Published in 1993

Academy Chicago Publishers

213 West Institute Place

Chicago, Illinois 60610-3125

Printed and bound in the USA

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Cook, James, 1728-1779.

Voyages of discovery / Captain Cook.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-89733-316-0 (pbk.)

1. Cook, James, 1728-1779. 2. Voyages around the world.

3. ExplorersGreat BritainBiography. I. Title.

G420.C62c66 1991

910.924-dcl9

88-24132

CIP

Cover design and art by Matthew Nutting

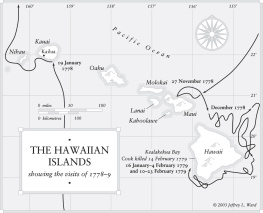

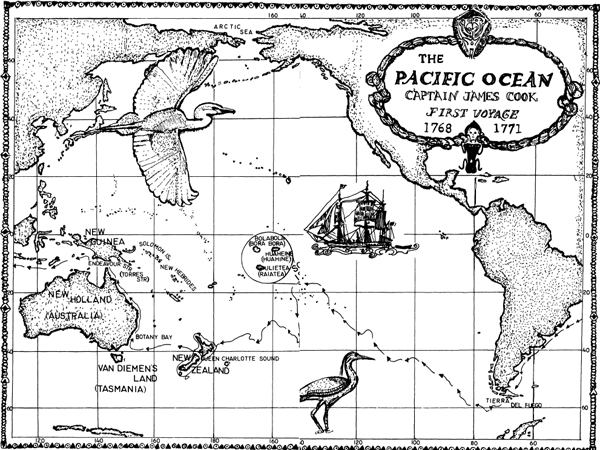

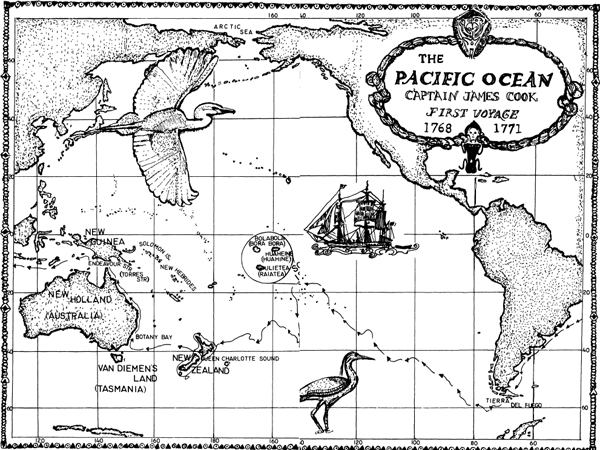

Maps by Julia Anderson-Miller

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Few explorers have captured the imagination of the public as has James Cook. When he set off on his first circumnavigation in 1768, he was a relatively obscure naval lieutenant. But his reputation rose steadily with each voyage, largely because the English and other Europeans were fascinated with the romance of discovery as well as with the reports of sexual license encountered by his crew in Tahiti and other Polynesian islands. Cooks death in 1779 at the hands of Hawaiians added to his mystique. Accounts of his three voyages, whether authorized or anonymous, became the most popular travel literature of the period and remained so well into the 19th century. Within a decade of his death, more than 40 editions of Cooks voyages had been published, including editions in German, French, Dutch, Italian, and Russian.

Cook, born the son of a farm laborer in 1728, began his career as a bound apprentice on a collier where, for several years, he learned basic seamanship and navigation. In 1755 at the onset of what Americans call the French and Indian War, he enlisted in the Royal Navy as an able seaman on board the Eagle, a 60-gun ship under the command of Captain Hugh Palliser, who became Cooks patron.

During most of the war, Cook was stationed in North America, where he surveyed and charted the St. Lawrence River in preparation for the capture of Quebec. He took part in Wolfes landing at Quebec, being in charge of some of the boats used to seize the city, and ultimately Canada, from the French.

With the French expelled from North America, the Admiralty wanted to consolidate its knowledge of the American coast In 1763, Cook was sent out in his first command to survey the little-known coasts of Newfoundland, where Palliser was then governor. Cooks published charts of Newfoundland and Labrador were remarkably accurate and were not superseded for a century. By chance, he observed a total eclipse of the sun in 1766 and communicated his results to the Royal Society. Thus Cooks abilities became recognized by both the Admiralty and the Royal Society soon after the war.

The 1760s saw two occurrences of a rare astronomical event: the transit of the planet Venus across the face of the sun. Transits of Venus have been observed only five times in history, never in the 20th century. The significance of the event lay not in its rarity (the next transits would not occur for more than a century, in 1874 and 1882). Rather, in 1716 Edmund Halley had suggested a method for calculating the earths mean distance from the sun by timing the passage of Venus across the solar disk from disparate locations. In the 1761 transit, European scientific societies had stationed more than 100 observers in various places. Their results had been disappointing, largely because their observing stations were too close together. The astronomers primary concern was to station observers as far from Europe as possible at the next transit of Venus (3 June, 1769), preferably in the southern hemisphere where the transit would be most visible. South seas were suggested, but not a single island was known to lie within the part of the South Pacific where the transit would be visible.

Astronomys importance for navigation as a means of calculating latitude and longitude was well understood by King George III, his ministers, and the Admiralty. The British government also recognized the importance of scientific achievements to national pride, particularly since in 1761 France had sent out twice as many observers as had England. So in 1768 when the Royal Society petitioned the King to provide a ship and crew to take two astronomers to the South Pacific, the government was inclined to be sympathetic. But other concerns also weighed in favor of such an expedition.

France was interested in opening up a new colonial empire to replace its Canadian colonies, lost in the recent war, while the English were determined to prevent French expansion and to extend their own political influence into the south seas. English expansion into the Pacific would improve trade routes to Asia and might add colonies and natural resources to the empire.

Central to these political and economic aspirations was the long-cherished idea that a vast, undiscovered continent existed in the South Pacific: the so-called Terra Australis Incognita. Geographers had argued that such a continent must lie in the south seas to balance Eurasia in the northern hemisphere. Alexander Dalrymple, the leading proponent of this theory in England, calculated that Terra Australis must extend 5,323 miles from the west coast of New Zealand to Staten Land near the southern tip of South America. He suggested that this undiscovered continent might have a population of 50 million.

About the same time, renewed interest in another Pacific question was growing in England: was there a Northwest Passage that linked the Atlantic to Asia through Arctic seas? Such a passage would promote trade by reducing travel time between England, North America, and Asia.

Soon after the war with France, the Admiralty took up the quest for a Northwest Passage, in 1764 commissioning Commodore John Byron to the Pacific in the Dolphin. On this short, two-year circumnavigation Byron succeeded in discovering only a few Polynesian islands. Three months after the Dolphins return, the Admiralty sent Samuel Wallis (who had accompanied Byron) back out to the Pacific in the Dolphin to find the great southern continent. He was accompanied by Philip Carteret in the Swallow. The two ships suffered in the Straits of Magellan and became separated. Although both commanders discovered islands in Polynesia and Carteret later made numerous discoveries around New Guinea, neither found Terra Australis. When Wallis returned to England in May 1768, his voyage had been unsuccessful, with one exception: he found, as he had been instructed to do, a place of consequence in the South Pacific, the island of Tahiti.

Just before Wallis returned to England, the Admiralty acceded to the Royal Societys request for a South Seas voyage to observe the transit of Venus. But the Admiralty bluntly rejected the Societys request that Dalrymple receive a captains commission as leader of the expedition, on the grounds that Dalrymple was not a Kings officer. Dalrymple, being as obstinate as he was opinionated, refused to go in any other capacity. In the end, the Royal Society suggested James Cook, an obscure but capable naval officer distinguished for his surveys and astronomical observations. Charles Green, then assistant at the Royal Observatory, was selected to accompany him. This choice suited the Admiralty, and Cookreceived his commission and promotion to lieutenant a few days after Walliss arrival.

While Cook readied his newly christened

Next page