This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

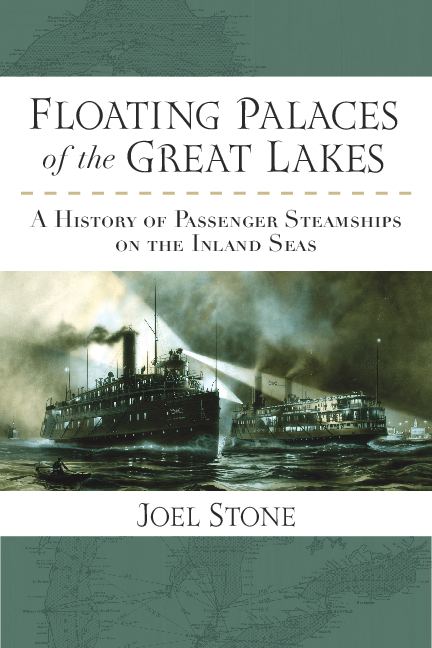

Floating palaces of the Great Lakes : a history of passenger steamships on the inland seas / Joel Stone.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-472-02831-3 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-05175-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-07175-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Passenger shipsGreat Lakes (North America)History. 2. Lake steamersGreat Lakes (North America)History. 3. Steam-navigationGreat Lakes (North America)History. I. Title.

T here is a romanticism associated with the steamboat era on the Mississippi River that flows through the American consciousness. Be it the popularity of Mark Twains beloved literature or the grandeur of the lush Broadway musical Showboat, there is little doubt that steamboat gothic conjures visions of antebellum riverboats and an elegant and relaxed form of travel.

Across North America this romantic sentiment has not translated to an equally iconic steamboat era on the Great Lakes. Yet, by nearly every measure, steamboats that plied the lakes were the true passenger palaces of North Americas maritime. There were commercial similarities among the western competitors, but Great Lakes vessels were more versatile and robust than riverboats, designed to operate well on open waters as well as in river currents. Against eastern competitors, Great Lakes shipyards laid claim to the largest and most luxurious vessels to participate in any coastal passenger trade. Nowhere in the world was there a concentration of ships defining engineering advancement, customer satisfaction, and geographic opportunity as on the Great Lakes.

There exists a curious gap in the historic literature about this commercial niche. The body of material related to this topic is generally dealt with through various studies of transportation, immigration, labor relations, and so on. Herein a multifaceted story is presented in depth, covering nearly 150 years. However, it is not the intention of this volume to identify every vessel or rectify all arguments and omissions in the record. Instead, this narrative portrays the passenger ship industry on the Great Lakes through its growth, prosperity, and demise.

Boats have been part of my consciousness for as long as Ive been aware. Of three memories prior to my third birthday, one involves a boat: my uncles Chris-Craft runabout on Lake Charlevoix in northern Michigan. I would like to say that I remember the South American cruising past a family picnic on Belle Isle, near the neighborhood where I grew up on the east side of Detroit, but its too hazy to claim as fact. However, the parade of ships that passed our picnics certainly impressed on me the fact that I lived in a seaport town.

My affinity for the water, which in my family began generations ago, is most easily traced to an Irish sailor and fisherman who moved his brood to Nova Scotia and was afterward lost on the Grand Banks. Two generations later I had a grandfather, Maurice Lagrou, who was a professional photographer. He grew up on the Detroit River and swam around Belle Isle on a bet. Later in life, he took Peshaesque photographs and very early moving pictures of vessel traffic on the St. Clair River. My other grandfather, Ferris Stone, was part owner of a small sailing schooner that competed in early Bayview Yacht Club races to Mackinac Island. My parents, Fred and Lenora Stone, brought this appreciation of water together, and their three children absorbed it in varying degrees. I seem to have been the most smitten.

When growing up, I was fortunate to live a mile or so from Lake St. Clair, the pass-through pond between lakes Huron and Erie. The city of St. Clair Shores claimed more registered recreational boats than anywhere on the continent. Sleepy, foggy summer nights meant steam whistle signals floating in off of the Detroit River. I was not very good at fishing, but my best friend Mike had older brothers who talked their dad into buying a sailboat, and we enjoyed that sloop to its fullest. My coming-of-age had a lot to do with sailing.

I considered joining one of the sea services but came no closer than a stint as disc jockey on the Bob-Lo boat Columbia, a daytime excursion ferry between Detroit and an island amusement park. Cool job. I got my Coast Guard papers.

I began to understand maritime history and the depth of the literature when I studied with Father Edward Dowling, an engineering professor at the University of Detroit and an avocational marine historian and artist. His personal collection of data and ephemera was vast, and I came to understand that there were similar collections in libraries, museums, and homes throughout the Midwest.

In putting together this acknowledgment, so many instructors, mentors, and partners come to mind. To mention a few does a disservice to the many, but inevitably there are the Miss Spoors and Mr. Baileys who encouraged writing and the Father Dowlings and Pat Labadies who loved the boats. Together with Denver Brunsman and Doug Fisher, I came to understand how a book was molded and learned to embrace the challenge when the opportunity presented itself.

The friends I have sailed with add flavor to every word that follows, remembering sloops named Phoenix, MicJay, Aegir, Quicksilver, Aggressor, Patriot, and, with most affection, Sean Cra, Conundrum, the Cal-25 Christmas, and her longer, more comfortable sister, White Christmas. The best way to know the lakes is to sail them, and Ive been fortunate to see most of them from deck level. To all who made that possible and enjoyable, I am grateful.

Throughout this volume an attempt is made to recognize the people who contributed significantly to the historical record regarding passenger steamships or to the ability of historians to access those records. In many cases, these gentlemen and ladies also encouraged my pursuit of this topic, whether they knew it or not. Patricia Majher, editor of Michigan History magazine, and Dedria Cruden sparked this project. The staff of the University of Michigan Press has made this process a pleasure, notably Scott Ham and Kevin Rennells, who shepherded the manuscript through the gauntlet. Mary Peterson created a thorough index that future researchers will gratefully leverage. And once again my friend Doug Fisher coached the prose, returning it to within the bounds of accepted grammatical norms.

This chronicle leveraged decades of dedication by innumerable scholars. A few writers deserve note. Transportation historian George Hilton, formerly Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of California, Los Angeles, wrote extensive on various aspects of Great Lakes steamship travel. His analysis of the Lake Michigan passenger industry remains the finest compendium related to that regional business. Likewise, the work of Francis Duncan on the Detroit & Cleveland Steam Navigation Company (D&C) and its associated firms, serialized in