This edition first published in 2018

Unbound, 6th Floor Mutual House, 70 Conduit Street,

London W1S 2GF

www.unbound.com

All rights reserved

Richard Moss, 2018

The right of Richard Moss to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduce herein, the publisher would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any further editions.

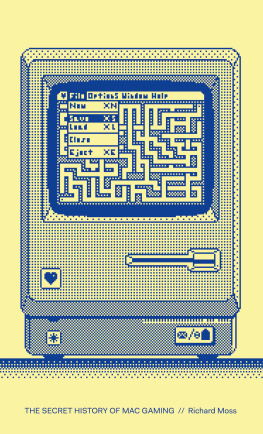

Design and art direction by Darren Wall

Case and chapter opener illustrations by JJ Signal

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78352-486-0 (trade hbk)

ISBN 978-1-78352-487-7 (ebook)

ISBN 978-1-78352-485-3 (limited edition)

Printed in Spain by Novoprint

RICHARD MOSS is an award-winning writer and journalist based in Melbourne, Australia. He has written extensively about video games and technology for more than two dozen publications, including Ars Technica , Gamasutra , Mac | Life , and Rock Paper Shotgun .

Richard also produces the podcasts Ludiphilia , which shares stories related to how and why people play, and The Life and Times of Video Games , which chronicles the history and culture of video games through short documentary-style episodes.

DEAR READER,

The book you are holding came about in a rather different way to most others. It was funded directly by readers through a new website: Unbound. Unbound is the creation of three writers. We started the company because we believed there had to be a better deal for both writers and readers. On the Unbound website, authors share the ideas for the books they want to write directly with readers. If enough of you support the book by pledging for it in advance, we produce a beautifully bound special subscribers edition and distribute a regular edition and ebook wherever books are sold, in shops and online.

This new way of publishing is actually a very old idea (Samuel Johnson funded his dictionary this way). Were just using the internet to build each writer a network of patrons. At the back of this book, youll find the names of all the people who made it happen.

Publishing in this way means readers are no longer just passive consumers of the books they buy, and authors are free to write the books they really want. They get a much fairer return too half the profits their books generate, rather than a tiny percentage of the cover price.

If youre not yet a subscriber, we hope that youll want to join our publishing revolution and have your name listed in one of our books in the future. To get you started, here is a 5 discount on your first pledge. Just visit unbound.com, make your pledge and type mac5 in the promo code box when you check out.

Thank you for your support,

Dan, Justin and John

Founders, Unbound

TO MUM AND DAD, FOR EVERYTHING.

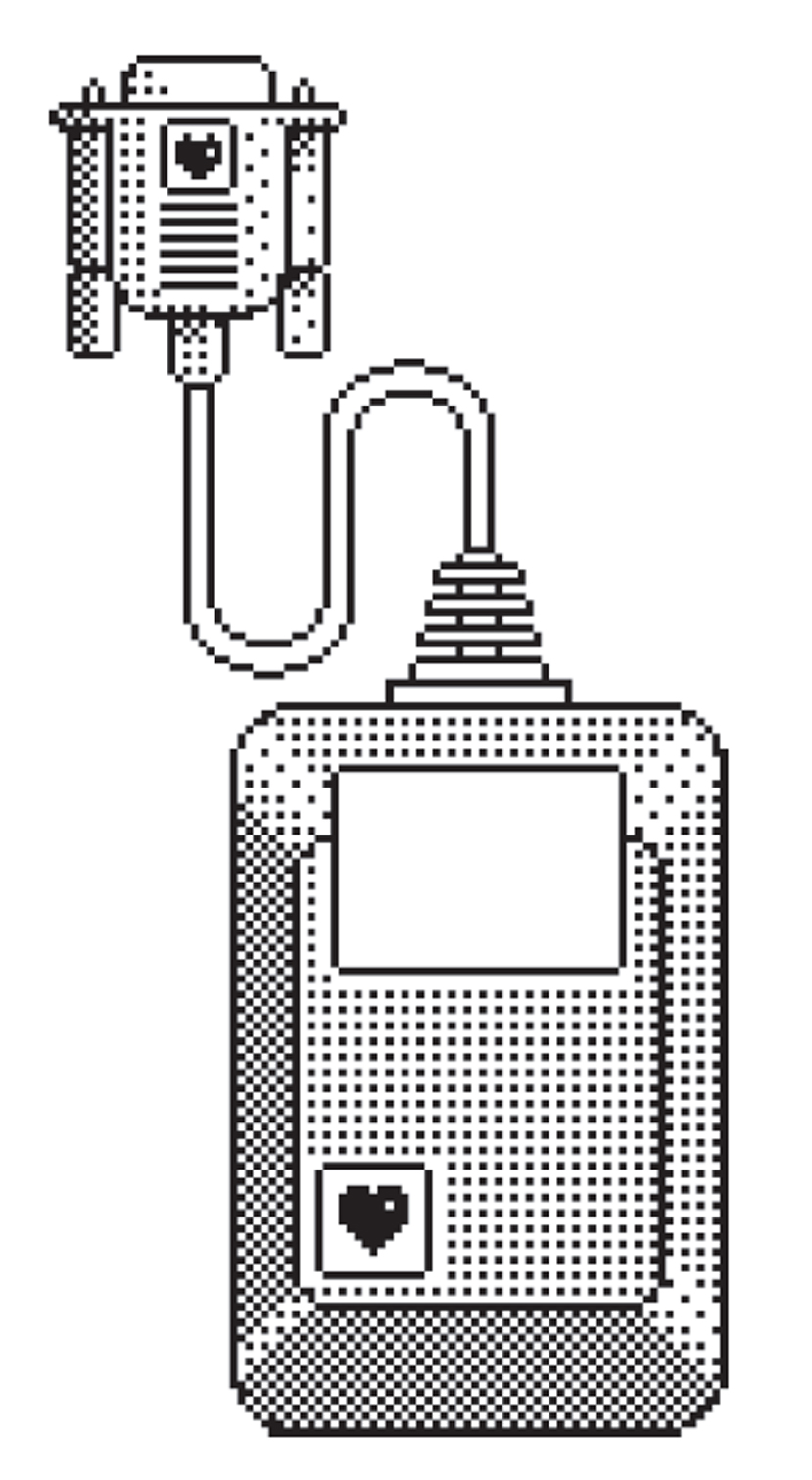

The original Macintosh mouse, Apple Computer, 1984

INTRODUCTION

by Richard Moss

I set out on this journey in July 2014 with a simple goal: I wanted to show that the Mac was important to the annals of video game history, and to share the stories behind the wonderfully creative and

imaginative Classic Mac era from the Macs mid-1980s introduction to the early 2000s. I hoped to shine a spotlight on people and ideas that have never received the attention they deserved. I believed that Think Different was more than a marketing tagline, and that Apples famous 1984 ad shown in the prime Super Bowl advertising slot ahead of the Macs January 1984 introduction was not just creative marketing spin. I felt that the Mac really did change everything, that its users really did think differently and produced software and art that was revolutionary.

In the process of pursuing that goal, Ive discovered a community more vibrant, diverse, creative, and intelligent than I had ever imagined.

Mac game fans were no angels portions of them abused and derided their heroes for petty reasons such as delays, cancellations, or working with a perceived enemy (Microsoft), just like game fans elsewhere but taken on the whole they were remarkably generous and accepting. They embraced weird ideas and supported originality. The community was small enough that even in the late 1990s, when PC and console gaming were growing huge, they could talk directly to their game development heroes.

In a world where Apple is now a major lifestyle brand and its products are mainstream accessories and appliances, its also useful to remember a time when the Cupertino company was the underdog when its only followers were the true believers of the Macintosh way, of this idea that computers should just work and that even serious software should be pleasant to use. Its valuable, too, to see what people achieved when they were absorbed in that aesthetic.

When the rest of the personal computing world had low-resolution, blocky graphics with just a handful of garish colours and a bewildering keyboard-driven text-based interface which required a considerable cognitive load just to learn to a point of basic functional understanding Macintosh took its own path.

It adopted a powerful processor that none of the competition was (yet) using and a relatively high-resolution screen of 512 by 342 pixels, which made the standard 300 by 200 display format seem hopelessly primitive. It eschewed crappy colours in favour of crisp black and white, and introduced a graphical interface consisting of windows and icons that resembled actual files and folders. It took the focus away from the keyboard and instead put it on the pointer a proxy for a hand or finger that was operated by a device called a mouse, which a user held in their hand and slid around the table. Whereas prior personal computers rendered all text in a single font, the Mac had different fonts and formatting styles, and documents actually appeared on the screen exactly as they would when printed on paper. And it made pull-down menus standard across the system so that basic operations could always be accomplished with ease even if a user forgot the keyboard command.

These features inspired people. As did the software that Apples engineers wrote to highlight them. Art and word processing applications MacPaint and MacWrite and the desktop-like Finder, together with the control panels and desk accessories that aided with smaller tasks defined not only a visual aesthetic but a whole design language. A new way of thinking.

Many of those who embraced this new paradigm accomplished incredible things. Just in the games space, they built the worlds first multimedia authoring tool, designed almost tangible interactive places in which the interface the barrier between player and world disappeared, and made adventures that captivated millions. They made games that looked like interactive cartoons or played like interactive movies. They crafted innovative first-person exploration and shooting games that broke boundaries in both technological and storytelling realms. They made games that presented such intuitive simulations of real-world or fantastical systems that they changed peoples lives.