ISLAND of THE LOST

ISLAND of THE LOST

Also by Joan Druett

NONFICTION

In the Wake of Madness

Rough Medicine

She Captains

Hen Frigates

The Sailing Circle (with Mary Anne Wallace)

Captains Daughter, Coastermans Wife

She Was a Sister Sailor (editor)

Petticoat Whalers

Fulbright in New Zealand

Exotic Intruders

FICTION

Run Afoul

Shark Island

A Watery Grave

Abigail

A Promise of Gold

Murder at the Brian Boru

ISLAND of THE LOST

Shipwrecked at the Edge of the World

JOAN DRUETT

JOAN DRUETT

Published by

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, north Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

2007 by Joan Druett. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published simultaneously in Canada by Thomas Allen & Son Limited.

Design by Tracy Baldwin.

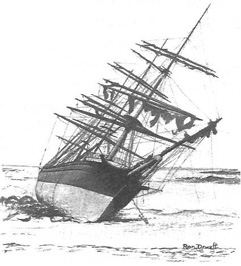

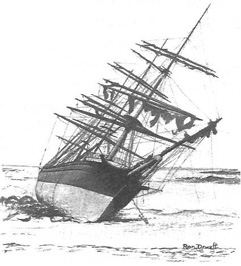

Illustration on page iii by Ron Druett.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Druett, Joan.

Island of the lost : shipwrecked at the edge of the world / by Joan Druett.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-1-56512-408-0 (hardcover)

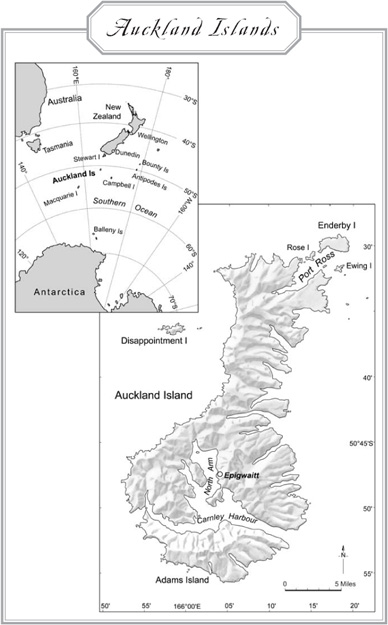

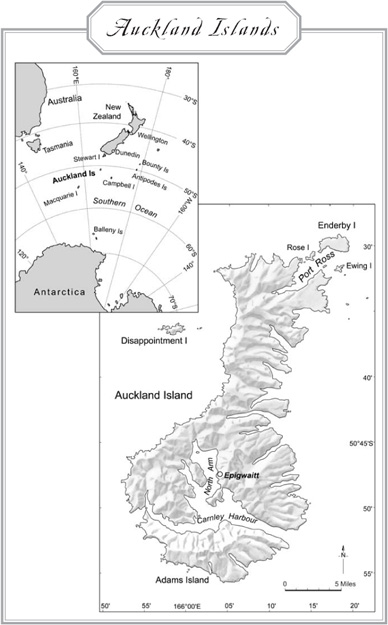

1. ShipwrecksNew ZealandAuckland Islands. 2. Grafton (Schooner).

3. Invercauld (Ship) 4. Survival after airplane accidents, shipwrecks, etc.New ZealandAuckland Islands. 5. Auckland Islands (N.Z.)Description and travel. I. Title.

G525.D78 2007

919.399dc22

2006031636

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

For Roberta McIntyre,

whose early encouragement

could not have been

more well timed.

It has seldom fallen to our lot as journalists to record a more remarkable instance of escape from the perils of shipwreck, and subsequent providential deliverance from the privations of a desolate island, after two years sojourn, than that we have now to furnish.

Southland News, July 29, 1865

The man who has experienced shipwreck shudders even at a calm sea.

Ovid

CONTENTS

ISLAND of THE LOST

ISLAND of THE LOST

ONE

A Sturdy Vessel

It was October 1863, early springtime in Sydney, Australia. The sun was bright, but a chilly wind whisked up the broad surface of the harbor, dashing reflections to pieces. Distant waves rushed against islands and rocky beaches, tossing up sprays of seabirds that cried out a raucous challenge as they circled the tall masts of ships. Wood-burning steam ferries chugged across the harbor from the terminus on Circular Quay, their whistles competing with the nearer rattle of the many horse-drawn trams in the city.

Close by, brigs, ketches, and schooners were tied up to quays, discharging sugarcane, coffee, tropical fruits, and coal, and loading ore and locally made machinery. Because of all this activity, the two men who searched the docks were forced to step around piles of sacks and stacks of barrels, and dodge stevedores who were bent low under heavy loads as they hurried in and out of the gaping doors of pitch-roofed warehouses. The cold wind whistled in the passages and alleys, bringing a smell of soot, dust, and eucalyptus trees, and the two men had their collars turned up, and their cold hands thrust deeply into their pockets. Still, however, they doggedly trudged from wharf to wharf, their eyes moving assessingly from one moored vessel to another.

Though as weatherbeaten as seamen, it was obvious that these two had come in from town. Both were well-groomed, handsome men, wearing city clothes; their good hats were set squarely on their heads, and their boots were decently shined. While they were about the same age, in their early thirties, the dark spade beard of the taller one was peppered with gray, in contrast to the slighter mans luxuriant moustache and whiskers, which were glossy brown beneath a strongly hooked nose. When they talked, it was evident that this latter fellow was French, because of his marked accent, while the taller mans voice held a burr that betrayed his northern England origins. However, they spoke seldom, because they had conferred already, and knew exactly what they wanted.

Everywhere there were notices nailed to walls, doors, bowsprits, and masts, announcing departures, advertising for men, or putting craft up for sale. It was these last that the men inspected, but so far without success, because it was so hard to find a vessel that met their specifications. They were hunting for a schooner that was small enough to be handled by four seamen, but strongly built as well. She had to be cheap, because they had not much funding for the ambitious venture they planned, but it was essential that she be sound. They intended to sail one thousand, five hundred miles sousoueast of Australia, as far as the Antarctic convergence, where immense billows rise up before the hurtling winds of latitude fifty, lifting taller than the highest mast before crashing down on ice-sheathed decks. Then they would turn their course to sail six hundred miles northeast and find an anchorage at tempest-swept Campbell Island. Naturally, then, they were most particular about the ship they had in mind.

All at once, the gray-bearded man spied a likely candidate. He stopped and pointed it out to the other, and then their steps quickened as they approached the vessel. Together, they eagerly read the notice tacked to the post where she was moored. Her name, they found, was Grafton. They stood back and studied her, assessing her lines and rigging, and watching the way her short, broad hull rocked heavily in the glossy harbor water. A two-masted craft, she was a topsail schooner, having one square sail set across the upper part of the foremast, and sails that ran fore and aft in the rest of the rigging. This helped make her easy for a small crew to handle, meeting the first of their specifications. What made her particularly attractive, however, were her sturdy build and her workmanlike, seaworthy air.

Again they studied the notice. According to the text, the Grafton had freighted coal from Newcastle, New South Wales, to Sydney, and was capable of carrying about seventy-five tons in her hold. It pleased them that she had been a coal carrier. In the tradition of Captain Cooks

Next page

ISLAND of THE LOST

ISLAND of THE LOST