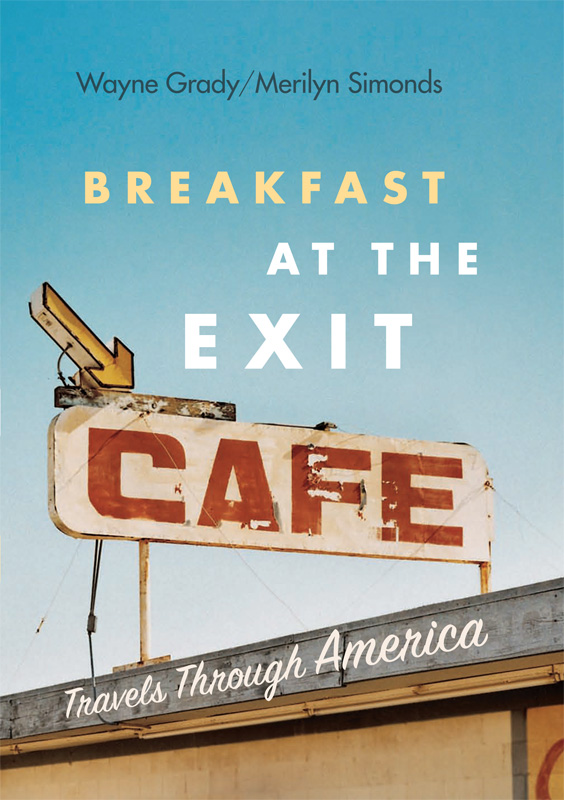

BREAKFAST AT THE EXIT CAFE

Travels

Through America

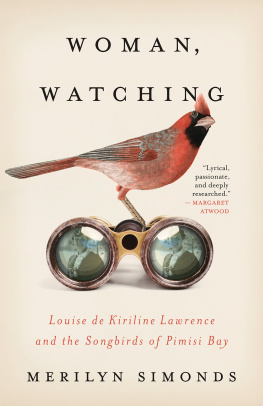

Wayne Grady / Merilyn Simonds

BREAKFAST

AT THE

EXIT

EXIT

CAFE

Copyright 2010 by Wayne Grady & Merilyn Simonds

10 11 12 13 14 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form

or by any means, without the prior written consent of the

publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing

Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver BC Canada V5T 4S7

www.greystonebooks.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-55365-522-0 (cloth)

ISBN 978-155365-656-2 (ebook)

Editing by Nancy Flight

Jacket and text design by Naomi MacDougall

Jacket photograph by Micheal McLaughlin/Gallery Stock

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Text printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer paper

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of

the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts

Council, the Province of British Columbia through the

Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada

through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Contents

W E didnt set out to write a book. We were in Vancouver, intending to drive back to Ontario in our green Toyota Echo, and we decided to take the long way home, down along the Pacific coast, across the southern states, then up the Atlantic seaboard. It was to be a holiday, an excursion. It was just before Christmas 2006, and we were keen to avoid driving across the Prairies in winter. We were naive. We were curious. We wanted to see the mountains of Washington and the forests of Oregon, the deserts of California and Arizona and New Mexico, the canyonlands of Utah, the arid farmlands of Texas, the troubled cities of Mississippi and Alabama, the exhausted plantations of Georgia and Virginia, the great, wind-beaten banks of the Carolinas. We thought this would be relaxing, a break from our writing lives.

We should have known better. Put two writers together in a car and keep them there for a couple of months, and its more than likely youll get a book. But what kind of book would it be? Both of us grew up, for the most part, in southern Ontario, close to the American border, although neither of us had travelled much in the United States. What we knew of America had come from America, not from our own experience of that country. We knew what Americans looked like and sounded like; we knew how they acted and sang and wrote. What we didnt know was what they were like at home.

We had no itinerary, no agenda. We didnt stick to the interstates, as Larry McMurtry did when he wrote Roads; we didnt drive only on smaller highways, as William Least Heat-Moon did in Blue Highways. The routes we travelled were blue and red and white and yellow on the maps, solid lines and dotted lines and sometimes no lines at all. We didnt tell anyone we were coming: we were neighbours who were dropping in unexpectedly, wanting only a cup of coffee and some conversation.

By the time we got home, we had driven more than fifteen thousand kilometres; travelled through twenty-two states; put on twenty pounds each; replaced half the car; slept in mom-and-pop motels, boutique hotels, dreary motor inns, the car; eaten in diners, cafes, bistros, five-star restaurants, chain eateries, food courts, the car. Our favourite meal of the day was breakfast, because eating breakfast every day in a restaurant is one kind of proof that youre on the road. And everyone else in there is travelling, too. Part of the reason we chose the title of our book is that the places we had breakfast took on for us a kind of iconic status. Like America itself, they became, for a time, our home.

John Steinbeck, in Travels with Charley, his book about driving the rim of America, wrote that people dont take trips, trips take people. He was right. This trip not only took us into America, into the heart of the neighbour we thought we knew, but also took us into ourselves. Throughout the book, Wayne speaks in his voicehis sections begin with Wand Merilyn speaks in hersM. The result is a conversation and a twinned meditation, too, as we each engage with the landscape were travelling through as well as our own interior geography.

We discovered that a marriage between two people is not unlike the sometimes uneasy truce that exists between two countries that have lain beside each other for a long time. We each came to that in our own way, and that, too, was part of the journey.

W ASHINGTON looms across the border from British Columbia at the end of a long line of cars and buses. As we await our turn at customs, we watch a man playing with his young son on the wide stretch of grass between two parallel roads, the one we are on leading into the United States and the other disappearing behind us into Canada. The man is tossing his son into the air and catching him on the way down, and the child is laughing hysterically, obviously frightened out of his wits. The man keeps throwing him higher into the air and catching him at the last minute, the boys head swinging closer and closer to the ground each time. We watch with resigned fascination until we arrive at a stop sign a few metres from the border, beside a placard that reads Canada This Way, with an arrow pointing behind us.

We are driving into America.

Border crossings always unnerve me, which, as Merilyn says, is an odd and tiresome thing, because I have crossed this and many other borders in my life and ought to know what to expect. I have no particular reason to expect to be unnerved. But to me, crossing a border is a harrowing experience, perhaps because I grew up in a border cityWindsor, Ontario, just across the river from Detroit, Michigan. The saying in Windsor was that the light at the end of the tunnel was downtown Detroit, and it was meant as a positive thing.

Every year before school started, my parents would whisk my younger brother and me through the tunnel to the United States because everything was so much cheaper on the other side. Theyd drag us up and down Woodward Avenue, into all the really cheap department stores, with their dark, uneven hardwood floors and sticky, glass-fronted cases, buying us cheap shirts and sweaters and pants and socks and windbreakers. At a designated spot between Woodward Avenue and the Detroit Tunnel, my father would pull the car over and my mother would frantically cut the price tags off all the pants with a pair of nail scissors, pull all the cardboard stiffeners out of the shirts, stuff all the bags and tags and cardboard and tissue paper and shoeboxes into one of the shopping bags, and toss the whole thing into a garbage pail practically within hearing distance of the customs shed. Then she would make us put on all the clothes wed just bought, to hide them from the customs official, who, if he spied an overlooked price tag or caught the whiff of new denim, would yank us from the car and make us take off all our clothes and then arrest my parents. In my family, duty was something one paid if one were caught wearing two pairs of pants.

Next page

EXIT

EXIT