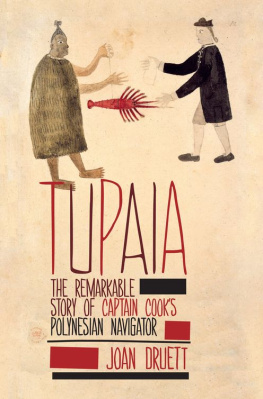

Tupaia

Captain Cooks Polynesian Navigator

Joan Druett

F OR BRIAN EASTON, in appreciation for his kindly hint that I should write Tupaias story, and his enthusiasm as he followed the progress of my researches

Contents

Introduction

1. In the beginning

2. The Dolphin

3. The Red Pennant

4. The Queen of Tahiti

5. The State Visit

6. Tupaias Pyramid

7. The Endeavour

8. Recognizing Tupaia

9. Tupaias Mythology

10. Return to Raiatea

11. Tupaias map

12. Latitude Forty South

13. Young Nicks Head

14. Becoming Legend

15. The Convoluted Coast of New Zealand

16. Botany Bay

17. The Great Barrier Reef

18. The Last Chapter

Commentary and Acknowledgements

Bibliography

TUPAIA

AN OLD SALT PRESS DIGITAL BOOK, published by Old Salt Press, a Limited Liability Company registered in New Jersey, U.S.A.

For more information about our titles, go to

www.oldsaltpress.com

2011 Joan Druett

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.

Cover photograph of investiture stone at Taputapuatea marae, Raiatea, courtesy Ron Druett

Cover sketch of H.M.S. Dolphin courtesy Ron Druett

Introduction

For more than two hundred years a painting of a Maori in a flax cloak and a European in gentlemans dress exchanging a lobster for a piece of cloth has been the subject of puzzled speculation. Carried to England in 1771 by Joseph Banks, who sailed as a scientific passenger on Captain James Cooks Endeavour , the work is now iconic. As a symbol of first contact between native and westerner, it is so evocative that it has been reproduced many times, though the identity of the artist remained unknown. Held by the British Museum and then the British Library after Bankss death, it was catalogued simply as the work of The Artist of the Chief Mourner, because of another strangely compelling watercolor by the same painter.

Then the mystery was solved. In 1998, Harold Carter, the biographer of Joseph Banks, described a letter he had found in the Banks collection, dated December 1812, which reads, in part:

... Tupia the Indian who came with me from Otaheite Learnd to draw in a way not Quite unintelligible The genius for Caricature which all wild people Posses Led him to Caricture me and he drew me with a nail in my hand delivering it to an Indian who sold me a Lobster but with my other hand I had a firm fist on the Lobster determind not to Quit the nail till I had Livery and Seizin of the article purchasd...

The lapse of forty-three years had misled Banks into remembering that the piece of cloth he had offered for the lobster had been a nail. Despite this, it was now clear that The Artist of the Chief Mourner was the extraordinary Polynesian who sailed with Captain Cook from Tahiti, and acted as the Europeans go-between in dangerous first contacts with the Maori people.

His name was Tupaia.

Joseph Banks bartering with a Maori for a crayfish.

Watercolor by Tupaia. (Courtesy of the British Library, 15508/12)

T UPAIA, A GIFTED LINGUIST and a devious politician, could aptly be called the Machiavelli of eighteenth century Tahiti. In June 1767, when the first European ship, H.M.S. Dolphin, arrived at the island, Tupaia became Tahitis foremost diplomat. He took on the same role soon after the Endeavour dropped anchor in Tahiti in April 1769, and then, when the ship departed, Tupaia sailed with them.

He was not afraidPolynesians were never afraid to voyage. Over the next two centuries thousands of fellow Polynesians would sign onto European ships with the same confidence and courage, to work side-by-side with British sailors and American whalemen. Tupaia was special, though, because in his own culture he was a master navigator, highly skilled in astronomy and navigation, and an expert in the geography of the Pacific. In normal times he would have kept his privileged knowledge a deadly secret, never revealed to anyone outside his select group. But, as an exile... and a man who had narrowly avoided capture and sacrifice by his enemies... he was willing to share this sacred lore.

Yet Tupaia, for all his generosity and brilliance, has never been part of the popular Captain Cook legend. This is largely because he died of complications from scurvy seven months before the ship arrived home. Once he was gone, his accomplishments were easily forgottenindeed, by removing Tupaia from the story, what the Europeans had achieved seemed all the greater. James Cook could have resented the fact that Tupaia had been hailed by the Maori as the admiral of the expedition. Seemingly, too, the sacred gifts that Tupaia had received from New Zealand chiefs had proved useful for presentation to monarchs and museums. It was also important that Tupaia should be forgotten when James Cook received his medal from the Royal Societyfor the remarkable feat of never losing a man from scurvy!

Partly because of all this, the biography of the unacknowledged Tahitian who contributed so much to the success of the Endeavour voyage has never been written. Polynesia relied on oral histories, and so what we know about the eighteenth century Pacific comes from the diaries, journals, logbooks, and memoirs of European witnesses, and the record has been too one-sided for a rounded account. Lately, however, folklorists and anthropologists, by paying attention to Polynesian myths and memories, have added immensely to our understanding. By consulting this new, rich literature, as well as the journals and memoirs written by the men who dealt with Tupaia on land and sailed with him at sea, the story of this extraordinary genius can at last be told.

Next page