ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book could not have been completed without the interest, generosity, and assistance of many individuals. For their encouragement, time, information, artifacts, and photographs, I owe a great debt to Mike Montgomery, Nan Bostick, Charlie Rasch, Rudy Simons, Duncan Schiedt, Josh Duffee, Arthur LaBrew, Robert Essock, Stan and Steve Hester, Matt Lee, Evan Milan, Greg Hathaway, Chris Smith, Romie Minor, and the E. Azalia Hackley collection.

For technical assistance, I would like to thank Durwood Coffey for his tireless hours of scanning and preliminary art direction. For their proofreading, advisement, and encouragement, I would like to thank Christine Schinker, Dorrie Milan, Rudy Simons, Nan Bostick, Arthur LaBrew, Mike Montgomery, Charlie Rasch, James Dapogny, Mike Karoub, Emily, Benjamin and Evan Milan, Brian Delaney, Scott Clauser, James Meeker, Janet Pecot, V. Thomas Adams, Jeff Sizemore, and Greg Hathaway.

Due to space considerations, many of the attributions appearing in captions have been shortened or abbreviated. In order to provide full credit to the sources, I would like to list the sources requiring a more formal attribution in their complete form here. Photographs that are attributed to the Hackley Collection have been provided courtesy of the E. Azalia Hackley Collection of Negro Music, Dance and Drama, Detroit Public Library; items attributed to the Montgomery archive are courtesy of Michael (Mike) Montgomery; and items attributed to the Hester collection are courtesy of Stan and Stephen Hester. All other parties are named appropriately, and my great thanks and appreciation to all of these individuals. All images without attribution are from the authors collection.

I dedicate this book to my brother Phillip B. Milan (19501987), who bought me my first Scott Joplin record when I was 11 years old; to my mother Ann A. Milan (19261999) and my father Gayle L. Milan (19242004), who suffered through years of my early, at times seemingly incoherent, piano banging and spent countless hours with their eccentric son while he poured through piles of old sheet music and records; and to Charlie Rasch, my mentor, who showed me how the piano should be played and introduced me to Mike Montgomery, Stan and Steve Hester, Bob Seeley, Dave Wilborn, Kate and Warren Ross, Howard Rasch, and Martha Sewellsome of greatest people I have ever come to know.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bjorn, Lars, and Jim Gallert. Before Motown: A History of Jazz in Detroit, 19201960 . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Blesh, Rudi, and Harriet Janis. They All Played Ragtime . New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1950.

Bostick, Nan, and Dr. Nora Hulse. Ragtimes Women Composers: An Annotated Lexicon. Ragtime Ephemeralist 3 (2002).

Bostick, Nan, and Arthur R. LaBrew. Harry P. Guy, and the Ragtime Era of Detroit, Michigan. Ragtime Ephemeralist 2 (1999).

Bostick, Nan. Meet Uncle Charlie. Rag Times 32, no. 3 (1998).

Charters, Samuel B., and Leonard Kunstadt. Jazz: A History of the New York Scene . Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1962.

LaBrew, Arthur R. The Detroit History Nobody Knew . 2 vols. Detroit, MI: self-published, 2001.

Rust, Brian L. American Record Label Book . New York: Da Capo Press, 1984.

. Jazz Records, 18971942 . London, England: Storyville Publications, 1983.

Sudhalter, Richard M., and Phillip R. Evans. Bix, Man and Legend . New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1974.

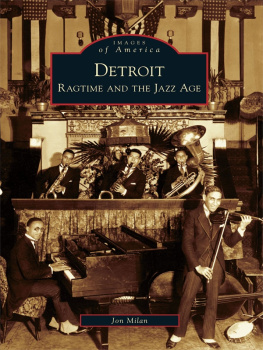

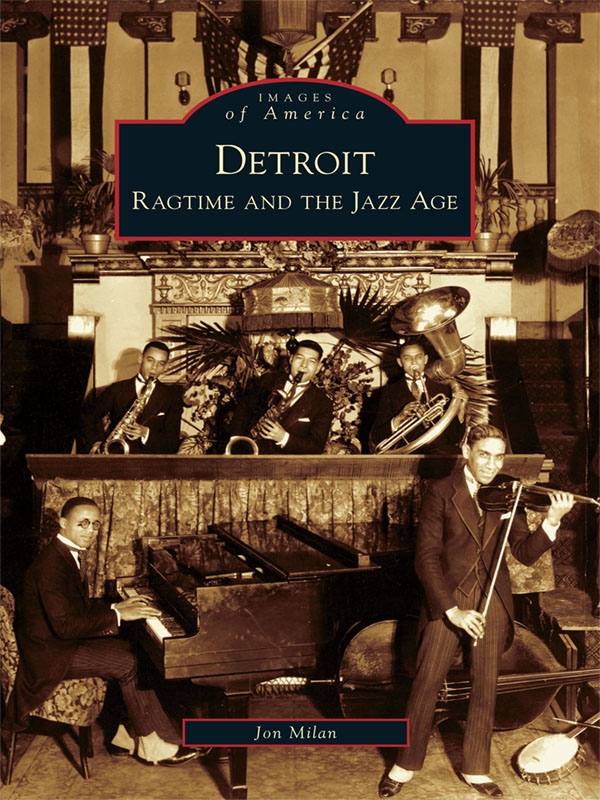

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

ECHOES FROM THE SNOWBALL CLUB

During the short span of time between the Civil War and 1900, the country entered into an accelerated age of innovation and technology that introduced practical electric lighting, the telephone, recorded sound, automated music machines, and the automobile. Late in those years, almost without notice, the music that drifted out from the smoky doorways of dance halls, saloons, and brothels began to take on new characteristics. It had a lilting swagger and sway and was played in what they called ragged time. Before long, hints of it were evident in the songs and tunes played by the song pluggers, street musicians, and local dance bands. It was there before it had a name, and suddenly, it was everywhere.

Ragtime is a genuine American creation, an American musical synthesis. Rhythmically and melodically, it owes much to traditional African American dances and songs; its influences can also be heard in the folk melodies of the Eastern European Jew; structurally and harmonically it is heavily seated in Western European tradition. In America at the end of the 19th century, wherever a mixture of these influential populations thrived, ragtime music was in a strong state of development.

One bustling center of this type was in and around Kansas City, Missouri (most notably Sedalia), generally considered the center of the ragtime universe. Other population centers were also active in the development of ragtime music at the time. The fact that Detroit would come to play a significant role in the development of this distinctly American music can be attributed to key factors in its geographic, political, and demographic history.

In the 19th century, European immigrants flocked to Detroit, an up-and-coming city surrounded by commerce-friendly waterways and rich farmland. For African American fugitive slaves, it represented even morefreedom from bondage.

Michigan was a hotbed of abolitionism and a major artery of the Underground Railroad. During reconstruction, many more African Americans migrated north, seeking opportunity in a friendlier, economically sound environment, and rounded out the ingredients that would make Detroit ripe for ragtime development.

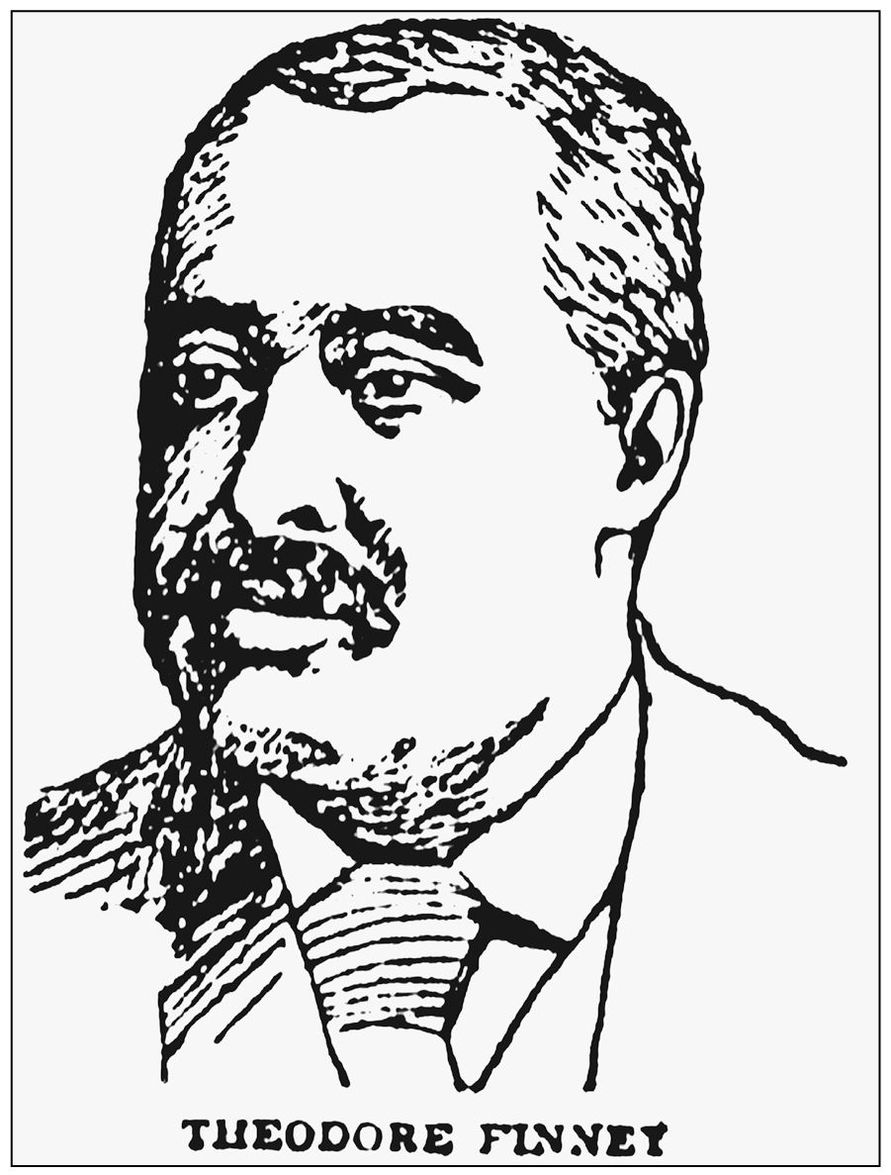

THEODORE J. FINNEY (18371899). Born in Columbus, Ohio, African American musician and bandleader Theodore J. Finney migrated to Detroit in 1857. He was an accomplished violinist, possessing strong leadership skills and a keen business acumen. Accompanying him was fellow violinist and business partner John Bailey. Together they established the Bailey and Finney Orchestra, which quickly became one of the most popular and sought-after musical contingencies in the city. (Courtesy of the Arthur LaBrew collection.)

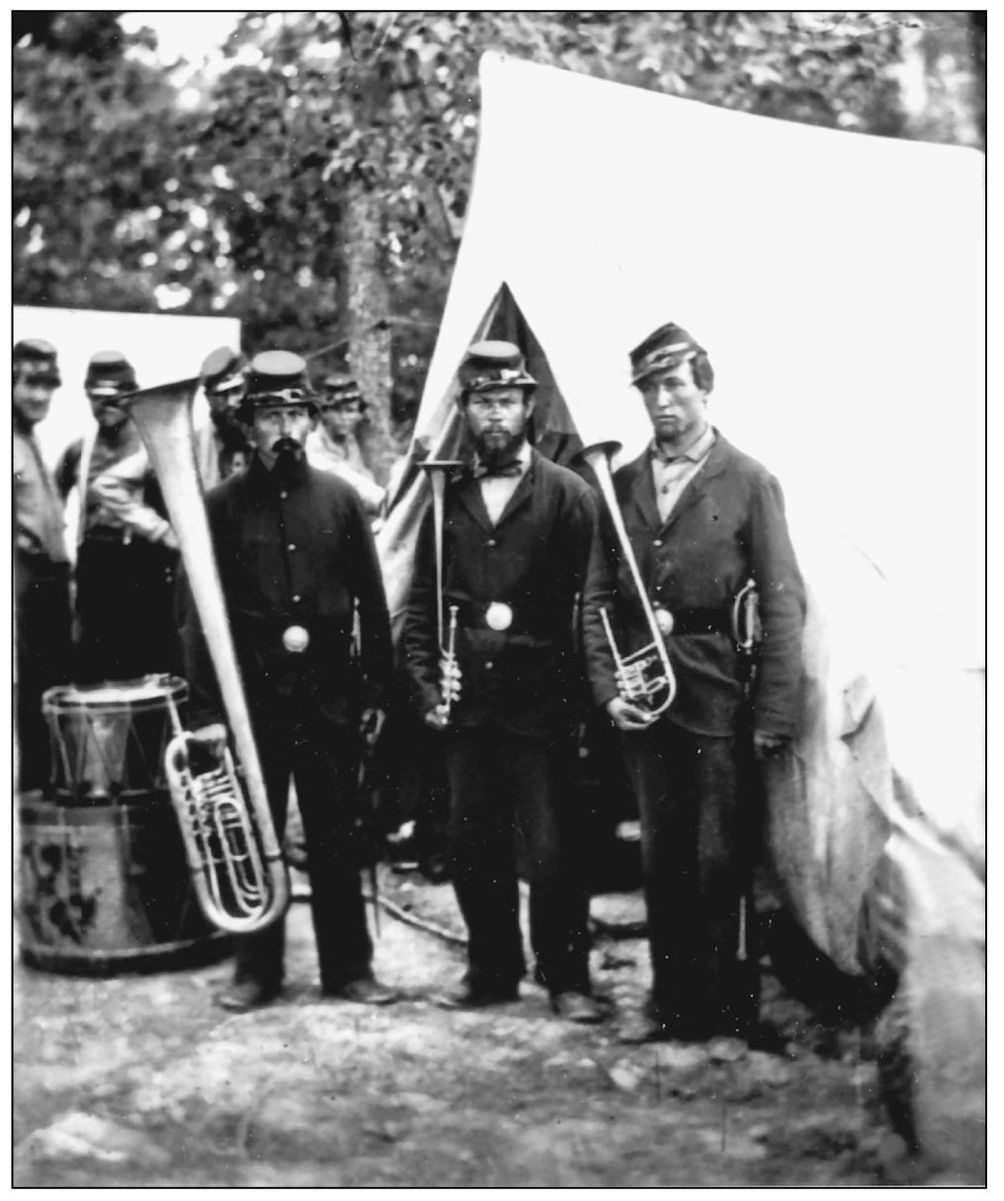

FINNEYS ORCHESTRA. After the death of John Bailey in 1871, Finney reorganized the music operation. Reintroduced as the Finney Orchestra, the organization experienced significant growth and gained a reputation of excellence throughout the region. With his acute eye for musical talent, Finney continued to enlist the finest musicians available, introducing the city to Harry P. Guy, Benjamin Shook, and the Stone brothersFred, William, and Charles. (Courtesy of the Nan Bostick collection.)