Laurence Bergreen - Magellan: Over the Edge of the World

Here you can read online Laurence Bergreen - Magellan: Over the Edge of the World full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Roaring Brook Press, genre: Adventure. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Magellan: Over the Edge of the World

- Author:

- Publisher:Roaring Brook Press

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Magellan: Over the Edge of the World: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Magellan: Over the Edge of the World" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Magellan: Over the Edge of the World — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Magellan: Over the Edge of the World" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Zata Brielle Fray

Juan de Aranda (merchant)

Beatriz Barbosa (Magellans wife)

Diogo Barbosa (Magellans father-in-law)

Charles I (king of Spain)

Ruy Faleiro (cosmographer)

Manuel I (king of Portugal)

Juan Rodrguez de Fonseca (bishop of Burgos, later archbishop)

THE ARMADA DE MOLUCCA

(listed according to positions at the outset of the circumnavigation)

Trinidad

FERDINAND MAGELLAN (captain general)

Francisco Albo (pilot)

Duarte Barbosa (Magellans brother-in-law)

Enrique (Magellans slave, also an interpreter)

Gonzalo Gmez de Espinosa ( alguacil , or master-at-arms)

Estvo Gomes (pilot)

Gins de Mafra (pilot)

Martn Mndez (purser)

lvaro de Mesquita (Magellans cousin)

Antonio Pigafetta (chronicler)

Cristvo Reblo (Magellans illegitimate son)

Pedro de Valderrama (chaplain)

San Antonio

JUAN DE CARTAGENA (captain and inspector general)

Antonio de Coca (fleet accountant)

Gernimo Guerra (clerk)

Diego Hernndez (mate)

Juan de Lorriage (master)

Pero Snchez de la Reina (priest)

Andrs de San Martn (cosmographer and astronomer)

Concepcin

GASPAR DE QUESADA (captain)

Hernando de Bustamante (barber)

Joo Lopes Carvalho (pilot)

Joozito Carvalho (cabin boy)

Juan Sebastin Elcano (master)

Luis de Molino (servant)

Victoria

LUIS DE MENDOZA (captain)

Santiago

JUAN RODR GUEZ SERRANO (captain)

Dates are given in the Julian calendar, in use in Europe at the time of Magellans voyage. In 1582, sixty years after the completion of Magellans voyage, Spain, France, and other European countries migrated to the Gregorian calendar, decreed by Pope Gregory XIII and designed to correct flaws in the Julian system. Ten days were omitted, so that October 5, 1582, in the Julian calendar suddenly became October 15, 1582, in the Gregorian.

Magellans voyage had its own record-keeping issues. The dates of various events recorded by the two chief chroniclers of the expedition, Antonio Pigafetta and Francisco Albo, occasionally diverge by one day. Albo, a pilot, followed the custom of ships logs, which began the day at noon rather than at midnight. In contrast, Pigafetta used a non-nautical frame of reference in his diary. So an event occurring on a given morning might have been put down a day apart in the records maintained by the two.

Finally, the international date line, demarcating one calendar day from the next, did not exist at the time of Magellans voyage. (It now extends from the North Pole to the South Pole, through the Pacific Ocean.) As Albo and Pigafetta neared the completion of their circumnavigation, they were astonished to note that their calculations were off and that their voyage around the world had taken one day longer than they had thought.

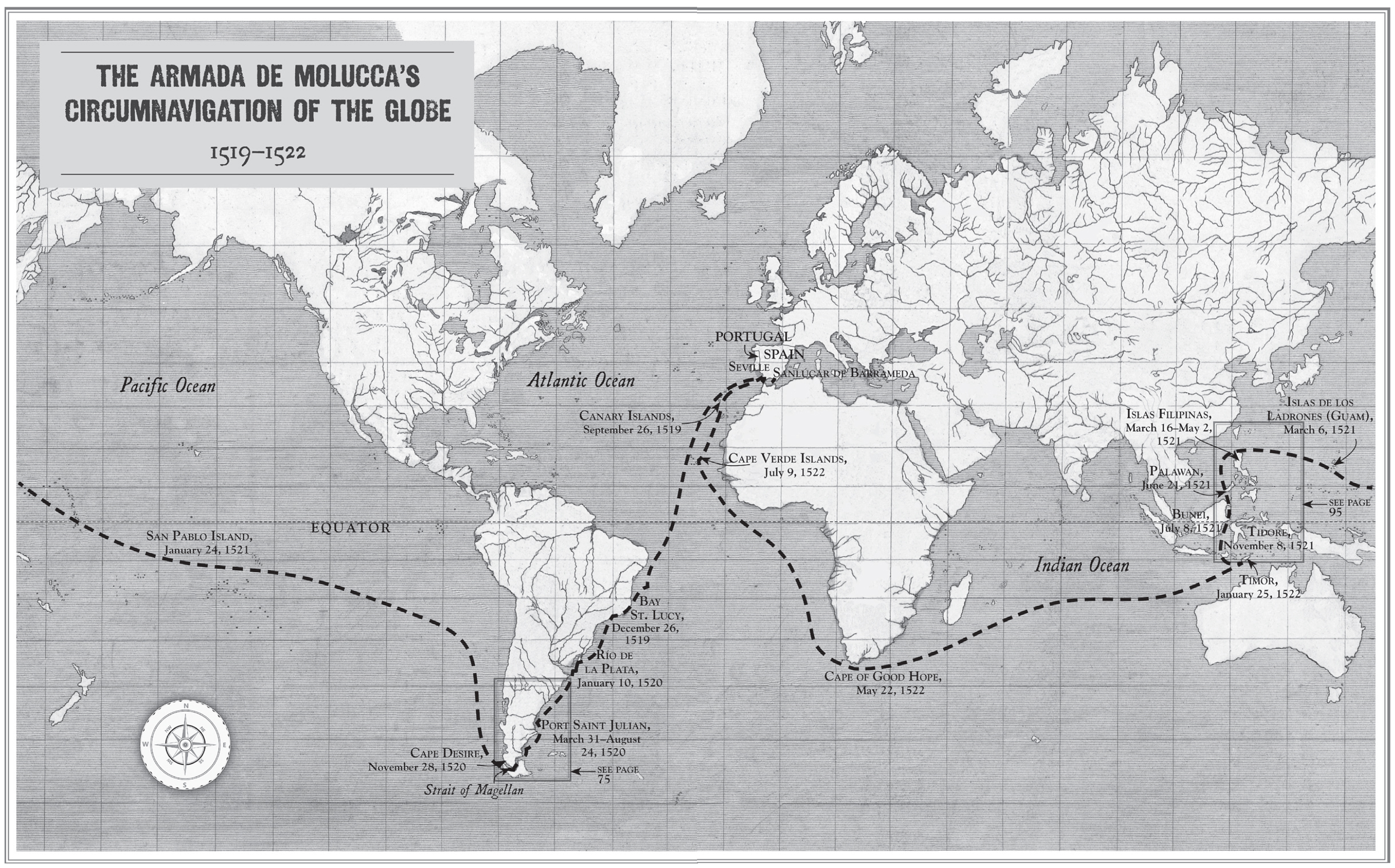

On September 6, 1522, a battered ship appeared on the horizon near the port of Sanlcar de Barrameda, Spain.

As the ship drew closer, people gathered onshore noticed that her tattered sails flailed in the breeze, that her rigging had rotted away, that the sun had bleached her colors, and that storms had damaged her sides. A small pilot boat was dispatched to lead the strange ship over the reefs to the harbor. Those aboard the pilot boat found themselves looking into the face of every sailors nightmare. The vessel they were guiding into the harbor was manned by a skeleton crew of just eighteen malnourished souls suffering from scurvy; most lacked the strength to walk or even to speak. Their tongues were swollen, and their bodies were covered with painful boils. Their captain was dead, as were the officers and the pilots.

Three years earlier, their ship, Victoria , had belonged to a fleet of five vessels manned by 260 sailors under the command of Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese navigator sailing for Spain, with a charter to explore parts of the world unknown to Europeans and claim them for the Spanish crown. The expedition was one of the largest and best equipped ever mounted in the Age of Discovery, the period from around the 1400s to the 1700s, when Europeans began exploring the world by sea. Now Victoria and her ravaged little crew was all that was left, a ghost ship haunted by the memory of the fleets lost sailors. Most had died excruciating deaths, some from scurvy, others by torture, and a few by drowning. Most shocking of all, Ferdinand Magellan himself had been murdered. Despite her brave name, Victoria was not a ship of triumph; she was a ship of agony.

But what a story the survivors had to tell: a chronicle of the most ambitious of all maritime expeditions; a tale of mutiny, of carousing on distant shores, and of exploring the entire globe; a story that changed the course of history and the way people saw the world. These survivors were the first to circumnavigate the entire earth. In the Age of Discovery, many voyages ended in disaster and were quickly forgotten, yet this one, despite the misfortunes that befell it, became the most important maritime expedition ever undertaken. The voyage demonstrated, among other things, that the earth was round, that the Americas were a separate continent (the New World), and that people lived everywhere on the planet. But the cost of these discoveries in terms of suffering and loss of life was greater than anyone could have anticipated. Had its captain, Ferno de Magalhes, whom we call Ferdinand Magellan, conquered the world, or is it more accurate to say the world conquered him?

On June 7, 1494, Pope Alexander VI divided the world in half. The Treaty of Tordesillas established an imaginary line running down the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Everything to the west of the line belonged to Spain, and everything to the east went to Spains chief rival, Portugal. The only exception was Brazil, which Portugal also ruled.

Rather than settling the heated dispute over the New World, recently discovered by Christopher Columbus, the treaty ignited a furious race among nations to claim new lands and control the worlds trade routes. At the time, Europeans were deeply ignorant of the world at large. Under the influence of PtolemyClaudius Ptolemaeus, a Greco-Egyptian mathematician and astronomer who lived in the second century CEastronomers believed that the sun circled the earth. Ptolemys influential work Geography spoke of a magnetic island; if ships sailed too close to it, the nails would be pulled from their hulls and the vessels would sink. Cartography (mapmaking) was often a matter of guesswork. The maps of 1494 depicted a world seamlessly combining heaven and earth. Mixing geography with mythology, adding phantom continents while neglecting real ones, cartographers made images of a world that never was. In the Age of Discovery, more than half the world was unexplored, unmapped, and misunderstood by Europeans. Although men of science and learning agreed that the earth was round, some mariners feared they could literally sail over the edge of the world.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Magellan: Over the Edge of the World»

Look at similar books to Magellan: Over the Edge of the World. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Magellan: Over the Edge of the World and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.