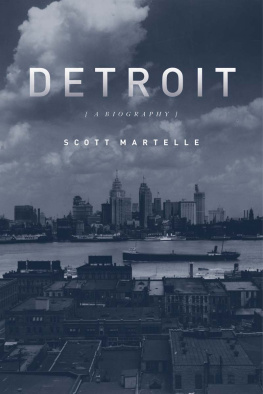

DETROIT WAS ESTABLISHED as a French settlement three-quarters of a century before the founding of this nation. A remote outpost built to protect trapping interests, it grew as agriculture expanded on the new frontier. Its industry took a great leap forward with the completion of the Erie Canal, which opened up the Great Lakes to the East Coast. Surrounded by untapped natural resources, Detroit turned iron from the Mesabi Range into stoves and railcars, and eventually cars by the millions. This vibrant commercial hub attracted businessmen and labor organizers, European immigrants and African Americans from the rural South. At its mid-20th-century heyday, one in six American jobs were connected to the auto industry, its epicenter in Detroit. And then the bottom fell out.

Detroit: A Biography takes a long, unflinching look at the evolution of one of Americas great cities, and one of the nations greatest urban failures. It tells how the city grew to become the heart of American industry and how its utter collapsefrom 1.8 million residents in 1950 to 714,000 only six decades laterresulted from a confluence of public policies, private industry decisions, and deep, thick seams of racism. And it raises the question: when we look at modern-day Detroit, are we looking at the ghost of Americas industrial past or its future?

Copyright 2012 by Scott Martelle

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-56976-526-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Martelle, Scott, 1958

Detroit : a biography / Scott Martelle. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-56976-526-5 (hardcover)

1. Detroit (Mich.)History. 2. Detroit (Mich.)Economic conditions.

3. Detroit (Mich.)Population. 4. African AmericansMichiganDetroitHistory. I. Title.

F574.D44M37 2011

977.434dc23

2011041173

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For Margaret.

And for Detroiters, past and present, who are fighting for its future.

CONTENTS

Detroit is especially noted for its broad and cleanly streets, its wide and well-kept walks, its numerous and thrifty shade trees, its extensive and beautiful lawns and gardens, the number and attractiveness of its parks and public squares, the varied and tasteful architecture of its residences, the stability of its mercantile life, and the range and extent of its manufacturing interests.

Guide to the Streets, Street Pavements, Street Car

Routes and House Numbers of Detroit, 1901

PREFACE

The grand dreams of Detroits many pasts are clustered here in the heart of downtown, bookended by the termini of the John C. Lodge and Walter P. Chrysler Freeways. The roads end a half mile apart, the Lodge at West Jefferson Avenue and the Chrysler at East Jefferson Avenue, and for a couple of generations now they have linked the regions sprawling suburbs with the citys downtown heart. Given Detroits economy, which has seized up like an engine run dry, its hard not to see those worn and potholed freeways as metaphors. Arteries carrying shrinking loads. Aspirations that fell short. The distance between what is and what might be. Or what once was.

Theres a history behind the names. Chrysler, of course, helped build Detroit into the center of the automotive world. The Lodge Freeway is named after a pre-Great Depression mayor who moved to politics from the city desk of the Detroit Free Press newspaper. Midway between them lies a parallel thoroughfare, Woodward Avenue, a psychological dividing line separating east from west while physically connecting the northern suburbs beyond Eight Mile Road to the riverfront. The avenuea grand boulevard, really, at six lanes wide in placesis the legacy of Augustus B. Woodward, appointed in 1805 by his friend, President Thomas Jefferson, as the first chief justice of what was then the Michigan Territory.

The timing was crucial to creating the Detroit we know today. Woodward arrived in Detroit less than three weeks after most of the small frontier town had burned to the ground, and he assumed for himself the task of redesigning the city, the first of many attempts at a renaissance, by borrowing Pierre Charles LEnfants hub-and-spoke vision for the nations capital. In a display of hubris, Woodward named Detroits new central artery after himself, joking later that he intended nothing more than to reflect its direction from river to woods. Woodward also named the road running parallel to the river (and following an active Indian trail) after Jefferson, and over the next two centuries Woodward Avenue became the citys defining corridor while Jefferson Avenue gave rise to the early industries that defined Detroits niche in the world.

These and other roadways, and the men after whom they are namedChrysler, Ford, Fisher, Jeffries, Reutherrepresent different slices of Detroits past, and each in its way played a significant role in the citys evolution from forest to factory, boom to bust, and dawn to dusk. I lived in Detroit for a decade in the 1980s and 1990s, spending most of it as a staff writer for the Detroit News, whose offices still stand a few blocks northwest of the intersection of Woodward and Jefferson. And it was as a journalist that I first came to see this spot as the nexus of many thingspast and present, river and land, wealth and poverty.

Just to the east of the intersection stands the Renaissance Center, the iconic vertical tubes that Henry Ford II had built in the 1970s hoping they would, indeed, spark another renaissance in this once-great city. The RenCen, as its called, defines Detroits skyline as much as the Empire State Building defines New York Citys. Downriver, to the west, stands the Veterans Memorial Building at Hart Plaza, roughly on the site of the original 1701 French settlement that evolved into present-day Detroit. Nearby, on a traffic island at the intersection of Woodward and Jefferson, a twenty-four-foot-long arm ending in a giant clenched, black fist dangles horizontally from a four-legged pyramid frame, like those that backyard mechanics use to suspend engines theyve lifted out of cars. Known locally as The Fist, the statues formal name is the Joe Louis Memorial, recognizing the larger-than-life boxer who came of age in Detroits old Black Bottom slum. Louis was a black hero in an era in which black heroes, and black celebrities, were forced into small orbits ancillary to most of American life. Louis, a punching machine, broke through that barrier, and its fitting that a reproduction of a powerful and successful black mans fist stands here in the arrhythmic heart of the city. It was designed by Los Angeles sculptor Robert Graham, on commission from Sports Illustrated, as a gift to Detroit. Graham chose to cast a fist instead of the whole fighter because, he said, he wanted to focus on the core element of Louiss fame, and leave the monument open to interpretation. He never addressed whether he chose to leave the boxers fist ungloved as a bit of artistic subterfuge, but that is how it has been takena play on the Black Power salute anchoring one of the citys key intersections.

In October 2009, just down the street from The Fist, the full weight of Detroits modern decline played out in a moment of poignant drama. As the nation struggled with the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, the City of Detroit decided to use $15.2 million in federal economic stimulus money to help 3,500 city residents stave off eviction or, if homeless, help them pay for housing. Given the citys pervasive poverty and the auto industrys financial crisis, city officials expected a lot of interest in the program. So they set up a room in Cobo Hall, the citys 2.4-million-square-foot riverfront convention center, to handle the rush for applications. Still, they werent prepared for the flood of desperation. Propelled by false rumors of a cash handout, some fifty thousand people showed up looking for help, many spending the night on the sidewalk in a sprawling, brawling mass.

Next page