well watered (). As everywhere and always, human settlements were drawn by need to lakes and rivers, springs and streams. The water stitched the landscape together; it was (and is) as the bloodstream is to the body.