THE WAR-BOATS OF THE ISLAND OF OTAHEITE [TAHITI], William Hodgess largest painting (nearly 2m x 3m) recollecting Cooks second Pacific voyage. It shows Tahitian preparations in an ongoing local war with the people of the neighbouring island of Moorea. It was completed and shown at the Royal Academy in 1777.

AUTHORS NOTE

This book is a general introduction to European voyages in the Pacific from the 1760s to the 1830s. With some revisions, it combines chapters from two books previously published by the National Maritime Museum in 2002 and 2005. The original focus was on the principal British expeditions up to 1803, starting with those of Captain Cook, and the two European ones French and Spanish most immediately prompted by them. Here the coverage has been extended to include a new final chapter on the Beagle surveys of 182636 and additional sections on the artists who accompanied and illustrated the British voyages.

Nigel Rigby is former Head of Research at the National Maritime Museum, which he first joined in 1996. Pieter van der Merwe was on its full-time staff in various roles from 1974 to 2015, latterly as its General Editor for over 20 years. Glyn Williams is Emeritus Professor of History, Queen Mary University of London. His co-authors are especially grateful that, in his 86th year, he has been able and willing to assist with this combined new edition. He is the author of the Introduction and and the artist entries.

C ONTENTS

F OREWORD

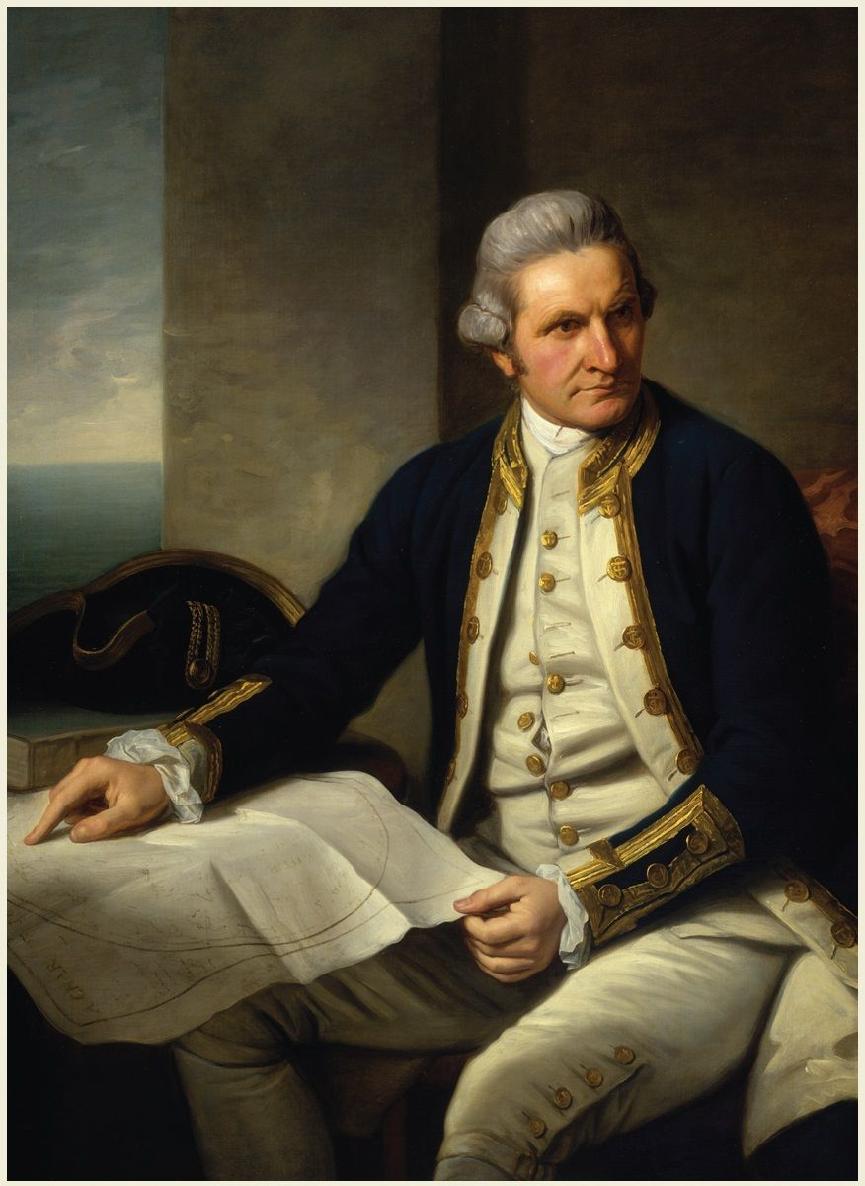

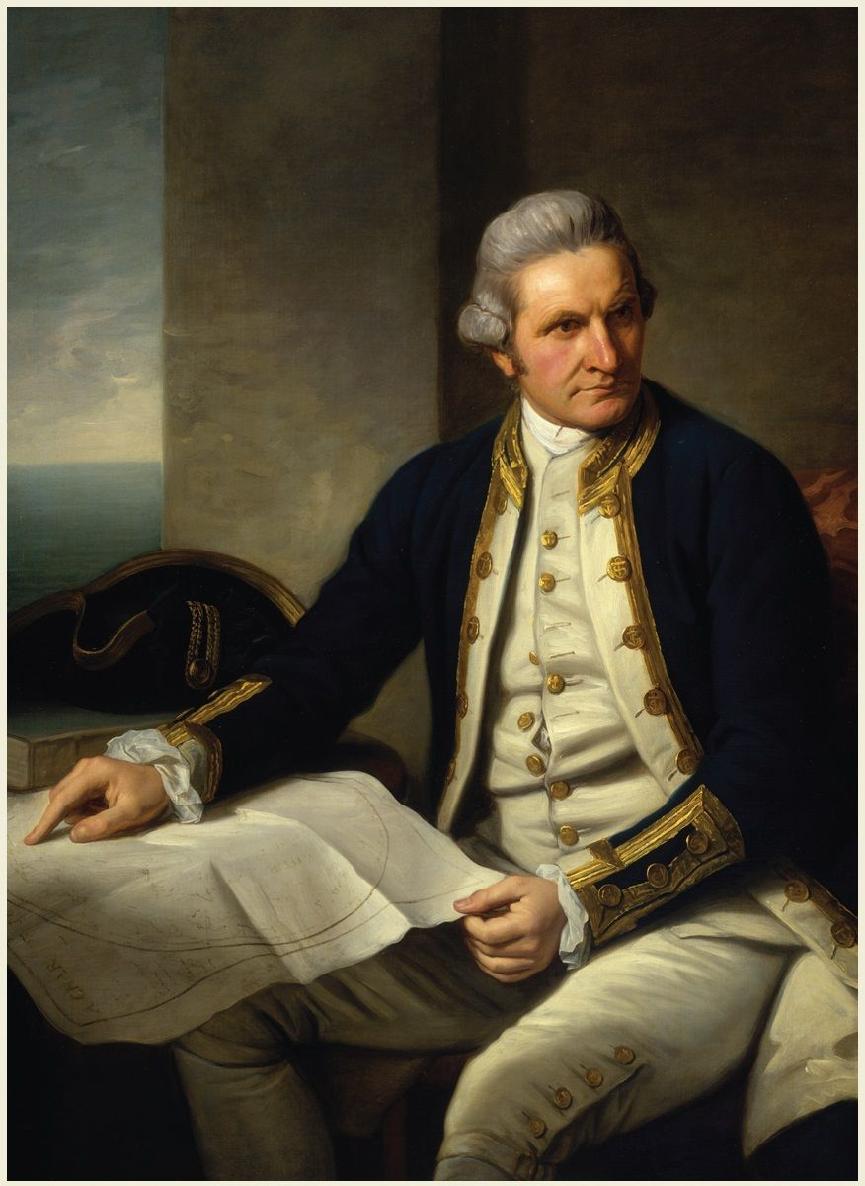

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK; oil painting by Nathaniel Dance.

Anniversaries present opportunities for both museums and publishers. The former can seize the occasion to reinterpret historical events in special exhibitions and new galleries; the latter can do so more widely including through museum bookshops both to new generations of readers and to older ones enjoying aspects of a notable story again.

In 1768, after the ships refitting for exploration at the Royal Dockyard, Deptford (a mere kilometre upriver from the site of the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich), Lieutenant James Cook set sail in the Endeavour on the first of his three great Pacific expeditions, which makes 2018 its 250th anniversary. This occasion also coincides with the opening of our new gallery about voyages to the Pacific in the late eighteenth century, which includes highlights from the Museums large and rich collections on Cook and those who followed in his wake.

The story here covers even wider ground, from early European exploration of the great South Sea in the 1500s to the 1830s voyage that led to Charles Darwins theory of the origin of species. All three authors are masters in various aspects of this enormous subject, and are able to link and clarify its complex parts in an engaging as well as informative way. We are particularly grateful to Glyn Williams, for whom Pacific history has been a lifetime study. It is also a pleasure to thank Nigel Rigby and Pieter van der Merwe, not least since this is their last publication as staff members at Greenwich, after a combined service of over 60 years.

Dr Kevin Fewster, AM

DIRECTOR, ROYAL MUSEUMS GREENWICH

I NTRODUCTION

R ESOLUTION AND DISCOVERY REFITTING IN SHIP COVE, NOOTKA SOUND (detail); pen, ink and watercolour by John Webber, 1778.

On their arrival off the west coast of North America during Cooks last voyage, his ships were in a poor condition and badly needed a refit. Webbers informative panoramic drawing shows Discoverys foremast being replaced. The expeditions astronomical observatory tents have been set up on a rocky point at the centre, and energetic contact and trade with local people are evident in the number of canoes present.

EL MAR DEL SUR

By the early sixteenth century the successors of Columbus were becoming aware that beyond the newly discovered Americas stretched an unknown ocean, possibly of great size. Its waters were first sighted by Europeans in 1513 when the Spanish conquistador Vasco Nez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama from the Caribbean to the shores of el Mar del Sur, or the South Sea (so called to distinguish it from the Spaniards Mar del Norte, or Atlantic). In a moment of high drama, Balboa, in full armour, strode in knee-deep to claim it for Spain, but the newcomers took many years to realise the vast extent of its waters and lands. The single most important advance in their knowledge came only a few years after Balboas sighting.

In 1519 Ferdinand Magellan left Spain with five ships to search for a route from the South Atlantic into the new ocean and thence westward to the Moluccas (the Spice Islands), which were at this time being reached by Portuguese traders from the Indian Ocean. If the Spaniards were to find such a route it would demolish the hypothesis of Ptolemy, the Alexandrian scholar who in the second century AD had visualised the seas of the southern hemisphere as enclosed by a huge southern continent that was joined to both Africa and Asia. The Portuguese navigators who rounded the Cape of Good Hope had shown that there was open water between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and Magellan in turn found a route near the tip of South America in the form of the tortuous 350-mile strait that was soon to bear his name. Battling against squalls, desertions and shipwreck, he took 37 days to get through it and reach the ocean which he (or his chronicler, Pigafetta) named the Pacific. As later storm-tossed mariners were to point out, it was not always the most appropriate of names. Picking up the South-East Trades, Magellans two remaining vessels followed a diagonal route north-west across the ocean. For 15 weeks they sailed on, sighting only two small, uninhabited islands. Men died of scurvy and starvation as the crews were reduced to eating the leather sheathing of the rigging until, in March 1521, the ships reached the island of Guam in the North Pacific, and from there sailed to the Philippines and the Moluccas. Magellan died in the Philippines and only his ship, Vittoria, now commanded by Juan Sebastin de Elcano, returned to Spain in 1522 to complete the first circumnavigation of the globe. No other single voyage has ever added so much to the dimension of the world, Oskar Spate has written, and dimension is the key word. For the tracks of his ships had shown the daunting and apparently empty immensity of the Pacific, where a voyage of almost four months continuous sailing had encountered no more than two specks of land.

An ocean traversed only across unprecedentedly unimpeded distances had been revealed; but to talk of its being unknown, then discovered and explored by Europeans which this book necessarily does hides the fact that long before Magellan it had already experienced a complex process of exploration, migration and settlement. The chart drawn for James Cook in 1769 by Tupaia, a priest, or arii, from the Society Islands, gives some indication of the range of geographical information held, almost solely in memory, by Pacific peoples before Europeans arrived. Centred on Tahiti, it marked 74 islands, scattered over an area of ocean 3,000 miles across and 1,000 miles from north to south. The type of craft used in Pacific voyaging ranged from the small single-hulled outriggers of Micronesia to giant double-hulled ones in Polynesia, some of which were longer than European discovery vessels and could make voyages of several thousand miles. Navigation was by observation of stars, currents, wave and wind patterns, and by the shape and loom of the land, rather than by instrument. Long-distance voyages were made that led to the occupation by Polynesians of lands as far distant from one another as the Hawaiian Islands and New Zealand. Europeans were slow to appreciate the navigational skills of the Pacifics inhabitants, and today there is still uncertainty about how many great voyages of the pre-European period were planned rather than fortuitously accidental, or a mix of the two.

Next page