Contents

Prologue

It was late afternoon when I reached the saints house. From a distance the building seemed hidden in mist. Closer I could piece it together: white walls, a low door, a tiled roof and shuttered windows. One of the shutters was loose, its catch bent out of shape. The room through the window was unlit, but I kept looking until the darkness came apart. A wooden chair leant against a wooden desk in the middle of the floor. Two crutches hung over the hearth, a giant rosary tied between them, its cross the colour of bone and each bead a knuckle. Dust on the floor, on the chair, the desk. Dust like vapour on the windowpane glass.

I tried the door and found it open. Inside the house was still, with a frosted, sour taste. A guestbook lay on the desk, the last entry dated eight months ago twenty names in childrens handwriting, from a school trip that visited in the spring. Under the book was a homemade board game, the pieces three model pilgrims, the board a winding road. Square number one was a drawing of this house. Fifty-five squares on was a box labelled Rome.

Signs were fixed to the walls, the printed card grey with damp. Here the saint helped his mother cook bread. There he played with his brothers and sisters. Upstairs was the room where he prayed.

Dropping my rucksack, I climbed the staircase. An attic ran the length of the house, with a brick chimney in the middle and bare cob at both ends. The roof tiles were bare too, the roof beams exposed. These beams were the same pale shade as the rosary downstairs, turning the attic into a skinned ribcage.

Past the chimney was a whitewashed alcove containing a cot with a chicken-wire mesh, a waist-high statue of a starved young man, and a stone slate engraved with the words Merci St Benot. The crucifix above the cot had Christ lying on his side with face serene, as if the cross were a bed and the body only resting.

Here the saint slept each night.

The previous evening, staying at the Abbaye Saint-Paul de Wisques, I had been told about this place the childhood home of the patron saint of pilgrims. When the brothers learnt I was walking to Jerusalem, they urged me to stop by. Now, standing in the saints bedroom, I tried to remember the rest of his story.

Benot-Joseph Labre was born midway through the eighteenth century. His father was a tradesman, his uncle a priest. His mother gave birth to fifteen children: five sons, five daughters, and five that never lived. The children were raised in Amettes, a farmers village seventy kilometres south of Calais. As a boy Benot-Joseph was quiet, devout, and at sixteen he decided to enter a monastery. But, when he went to the Carthusians at Longuenesse, they turned him away. The Cistercians at La Trappe did the same. He was too young, they said. Too frail. He did not know plainsong. He had not been taught philosophy. The boy wanted to withdraw from the world, yet every time he tried it ended in failure. Instead, he cast himself out.

Aged twenty-one, Benot-Joseph left home, promising to return for Christmas. His mother, his father, his brothers and sisters none of them saw him again.

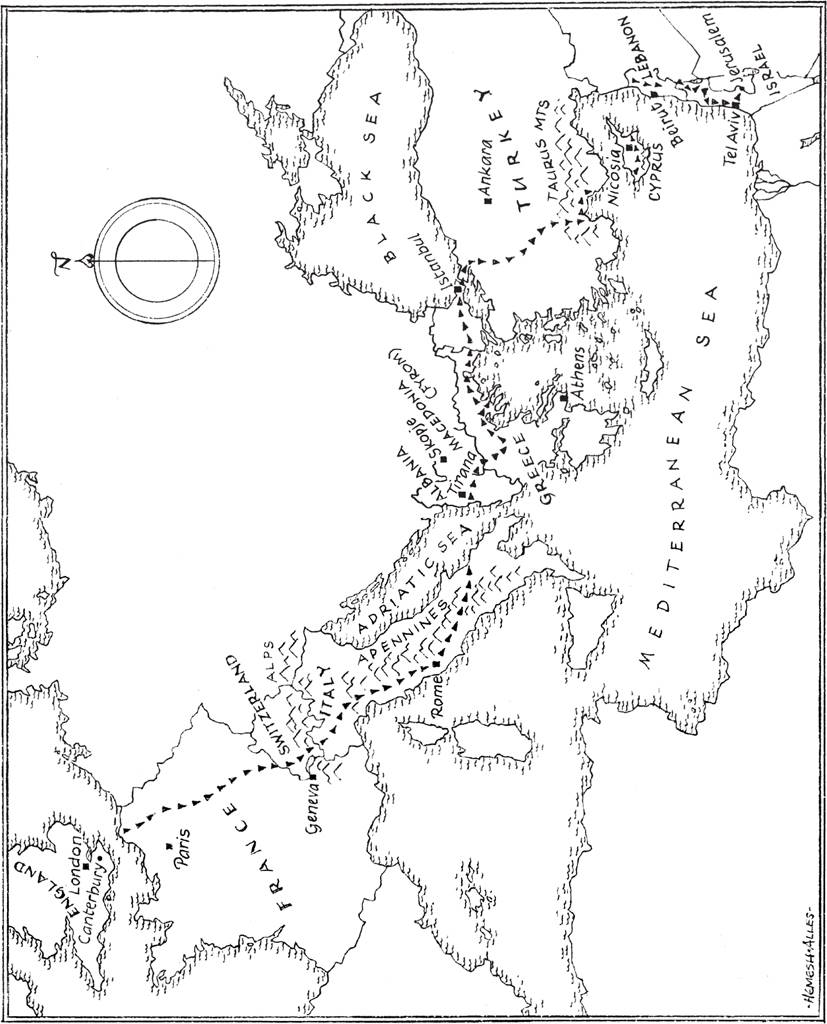

For the next seven years he wandered Western Europe. This was the early 1770s, and the pilgrim tracks that once connected the continent had fallen into disuse. Benot-Joseph Labre lived nearer to an age of steam than an age of sacred travel, yet he journeyed on foot between Einsiedeln and Rome, Loreto and Santiago de Compostela. The boy too weak for the monastery covered thirty thousand kilometres with no money in his pocket and no cloak for his back.

His days were endless hardship. He ate dry bread or the herbs that grew wild by the roadside. He slept on the ground or, when offered a roof for the night, refused a bed and slept on the stairs. Imitating the Fools-for-Christ those medieval mystics who behaved like lunatics and animals Benot-Joseph made himself wretched for fear of pride. According to his confessor, Fr Marconi, this humility was born of love. The pilgrim so loved his fellow men that he hoped his austerities might atone for their sins. But was it love that first pushed him away from home? Looking at the cot where he slept, I could think of another reason. Ever since he was a boy, Benot-Joseph had dreamed of life in a monastery. The adult world rejected him, thus he decided to live always as a child, a pilgrim Peter Pan.

Well, perhaps. Or perhaps I wanted the saints journey to explain my own somehow. For Benot-Joseph Labre was the patron not only of pilgrims, but also of vagrants, unmarried men and the mentally ill. And, standing in his bedroom that afternoon, I felt his story had something to teach me.

The alcove was dim now, and there was not one sound in all the house. No creaking doors, no heaving floors, the whole place made mute by dust. Yet I had a vague sense that I was no longer alone here, so I left the attic and ducked down the stairs. Then I slipped out into the mist.

My first pilgrimage started on a midsummer morning six months earlier. I set off from the flat where I was living in London, followed the Thames east, and joined the medieval route to Canterbury. It was a surprising thing to do, as for much of the year I had been afraid to leave my room.

When I was twenty-three I had a nervous breakdown. Afterwards I was frightened of the city, of lunchtime crowds and rush-hour trains and the angry, anxious streets. I went to work and sat senseless at my desk. I went to doctors and psychiatrists, counsellors and therapists. Otherwise I lay in bed, turned from the window, my thoughts hurting.

One year on, the fear was lifting. In early summer I was taken off antidepressants. As the days got warmer, I wanted to go outside, and that June I decided on a walk. Canterbury was a whim the walk at the beginning of English literature. The forecast was good, meaning I did not think to bring a waterproof jacket. Or buy maps, trusting my phone instead. That Wednesday was the solstice. Perfect.

Everything went wrong. For two days I marched from dawn until dusk, covering almost a hundred kilometres a grim total for someone who last hiked at school. On Tuesday I went so far off course that I had to catch a train to my hostel. On Wednesday I was soaked and sunburnt in the space of an hour, and spent the entire afternoon trudging down the A2, eyes harsh from exhaust fumes. When I got to Canterbury my heels were bruised and my socks clotted with blood. Yet I do not remember the pain. I remember lying on the grass beneath the cathedral, watching the daylight last into night, with a sense of relief so complete it was like healing. For a long time my world had been closing in, smaller and smaller, until it was no bigger than a cell. Walking made the world wide again.

A figure carrying a staff and scrip was etched onto a stone by the cathedrals southern porch. Around him was written, La Via Francigena / Canterbury Rome. At that point I knew nothing of the holy road to St Peters, but as I lay on the grass an idea took shape in my mind. Why not keep walking? Why not leave England and walk to Italy? And then keep going, to the edge of Europe, on and on to the worlds most sacred city.

The following day I learnt what I could about the Via Francigena. One website listed the names it had been known by: Lombard Way, Frankish Way, Chemin des Anglois, Via Romea. A second website listed the Anglo-Saxon kings who travelled its length Caedwalla and Coenred, Offa and Ine as well as Alfred the Great and King Cnut. A third explained how, in the year 990, the Archbishop of Canterbury also travelled the Via Francigena, to collect his pallium from the pope. On the return journey a scribe noted every town and city where they stopped. An image of that manuscript showed a page of numbered Latin names, some of which I recognized: