The First Circumnavigators

Magellans fleet

Circling the globe

The First Circumnavigators

Unsung Heroes of the Age of Discovery

Harry Kelsey

Copyright 2016 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations,

in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108

of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press),

without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational,

business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail

(US office) or (UK office).

Set in Janson Roman type by Integrated Publishing Solutions,

Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016930472

ISBN 978-0-300-21778-0 (hardcover)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Judi and Myrna

Contents

ONE

The Voyage of Magellan

TWO

The Voyages of Loaisa and Saavedra

THREE

The Voyage of Villalobos

FOUR

The Voyage of Legazpi

FIVE

Following the Leader

Illustrations and Maps

Introduction

As far back as written records go, the silks and spices of the East made their way to Europe only after a long and arduous journey through Asia to the Mediterranean coast. At that point they came into the hands of Turkish traders and Venetian merchants who sold them to the rest of Europe at a huge profit. By the middle fifteenth century, French, English, Portuguese, and Spanish seamen were working feverishly to find a way to the East that would break this monopoly. But spices and silks were not the only commodities that lured these explorers to Asia. Scholars and geographers still believed that it might be possible to locate the islands of Tharsis and Ophir, where Sacred Scripture reported that Solomons temple builders found their mines of gold and precious gems.somewhere in that unexplored portion of the globe unclaimed by any Christian king. As such, it was an area open for faithful believers to claim.

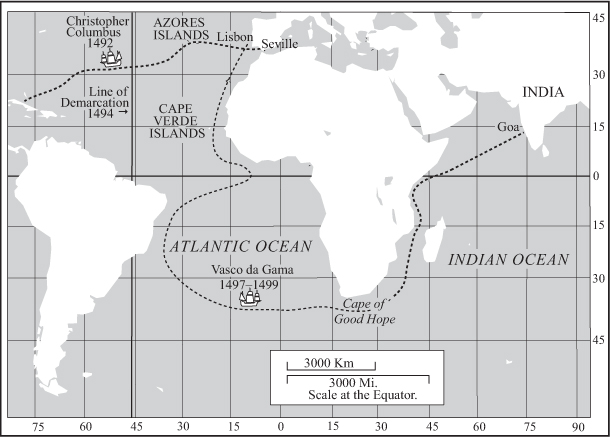

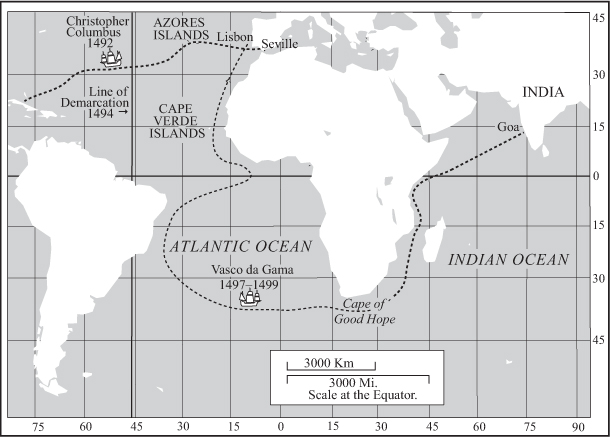

In the final two decades of the fifteenth century, two dramatic discoveries changed everything. Bartholomeu Dias managed to sail around the southern tip of Africa in 14871488, making it possible to reach Asia by sea and avoid the Turkish-Venetian monopolists. His accomplishment was kept secret for a few years so that the route to Asia might be explored. Meanwhile, Castilian seamen began looking for a western route to Asia. When Christopher Columbus returned from his first voyage of discovery, he reported to the Spanish sovereigns that he had reached the Spice Islands by sailing west.

Although it soon became clear that he had done nothing of the sort, the Portuguese and Spanish monarchs decided to divide this newly discovered world between themselves. In a series of treaties signed in 1494 and later they agreed to divide the non-Christian world equally. Spanish mariners would follow the route of Columbus, sailing west on the outward journey and east on the way home. Portuguese ships would continue to sail around Africa and then go east across the Indian Ocean.

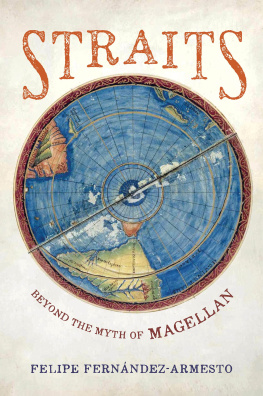

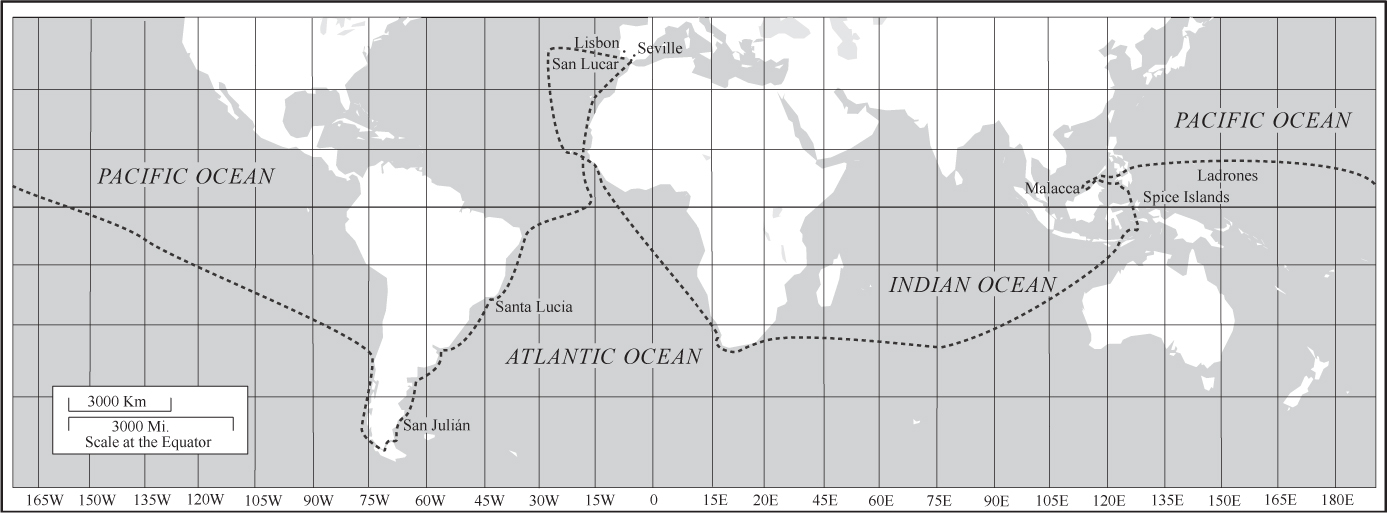

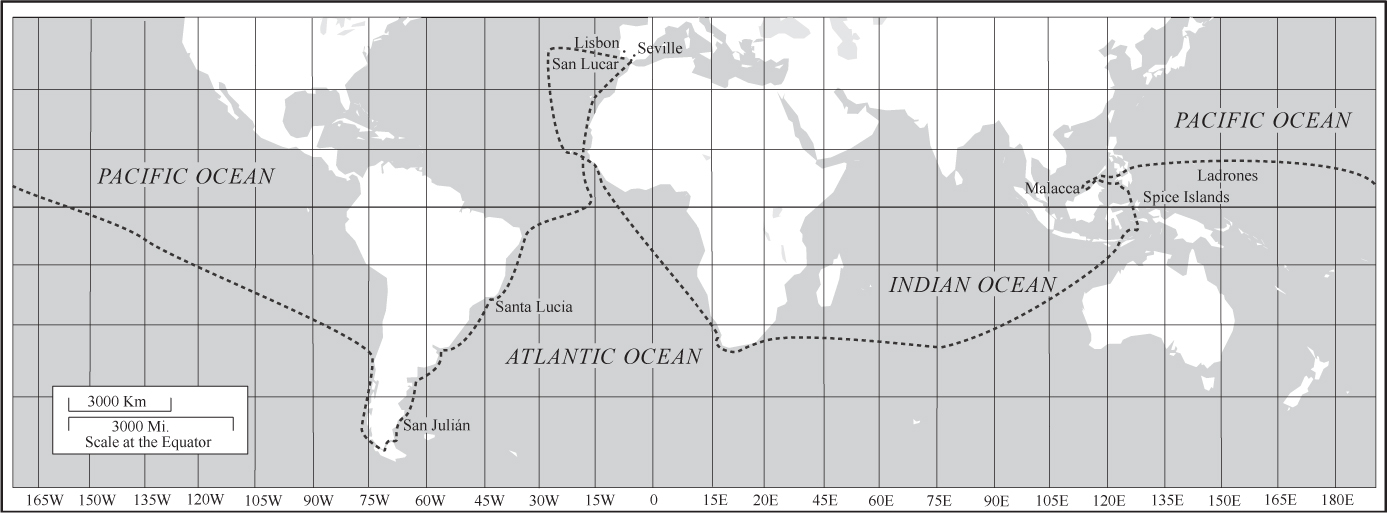

Simple enough in the telling, the trip was complicated by factors of geography that were scarcely suspected before Magellans armada circled the globe in 15191522. Even then, there were decades of dispute before mariners and diplomats began to understand the immense distances involved in the newly discovered continents and oceans. And no one in Spain or Portugal really knew how difficult the problems would be.

The Line of Demarcation, 1494

Even after the reports of Magellans expedition had been subjected to scrutiny by cosmographers in Spain, no one could quite comprehend the vastness of the globe or the broad expanse of the Pacific Ocean. For more than forty years Spanish mariners struggled to discern the winds and currents that controlled the sailing routes on these uncharted waters. The Spanish search for King Solomons treasure islands, for the spice regions, for new lands to rule, and for pagan souls to save prompted Spanish mariners to study these problems and led to the discovery of a round-trip route across the Pacific and back to New Spain, one of the major navigational feats of the sixteenth century. But in the process dozens of men became circumnavigators of the globe. And some sailed around the world more than once, an astonishing achievement in that age of exploration.

The various Spanish voyages of discovery in this era were not entirely separate and distinct enterprises. Each successive Spanish commander used charts and logs and employed mariners from previous armadas. In addition, the Spanish government maintained an official map corpus in Seville, the padrn general. Showing the latest discoveries, or at least those that were known from competent, firsthand evidence, these maps were available to all Spanish pilots. In fact, their use was required on Spanish vessels. As a result, Spanish pilots and mariners were able to develop an increasingly accurate understanding of the unknown winds and uncharted currents of the Pacific. Even so, it took nearly half a century to find the way west from Europe to the Indies and back again.

The story begins with Ferdinand Magellan, a mariner who had made the trip to the Portuguese Indies and spent several years in the islands. When he returned to Lisbon, Magellan thought that he had earned the right to command his own expedition and asked the king of Portugal to let him do so. When the king refused, Magellan took himself and a group of relatives and friends to Spain, where he convinced young King Charles to put him in charge of a Spanish fleet, to be manned in great part by Portuguese seamen.

Magellan and the captains who followed him are more or less well known, and their accomplishments are celebrated in historical studies, pictures, and monuments. But the men who manned the shipsthe seamen, soldiers, and adventurers who made it all possible and lived to tell the talehave remained largely anonymous.

Some of their names are known. Others are not. Even their numbers have been in dispute. According to the most popular studies, only eighteen of Magellans men made it home. But the truth is that more than forty of them circumnavigated the globe. The stories are similar for the Loaisa and Saavedra expeditions, in which one man circled the globe for the second time. On the other hand, several accounts suggest that more than a hundred men came home from the Villalobos expedition, when scarcely twenty actually did so. This book attempts to identify these unsung heroes. They were the first people to sail all the way around the world, but they did so unintentionally, for there was no other way to return home. They were accidental circumnavigators.

Here are a few words of warning to unsuspecting readers:

First, sixteenth-century Spanish name usage was not the same as that followed today. The first surname was not necessarily that of the father, nor was the second that of the mother. In fact, there might be only one surname and that might be something entirely different from the names of the parents. And nomenclature was often decided by popular usage or personal preference. Thus Ruy Lpez de Villalobos might be referred to in that way or as Villalobos, but not as Lpez de Villalobos. In the same way Juan Rodrguez Cabrillo was called Juan Rodrguez and sometimes Cabrillo, but not Rodrguez Cabrillo. Adding to the confusion, some people had no family names, never having found a need for them. Until enlistment. Names are important for pay records, so a man enlisting for a voyage might be enrolled by the name of his village or his province or country. Later, he might decide to adopt a different name, sometimes being listed one way, sometimes another. The names employed in this study are as nearly as possible the ones used by the men themselves, with variations listed as necessary.

Next page