Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Founded in 1846, the Hakluyt Society seeks to advance knowledge and education by the publication of scholarly editions of primary records of voyages, travels and other geographical material. In partnership with Routledge and using print-on-demand and e-book technology, the Society has made re-available all 290 volumes comprised in Series I and Series II of its publications in both print and digital editions. For information about the Hakluyt Society visit www.hakluyt.com.

ISBN 9781472453259 (hbk)

THE JOURNALS OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK ON HIS VOYAGES OF DISCOVERY

EDITED FROM THE ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPTS BY

J. C. BEAGLEHOLE

FOUR VOLUMES AND A PORTFOLIO

III

THE VOYAGE OF THE

RESOLUTION AND DISCOVERY

1776-1780

PART ONE

HAKLUYT SOCIETY

EXTRA SERIES No. XXXVI

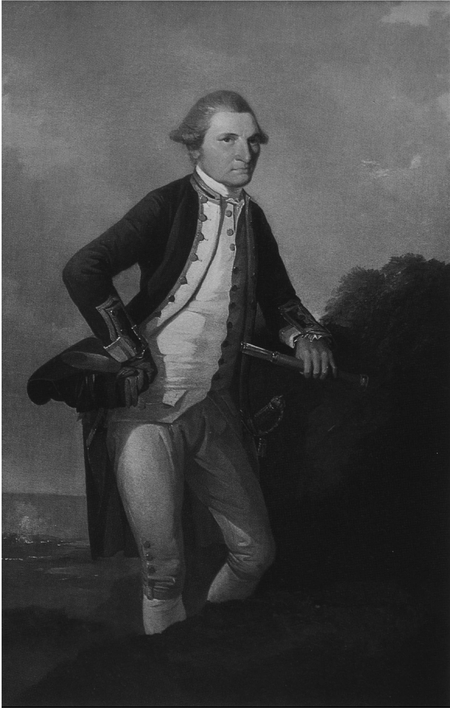

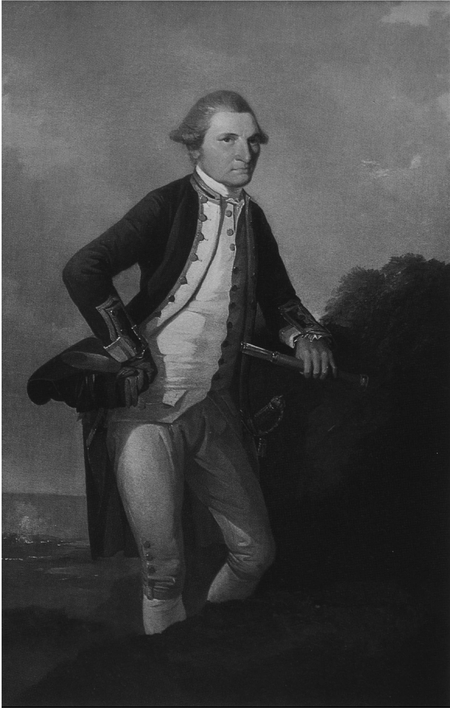

Portrait of Captain Cook

By John Webber

THE JOURNALS OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK ON HIS VOYAGES OF DISCOVERY

*

THE VOYAGE OF THE RESOLUTION AND DISCOVERY 1776-1780

EDITED BY

J. C. BEAGLEHOLE

PART ONE

CAMBRIDGE

Published for the Hakluyt Society

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

1967

N o one can study attentively the records of Cook's third, and last, voyage without being convinced that it was of the same order of greatness as its two predecessors. It differs from them in scope, geographically speaking: its principal new discoveries were North Pacific, not South Pacific, ones. It lasted a year longer than either of them. In the main stated object of the instructions to its commanderthe discovery of the North-West Passageit failed utterly, though the title-page of the official publication describing it put an elaborate gloss on that failure with its references to the coast and the extent of North America. Yet its discoveries were remarkable, and one cannot think the gloss unjustified. There are also in it what one must call elements of drama -though the great drama is, of course, the death of Cook. Cook dies, and the voyage goes on; but without the central figure it by no means loses its interest. It is, indeed, still his voyage.

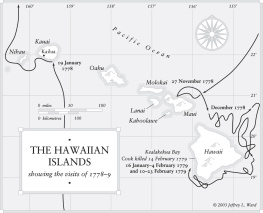

Cook's death brings his journals to an end. The voyage is still his. What, then, are we to do to complete its documentation? We may note, too, that his own documentation, through some unhappy fate that afflicted his papers, ceases a month before his death. There is no single journal that adequately covers the remainder of the voyage. Cook was succeeded by Gierke, who could write but was a dying man, and died six months after Cook. Gierke was succeeded by Gore, who could not write. The Admiralty got over the difficulty, in its official publication, by putting Lieutenant King, a highly literate person, to complete the account in a whole third volume. We cannot make King complete our account, in an edition devoted to the original manuscripts; for King's own journal breaks down. At the same time we have a wealth of material, however uneven. The 'journal' here presented, therefore, after Cook's death, is a composite one, and it contains, for what seems sufficient reason, some repetition. This repetition comes mainly in the Hawaiian period, in printing as part of the main text, alternately, both Gierke and King Clerke because of his key position as commander and his idiosyncrasy of expression; King because he was a chief actor as well as a careful observer and a conscientious recorder. While Clerke can still write, he is the best man for the weeks of navigation, on the passage to Kamchatka and in the Arctic episode that follows. For what happens ashore on the first visit to Kamchatka, however, one must revert to King; after Gierke gives up, among the ice, to Burney; on the second visit to Kamchatka, to the skeleton entries of Edgar, the Discovery's master; on the passage home, to the brief pages, not strictly a journal at all, though the only connected account we have, of the midshipman George Gilbert. The concatenation is not completely satisfactory: at least we get the voyage as seen from both the Resolution and the Discovery.

In this volume a great deal of space, it will be observed, is occupied in the appendixes by extracts from journals other than Cook'sso much so that the binding of the volume in two separate parts is necessitated. The number of extant logs and journals for the voyage is only half a dozen greater than for the second voyage, and there is the normal proportion of negligible ones. On the other hand, there are more persons who realize the importance of the voyage, more who write at length, who have something individual to contribute to its history, whose contribution cannot simply be incorporated in a footnote or a series of footnotes. One must, for example, have large extracts from the invaluable Clerke and King; though such is the quantity of writing that one can afford to dispense in the end with anything extended even from so good a writer as Burney. There seems no alternative to providing two of the journals in full, whatever the space they occupythose of Anderson and Samwell. For the account of the first voyage Hawkesworth drew heavily on Banks; Cook himself drew much on Wales for his own account of the second; for the third he was prepared to draw similarly on Anderson, and Dr Douglas, preparing Cook for the press, did use a vast amount of Anderson. Anderson cannot go into footnotes, except once or twice when a sort of immediate 'confrontation' with Cook seems called for; it is all or nothing. Similarly with Samwell, known heretofore mainly as the author of a pamphlet on Cook's death; and if one does print him all, it is better as part of this work, where the cross-lights are closer, than separately. Apart from this sheer bulk, the plan of the appendixes differs in only one way from that previously adopted, in the omission of a section devoted to Cook's own letters and reports during the voyage. They are too few in number, and those few can more conveniently be incorporated in the general Calendar of Documents.

There are passages of more massive annotation in this volume than in the two previous ones. The main divisions of the voyage are clear enough; some of its details have been far from clear. Much work had If one adopts again the primary object of deciding precisely where Cook went, where he was at any given moment, why he said what he did by way of description and explanation, then one has a wearing task indeed; but it must be undertaken. I have had to undertake it, except in one particular spot, with the help only of charts and the printed word against which to check the charts and the written words produced on the voyage; and no one knows better than I how many conjectures I have had to make, and how fruitful how destructive, sometimes, to laborious reconstructionmight be a detailed examination from the sea of that long coast, with the modern chart and modern instruments of navigation at one's hand as well as Cook's journal under one's eye. I am well aware of the Johnsonian dictum that no man is talked down but by himself; nevertheless I feel it due to the reader to make clear that I enter all my statements, however dogmatic they may appear, with due reserve and modesty. How could one read Vancouverwhom I have quoted so much and not be aware of the hazards of observation from a distance, even under favourable conditions? For cold fact one can lean on the South-East Alaska Pilot, the Bering Sea and Strait Pilot ; but they do not explain the accidents of weather, on some particular day in 1778, which made Cook write as he did.