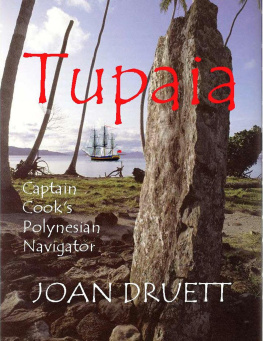

In appreciation of his kindly hint that I should write Tupaias story, and his enthusiasm as he followed the progress of my researches.

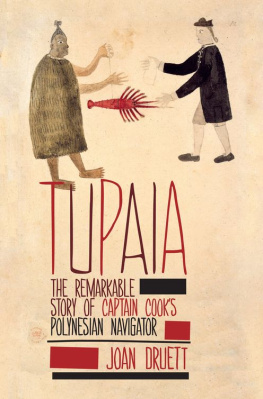

For more than two hundred years a painting of a Maori in a flax cloak and a European in gentlemans dress exchanging a lobster for a piece of cloth has been the subject of puzzled speculation. Carried to England in 1771 by Joseph Banks, who sailed as a scientific passenger on Captain James Cooks Endeavour, the work is now iconic. As a symbol of first contact between native and westerner, it is so evocative that it has been reproduced many times over the years, though the identity of the artist remained unknown. Held by the British Museum and then the British Library after Bankss death, it was catalogued simply as the work of The Artist of the Chief Mourner, because of another strangely compelling watercolour by the same painter.

THEN THE MYSTERY WAS solved. In 1998, Harold Carter, the biographer of Joseph Banks, described a letter he had found in the Banks collection, dated December 1812, which reads in part:

Tupia the Indian who came with me from Otaheite Learnd to draw in a way not Quite unintelligible The genius for Caricature which all wild people Posses Led him to Caricature me and he drew me with a nail in my hand delivering it to an Indian who sold me a Lobster but with my other hand I had a firm fist on the Lobster determind not to Quit the nail till I had Livery and Seizin of the article purchasd

THE LAPSE OF FORTY-THREE years had misled Banks into remembering that the piece of cloth he had offered for the lobster had been a nail. Despite this, it was now clear that The Artist of the Chief Mourner was the extraordinary Polynesian who sailed with Captain Cook from Tahiti, and acted as the Europeans go-between in dangerous first contacts with the Maori people.

His name was Tupaia.

Tupaia, a gifted linguist and a devious politician, could aptly be called the Machiavelli of eighteenth-century Tahiti. In June 1767, when the first European ship, HMS Dolphin, arrived at the island, Tupaia became Tahitis foremost diplomat. He took on the same role soon after the Endeavour dropped anchor in Tahiti in April 1769, and then, when the ship departed, Tupaia sailed with it.

He was not afraid Polynesians were never afraid to voyage. Over the next two centuries thousands more Polynesians would sign on to European ships with the same confidence and courage, to work side by side with British sailors and American whalemen. Tupaia was special, though, because in his own culture he was a master navigator, highly skilled in astronomy and navigation, and an expert in the geography of the Pacific. In normal times he would have kept his privileged knowledge a deadly secret, never revealed to anyone outside his select group. But, as an exile and a man who had narrowly avoided capture and sacrifice by his enemies he was willing to share this sacred lore.

Yet Tupaia, for all his generosity and brilliance, has never been part of the popular Captain Cook legend. This is largely because he died of complications from scurvy seven months before the ship arrived home. Once he was gone, his accomplishments were easily forgotten indeed, by removing Tupaia from the story, what the Europeans had achieved seemed all the greater. James Cook could have resented the fact that Tupaia had been hailed by the Maori as the admiral of the expedition. Seemingly, too, the sacred gifts that Tupaia had received from New Zealand chiefs had proved useful for presentation to monarchs and museums. It was also important that Tupaia should be forgotten when James Cook received his medal from the Royal Society for the remarkable feat of never losing a man to scurvy!

Partly because of all this, the biography of the unacknowledged Tahitian who contributed so much to the success of the Endeavour voyage has never been written. Polynesia relied on oral histories, and so what we know about the eighteenth-century Pacific comes from the diaries, journals, logbooks and memoirs of European witnesses, and the record has been too one-sided for a rounded account. Lately, however, folklorists and anthropologists, by paying attention to Polynesian myths and memories, have added immensely to our understanding. By consulting this new, rich literature, as well as the journals and memoirs written by the men who dealt with Tupaia on land and sailed with him at sea, the story of this extraordinary genius can at last be told.

At the instant of his birth, Tupaias life hung in the balance. Infanticide was widely practised on his native island, Raiatea, partly because of overcrowding, and partly because of social pressure. The father might not want to acknowledge the child. The moment a chiefs heir was born, he ruled as his sons regent, and was no longer an arii in his own right, and so he might order the child to be smothered.

ONCE TUPAIA LET OUT his first cry, however, he was safe. Indeed, he was looked after very well. Our greater understanding of Polynesian society, combined with details such as the style of tattooing on Tupaias body, which tells us much about the class to which he belonged, means we can clearly imagine what his early life was like. A new baby was considered highly sacred, and for a while Tupaia could not be held by anyone except his mother. After cleansing herself in a sweat bath, followed by a dip in a stream, she showed the infant to his father, who recognised him as his son by making an offering at the marae, where a priest buried the umbilical cord with appropriate prayers. Then Tupaias mother secluded herself, as she had been infected by his sanctity. Anything he touched became equally dangerous. Shrubs he brushed against had to be cut down.

These hampering prohibitions were gradually removed by profaning the baby, or making him noa ordinary in a series of rites called amoa. As the months went by, his father was able to hold him, and after another interval Tupaia was introduced to his uncles, then the rest of his extended family. Finally, he was tattooed with a special mark on the inside of each elbow, and proclaimed an ordinary human being, free to play and experiment with the world.

This world included the sea. Tupaia was able to swim before he could walk. By the age of five he was listening to stories of epic voyages that did more than entertain, introducing him to the mysteries of navigation. Within a year he was being taken along on voyages, to learn that the ocean was not just a great, formless expanse of water with the occasional reef or island passing by, but a web of distinct and well-travelled seaways. Soon, he would know what distance to expect to cover on an average days sail on each route, and could recognise the dusk-time shore-seeking flights of different kinds of seabirds. As the months went by, he learned the patterns of currents and swells, and absorbed an impressive knowledge of star bearings. Great directional stars and constellations Matarii (the Pleiades), Ana muri (Aldebaran), Ana mua (Antares) and Te matau o Maui (the hook of Scorpio) became as familiar to him as friends. He was an expert fisherman, too, able to forecast changes of wind and weather, and their effect on schooling and spawning.

At home, young Tupaia surfed with his playmates, wrestled, practised the noble sport of archery, and fought mock battles with a club like a quarterstaff. At the same time he learned traditional crafts by watching and assisting carpenters, canoe-builders and priests, as he grew older. A small number of outstanding boys, who had to be intelligent, tall, flawless in looks, deft and sure-footed, as well as high-born, were chosen to go to schools fare airaa upu