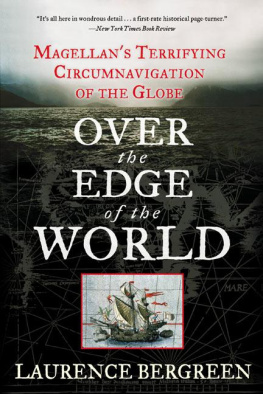

Over the Edge of the World

Magellans Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe

Laurence Bergreen

In memory of my brother and father

How a Ship having passed the Line was driven by storms to the cold Country towards the South Pole; and how from thence she made her course to the tropical Latitude of the Great Pacific Ocean; and of the strange things that befell; and in what manner the Ancyent Marinere came back to his own Country.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

King Charles I (later Charles V, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire)

King Manuel (king of Portugal)

Juan Rodrguez de Fonseca (bishop of Burgos)

Cristbal de Haro (financier)

Ruy Faleiro (cosmographer)

Beatriz Barbosa (Magellans wife)

Diogo Barbosa (Magellans father-in-law)

The Armada de Molucca

(at the time of departure from Seville)

Trinidad

Ferdinand Magellan (Captain General)

Estvo Gomes (pilot major)

Gonzalo Gmez de Espinosa ( alguacil , or master-at-arms)

Francisco Albo (pilot)

Pedro de Valderrama (chaplain)

Gins de Mafra (seaman)

Enrique de Malacca (interpreter)

Duarte Barbosa (supernumerary)

lvaro de Mesquita (Magellans relative, supernumerary)

Antonio Pigafetta (chronicler, supernumerary)

Cristvo Reblo (Magellans illegitimate son, supernumerary)

San Antonio

Juan de Cartagena (captain and inspector general)

Antonio de Coca (fleet accountant)

Andrs de San Martn (astrologer and pilot)

Juan de Elorriaga (master)

Gernimo Guerra (clerk)

Bernard de Calmette, also known as

Pero Snchez de la Reina (chaplain)

Concepcin

Gaspar de Quesada (captain)

Joo Lopes Carvalho (pilot)

Juan Sebastin Elcano (master)

Juan de Acurio (mate)

Hernando Bustamente (barber)

Joozito Carvalho (cabin boy)

Martin de Magalhes (supernumerary)

Victoria

Luis de Mendoza (captain)

Vasco Gomes Gallego (pilot)

Antonio Salamn (master)

Miguel de Rodas (mate)

Santiago

Juan Rodrguez Serrano (captain)

Baltasar Palla (master)

Bartolom Prieur (mate)

D ates are given in the Julian calendar, in effect since the time of Julius Caesar. With modifications, this calendar was adopted by Christian churches around the world, including those in Spain.

Sixty years after the completion of Magellans voyage, in 1582, Spain, France, and other European countries migrated to the Gregorian calendar, decreed by Pope Gregory XIII and designed to correct incremental errors in the Julian system. It took more than two centuries to complete the transition to the new calendar throughout Europe, since Protestant nations resisted the change. To correct for accumulated errors, ten days were omitted, so that October 5, 1582, in the Julian calendar suddenly became October 15, 1582, in the Gregorian.

In addition to this calendar shift, Magellans voyage had its own record-keeping issues. The dates of various events recorded by the two official chroniclers of the expedition, Antonio Pigafetta and Francisco Albo, occasionally diverge by one day. The discrepancy may be due to human error, and it may also have been caused by the way each diarist reckoned the day. Albo, a pilot, followed the custom of ships logs, which began the day at noon rather than at midnight. In contrast, Pigafetta used a nonnautical frame of reference in his diary. Thus, an event occurring on a given morning might have been put down a day apart in the records maintained by the two.

Finally, the international date line did not exist before Magellans voyage. (It now extends west from the island of Guam, in the Pacific Ocean.) As Albo and Pigafetta neared the completion of their circumnavigation, they were astonished to note that their calculations were off, and their voyage around the world actually took one day longer than they had thought.

One fathom equals six feet.

One Spanish league ( legua ) equals approximately four miles.

One bahar (of cloves) equals 406 pounds.

One quintal equals 100 pounds.

One cati (a Chinese measurement) equals 1.75 pounds.

One braza (of cloth) equals about five and a half feet.

One maraved equals approximately 12 modern cents.

Oh! dream of joy! is this indeed

The light-house top I see?

Is this the hill? is this the kirk?

Is this mine own countree?

O n September 6, 1522, a battered ship appeared on the horizon near the port of Sanlcar de Barrameda, Spain.

As the ship came closer, those who gathered onshore noticed that her tattered sails flailed in the breeze, her rigging had rotted away, the sun had bleached her colors, and storms had gouged her sides. A small pilot boat was dispatched to lead the strange ship over the reefs to the harbor. Those aboard the pilot boat found themselves looking into the face of every sailors nightmare. The vessel they were guiding into the harbor was manned by a skeleton crew of just eighteen sailors and three captives, all of them severely malnourished. Most lacked the strength to walk or even to speak. Their tongues were swollen, and their bodies were covered with painful boils. Their captain was dead, as were the officers, the boatswains, and the pilots; in fact, nearly the entire crew had perished.

The pilot boat gradually coaxed the battered vessel past the natural hazards guarding the harbor, and the ship, Victoria , slowly began to make her way along the gently winding Guadalquivir River to Seville, the city from which she had departed three years earlier. No one knew what had become of her since then, and her appearance came as a surprise to those who watched the horizon for sails. Victoria was a ship of mystery, and every gaunt face on her deck was filled with the dark secrets of a prolonged voyage to unknown lands. Despite the journeys hardships, Victoria and her diminished crew accomplished what no other ship had ever done before. By sailing west until they reached the East, and then sailing on in the same direction, they had fulfilled an ambition as old as the human imagination, the first circumnavigation of the globe.

T hree years earlier, Victoria had belonged to a fleet of five vessels with about 260 sailors, all under the command of Ferno de Magalhes, whom we know as Ferdinand Magellan. A Portuguese nobleman and navigator, he had left his homeland to sail for Spain with a charter to explore undiscovered parts of the world and claim them for the Spanish crown. The expedition he led was among the largest and best equipped in the Age of Discovery. Now Victoria and her ravaged little crew were all that was left, a ghost ship haunted by the memory of more than two hundred absent sailors. Many had died an excruciating death, some from scurvy, others by torture, and a few by drowning. Worse, Magellan, the Captain General, had been brutally killed. Despite her brave name, Victoria was not a ship of triumph, she was a vessel of desolation and anguish.

And yet, what a story those few survivors had to tella tale of mutiny, of orgies on distant shores, and of the exploration of the entire globe. A story that changed the course of history and the way we look at the world. In the Age of Discovery, many expeditions ended in disaster and were quickly forgotten, yet this one, despite the misfortunes that befell it, became the most important maritime voyage ever undertaken.

This circumnavigation forever altered the Western worlds ideas about cosmologythe study of the universe and our place in itas well as geography. It demonstrated, among other things, that the earth was round, that the Americas were not part of India but were actually a separate continent, and that oceans covered most of the earths surface. The voyage conclusively demonstrated that the earth is, after all, one world. But it also demonstrated that it was a world of unceasing conflict, both natural and human. The cost of these discoveries in terms of loss of life and suffering was greater than anyone could have anticipated at the start of the expedition. They had survived an expedition to the ends of the earth, but more than that, they had endured a voyage into the darkest recesses of the human soul.