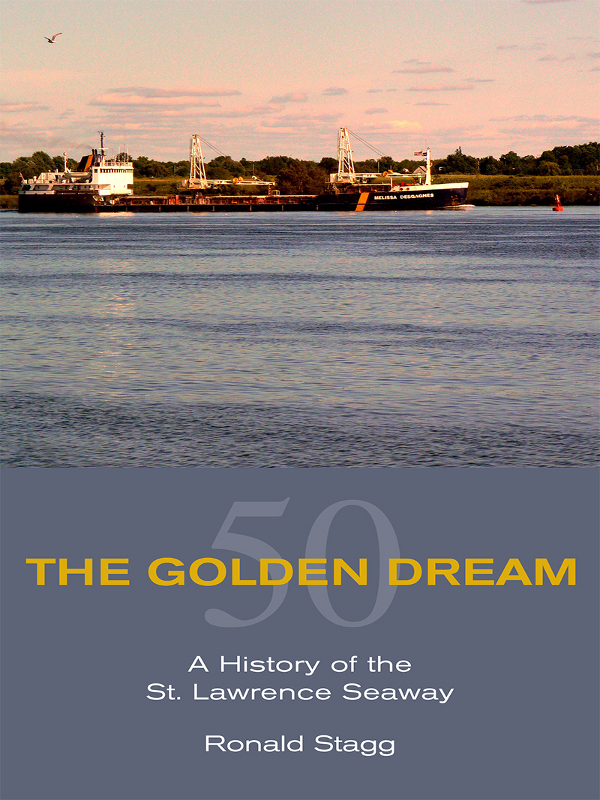

THE GOLDEN DREAM

THE GOLDEN DREAM

A History of the

St. Lawrence Seaway

Ronald Stagg

Copyright Ronald Stagg, 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Editor: Allison Hirst

Design: Courtney Horner

Printer: Transcontinental

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Stagg, Ronald John, 1942-

The golden dream : a history of the St. Lawrence Seaway / by Ronald Stagg.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-55002-887-4

1. Saint Lawrence Seaway--History. I. Title.

FC2763.2.S715 2010386'.509714C2009-900304-X

1 2 3 4 514 13 12 11 10

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and The Association for the Export of Canadian Books, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit program, and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

Published by The Dundurn Group

Printed and bound in Canada.

www.dundurn.com

To my parents,

who introduced

me to the Seaway.CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Age of the Innovators: The

Early Canals, to 1848 - Chapter 2 The Age of the Engineers: The

Later Canals, to 1932 - Chapter 3 Whose Dream? Negotiating the

Building of the Seaway - Chapter 4 Building a Dream: Seaway

Construction - Chapter 5 Reassessing the Dream: The

Seaway in Operation - Epilogue A Trip Through History: The

Canals Today

I was quite intrigued when I was asked by the publisher Dundurn Press to write a book on the history of the various St. Lawrence canals and their competitors to mark the 50th anniversary of the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway. I have had a long and diverse association with the subject.

My first exposure to the St. Lawrence Seaway was as a young teenager in 1956 when my parents took me on a road trip to the Maritime provinces. This was before the days of superhighways, expressways, and thruways, and accommodation was usually in cabins, hotels (sometimes railway hotels), or privately built motels. Our first day was spent driving on Highway 2 from Toronto to Kingston, a trip which now takes less than three hours but at that time took most of the day as we meandered through towns and villages and large swaths of rolling farmland. On our second day we drove much of the way along the shore of Lake Ontario, travelling through more towns and villages. My father explained that this area was going to be flooded and that many of the buildings would be moved or demolished. We passed the old cut-stone canal at Cardinal and ate lunch beside the canal at Iroquois. It seemed as if you could reach out and touch one of the "14-footers," those unique ships specially built to haul freight from Prescott, through the narrow canals, to Montreal. We saw a building being moved, a rather rare sight at the time as house-moving was in its infancy. We undoubtedly passed the Long Sault Rapids also, famous to generations of travellers on the river, but I have no memory of them.

I have returned to the area many times since, either to visit Upper Canada Village, a collection of salvaged buildings judged to be of architectural and historical merit and arranged in the form of a village to portray life in the early nineteenth century, to explore the Lost Villages Museum, a collection of minor buildings from several villages that no longer exist, or to camp on the Long Sault Parkway. The latter is built on the tops of hills that rise above the flooded farms, connected by a series of causeways. Here one can see the beginning of walkways that no longer exist that once led to houses that no longer stand; a rather surreal experience is seeing the old Highway 2 rise out of the water, cross the high ground, and disappear into the water on the other side. An outdoor presentation centre marks the site where divers can descend to the lock of the original canal that used to be located near the Long Sault Rapids. This now lies some 50 to 60 feet below the surface of the water. Some nights, camping on the parkway, the throb of ships' engines and propellers approaching the canal on the American side about a mile away is enough to wake campers from a sound sleep. At Cornwall, while crossing the high-level bridge to the United States, one can look down on the remains of the old Cornwall Canal which lead to a dead end near the massive dam and powerhouse - major features of the St. Lawrence Seaway.

In the 1990s I helped friends bring a sailboat from Albany up through the Erie and Oswego canals, early competitors for the St. Lawrence route, to Lake Ontario. I had long been curious about the first of these, an early North American canal. It turned out not to be the waterway of my imagination. Officially renamed the New York Barge Canal years earlier, it no longer ran along its original route for its whole length, serving towns and cities along the way, and it was wider and deeper than the original. It was a wonderful trip, nevertheless, as much of the canal runs through rural New York State. We passed and sometimes stopped at waterside inns, travelled long distances in which trees hanging over the water obscured most of what lay beyond, making it seem like we were in another century, and saw the remains of factories once served by the canal. Partway up, in one bucolic setting, a sign on the shore pointed to the remains of locks from the original canal. Shallow and narrow, these were suitable only for small barges pulled by horses. On the way home from Oswego to Toronto by bus, a street name in Syracuse indicated the path of the original canal before it was rerouted in the late nineteenth century.

My association with the Ottawa-Rideau route from Montreal to Lake Ontario has been somewhat episodic, crossing it by car or on foot rather than travelling it by boat. Skating on the canal during winter in Ottawa is the closest thing to being on the water that I have experienced. From the step locks beside the Parliament Buildings, where the Rideau begins (a site seemingly more appropriate to a European city than to the capital of a North American country), to the industrial remains beside the locks at historic Merrickville (once an important spot along the Rideau Canal, but now more an attractive bedroom community for those working in Ottawa), to viewing the canal at Smiths Falls or at rural spots beside the highway, one has a sense of what it is like to travel the canal. The scenery alongside the canal is generally so attractive that it conveys no sense of the horrendous conditions encountered by the labourers who constructed it in the early nineteenth century.