ALSO BY TIMOTHY EGAN

The Good Rain

Breaking Blue

Lasso the Wind

The Winemakers Daughter

The Worst Hard Time

The Big Burn

Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher

The Immortal Irishman

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2019 by Timothy Egan

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

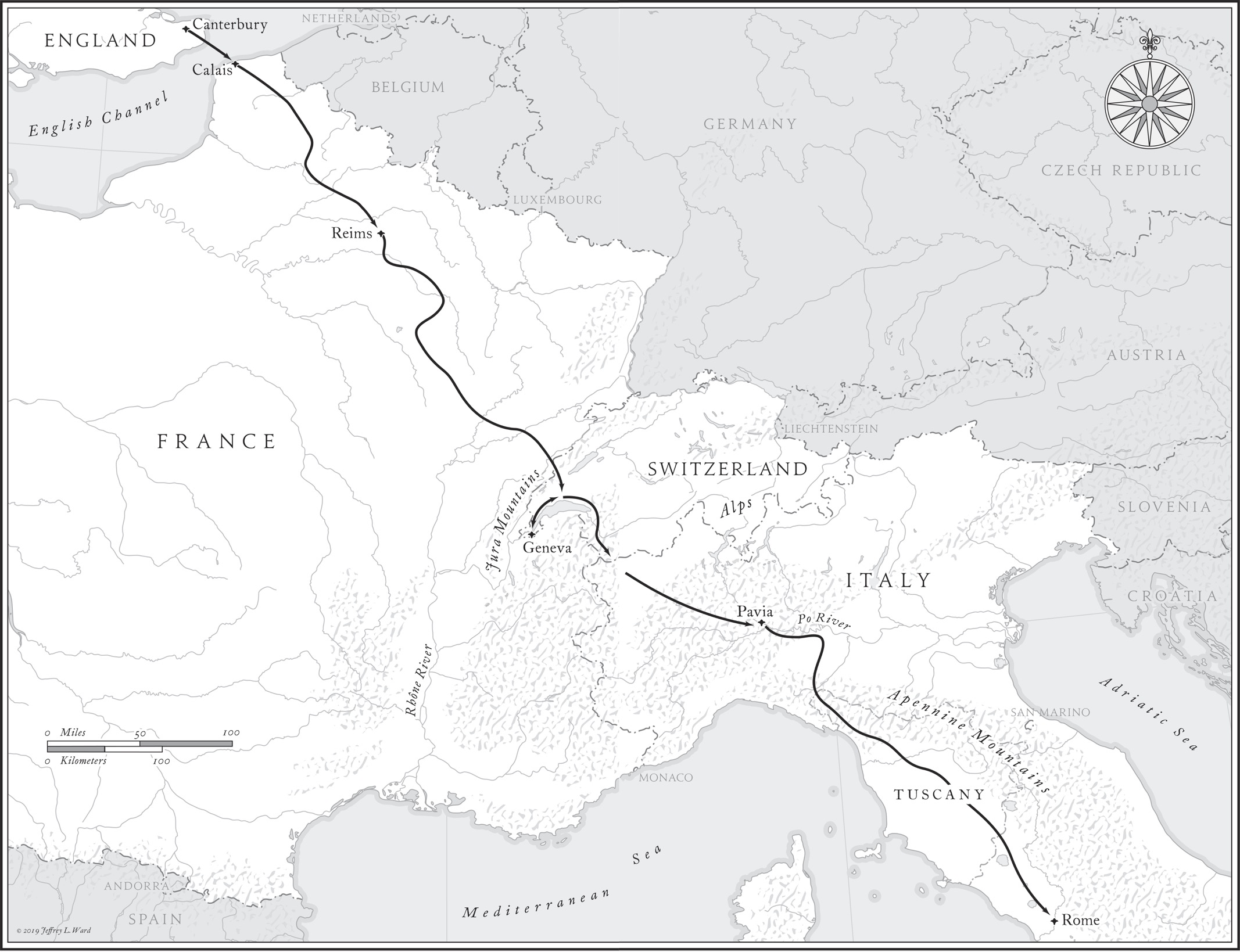

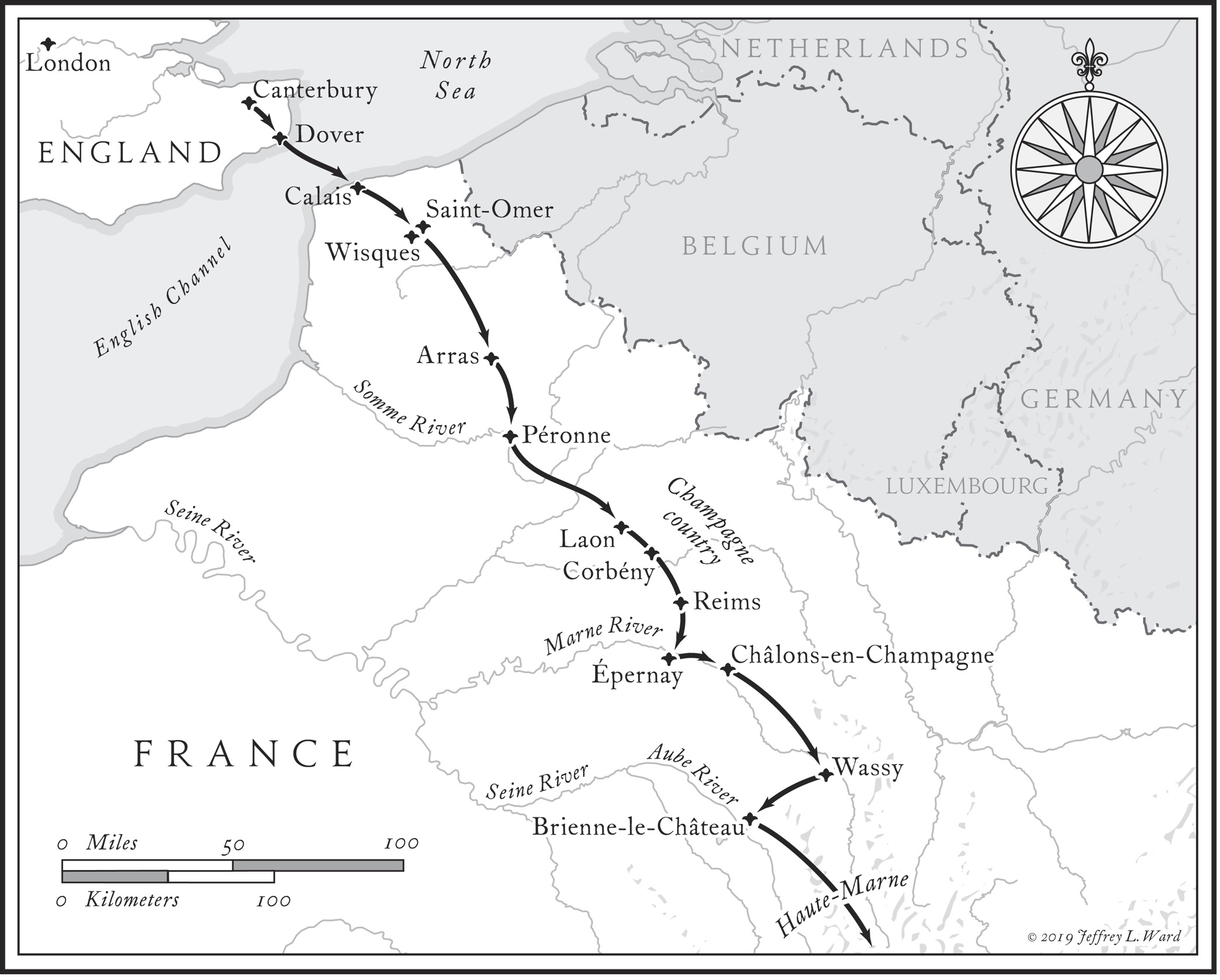

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-I N-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Egan, Timothy, author.

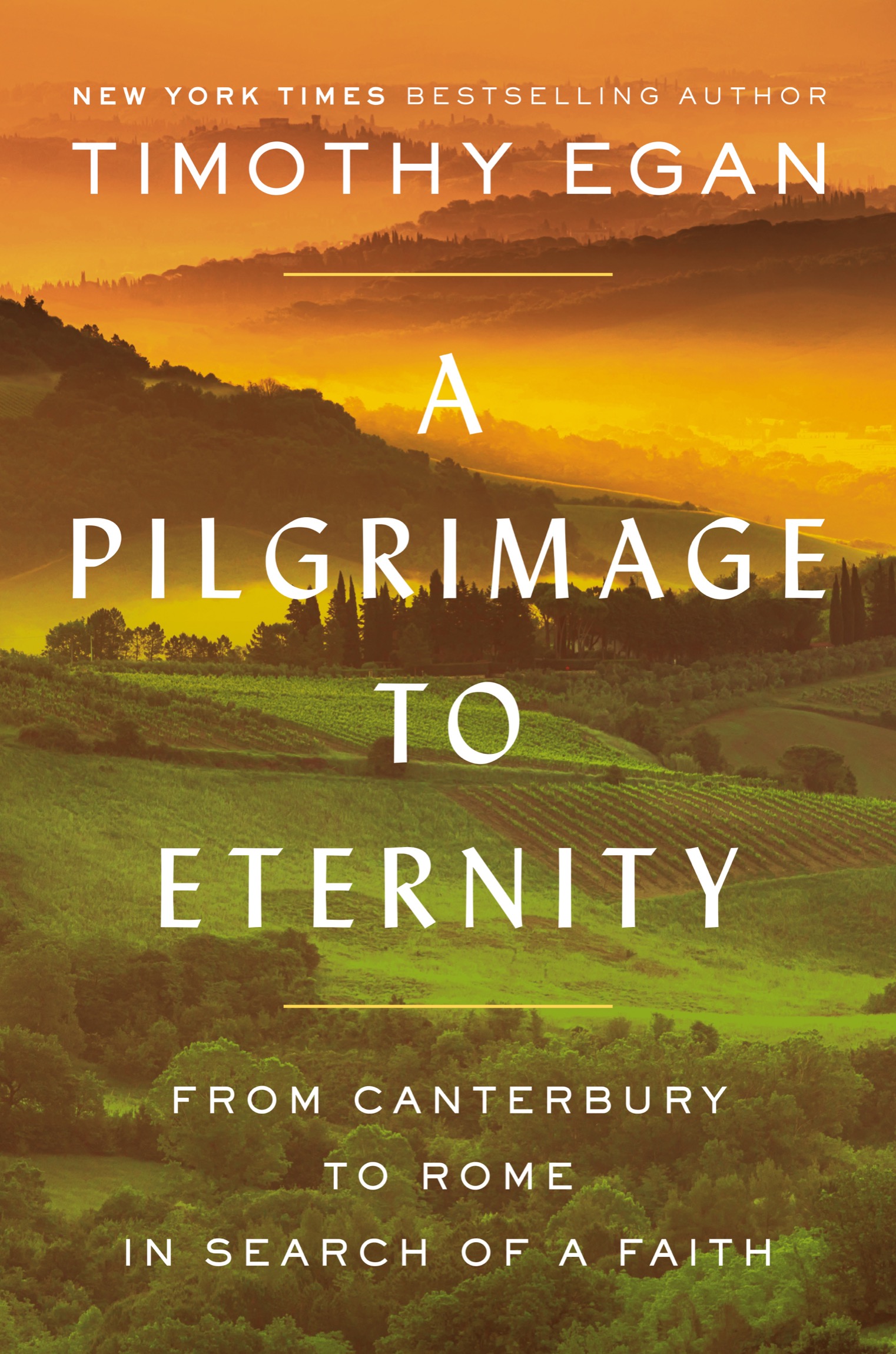

Title: A pilgrimage to eternity : from Canterbury to Rome in search of a faith / Timothy Egan.

Description: New York City : Viking, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019015599 (print) | LCCN 2019021460 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735225237 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780735225244 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Christian pilgrims and pilgrimagesEurope.

Classification: LCC BV5067 .E33 2019 (print) | LCC BV5067 (ebook) | DDC 263/.04245632dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019015599

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Cover design by Brianna Harden

Cover photograph by Evgeni Dinev / Shutterstock

Version_1

To my siblings: Maureen, Kevin, Mary Ann, Colleen, Kelly, Dan.

You can go home again.

CONTENTS

I

Q UEST

LAND OF KINGS AND ATHEISTS

ONE

LONDON FALLING

The passage to eternity begins on the Piccadilly Line to Cockfosters. Contain the snickering, you tell yourself during the gentle forward rocking through Londons Tube. By now, you should be purged of the trivial and juvenile. You should be in pilgrim mode. Youve prepared for a journey of more than a thousand miles by walking hills and stairs, by breaking in shoes and building calf muscles, by shedding weight and inconvenient thoughts. Youve tried to knead doubt into a lump of manageable anxiety. Getting in spiritual shape was much harder. You tidied up your affairs, made a donation to charity. Atoned. You ended a thirty-year feud with a man youve known since college. Although, when you told him all was forgiven, he responded with a quizzical look and said, Were we in a feud? You hope the soul has not gone dark. Youve given it a scrub, cleaned out the grime from long-held grievances, petty jealousies, and spells of intolerance. The goal is to be fresh, open to possibility.

At Heathrow earlier today, after a nine-hour flight from my home in Seattle, I felt inexplicably cheerful in the grim fluorescence of an international customs barrier, ready to roam.

Are you alone? the British officer asked. I wanted to say, Arent we all, but a sign warned that this was a gate of utter seriousness; it was a crime to joke.

Why are you alone?

I explained that I was starting a pilgrimage from Canterbury to Rome, the Via Francigena.

The what?

Well, surely youve heard of the Camino de Santiago in Spain, I told him. More than a quarter million people walk some part of that dusty path to the tomb of the Apostle Saint James every year. I will follow a less-known trail, once the major medieval route from Canterbury to Rome, the Via Francigena. The name means, roughly, the Way Through France, and is pronounced frahn-chee-jeh-na. More of a braid than a single road, it traces a course described by Sigeric the Serious, archbishop of Canterbury, when he walked through Europe to see the pope in the year 990. My plan is to travel the entire route of the Via, about twelve hundred miles on foot, on two wheels, four wheels, or trainso long as I stay on the ground. The Via Francigena crosses the English Channel to Calais, wends through dark towns still shadowed by King Clovis, Napoleon, and war, to hilltop cathedrals said to hold calcified scraps of saints and proof of miracles. It leaves the cold interiors of northern France for the revitalizing air of the mountains and the Reformation, deep into Switzerland. Up, up, up into the Alps after that. Down, down, down through the Sound of Music hamlets of the Val dAosta. Then south into the radiance of Tuscan villages first inhabited in the Etruscan era twenty-five hundred years ago. In the end, its a straight line to St. Peters Square over the fabled Roman road, in hopes of meeting a pope with one working lung who is struggling to hold together the worlds 1.3 billion Roman Catholics through the worst crisis in half a millennium.

N OW HER E IS my first stop, St. Pancras station in central London. Its another curious name, sounding like an homage to an internal organ. The tourist information booth has nothing on the origin. Some kind of saint. Pancras, it turns out, was a teenage martyr, killed by the Romans in AD 304 for refusing to worship one of their gods. The boy was beheaded. He has a special place in England because some of his relicsbody parts and the likewere carried to these shores in the first systematic attempt to bring Christianity to the island, in the sixth century.

The morning is lovely, May sunlight pouring through the big glass walls of the station. I pick up a couple of papers and magazines, happy to be in a city where print journalism is alive and shouting. Its tempting to overstate things in the daily grind of events, but the news of the day seems monumental on all fronts. Britain is cracking upan existential fight. Having shaped so much history for so many centuries, a fractious former imperial power struggles to find its place in the world, and with how much of that world to open its doors to. No nation is an islandeven one that is an islandentire of itself. A shared national narrative, difficult in the best of times, is far out of reach for this precious stone set in the silver sea, in Shakespeares perfect tribute.

And something else is running through the national disquiet: the kingdom is fast losing its belief in God. For the first time, more than half of all British say they have no religion at all. Some are looking for answers in the five-thousand-year-old Neolithic mystery of Newgrange in Ireland, a circular mound of tomb passages older than the Great Pyramids at Gizaa fascination of the neo-pagans. Others are dogmatically atheistic, if that isnt oxymoronic. In between are people who havent given up on the Big Questions, but are checking out of organized religion in droves. The collapse has hit the Church of England hard, with just 15 percent of UK residents now calling themselves Anglican, the faith founded by Henry VIII. To this day, the head of the church, ninety-three-year-old Queen Elizabeth II, is also head of state. For centuries, in order to hold office or even attend college, you had to take an oath of supremacy, swearing to the monarchs absolute power at the top of this nations established church.

ONE

ONE