Charles V

Charles V

The World Emperor

Harald Kleinschmidt

First published in 2004 by Sutton Publishing

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

Harald Kleinschmidt, 2004, 2012

The right of Harald Kleinschmidt, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7440 3

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7439 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

List of Abbreviations

Cal. Venice | Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts, Relating to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice and in Other Libraries of Northern Italy, ed. Rawdon Brown et al. (London, 1864). |

Kohler, ed., Quellen | Quellen zur Geschichte Karls V., ed. Alfred Kohler (Darmstadt, 1990) (Ausgewhlte Quellen zur deutschen Geschichte der Neuzeit, 15). |

Lanz, ed., Correspondenz | Correspondenz des Kaisers Karl V. Aus dem Kniglichen Archiv und der Bibliothque de Bourgogne zu Brssel, 3 vols, ed. Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Lanz (Leipzig, 184446) [repr. (Frankfurt, 1966)]. |

Lanz, ed., Staatspapiere | Staatspapiere zur Geschichte Kaiser Karls V. Aus dem Kniglichen Archiv und der Bibliothque de Bourgogne zu Brssel, ed. Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Lanz (Stuttgart, 1845) (Bibliothek des Litterarischen Vereins, 11). |

LP | Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Relating to the Reign of Henry VIII, ed. John Sherren Brewer et al., 22 vols (London, 18621930). |

MGH, SS | Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores |

MGH, SS rer. Merov. | Monumenta Germanie Historica, Scriptores rerum Merovingicarum |

RTA 1 | Deutsche Reichstagsakten. Jngere Reihe, vol. 1, ed. August Kluckhohn (Gotha, 1893). |

RTA 2 | Deutsche Reichstagsakten. Jngere Reihe, vol. 2, ed. Adolf Wrede (Gotha, 1896). |

RTA 7 | Deutsche Reichstagsakten. Jngere Reihe, vol. 7, ed. Johannes Khn (Gttingen, 1962). |

RTA 8 | Deutsche Reichstagsakten. Jngere Reihe, vol. 8, ed. Wolfgang Steglich (Gttingen, 1970). |

SP Spain | Calendar of Letters, Despatches, and State Papers Relating to the Negotiations between England and Spain, preserved in the Archives at Simancas, Vienna, Brussels, and Elsewhere, ed. G.A. Bergenroth et al., 14 vols (London, 18621940). |

Weiss, ed., Papiers | Papiers dtat du cardinal de Granvelle daprs les manuscrits de la bibliothque de Besanon, 9 vols, ed. Charles Weiss (Paris, 184143). |

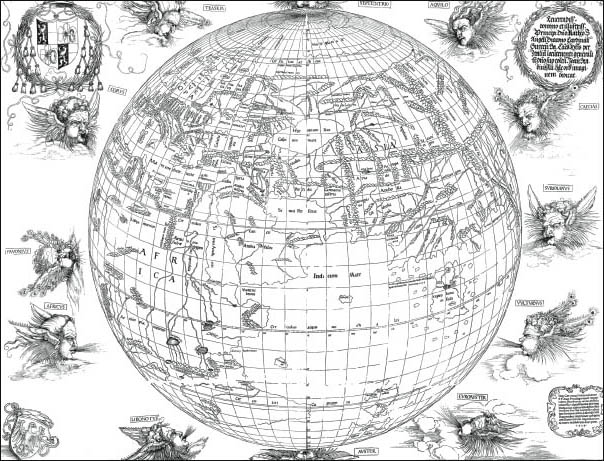

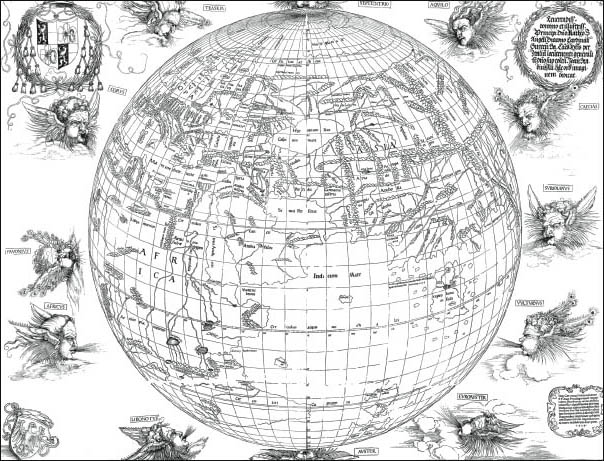

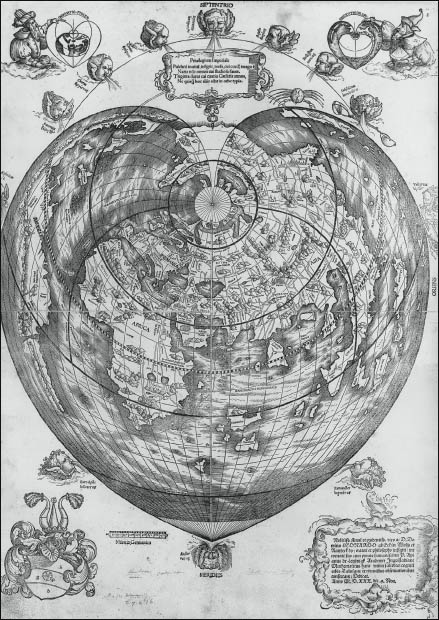

Stabius-Drer, map of the world, 1515. (London, British Library)

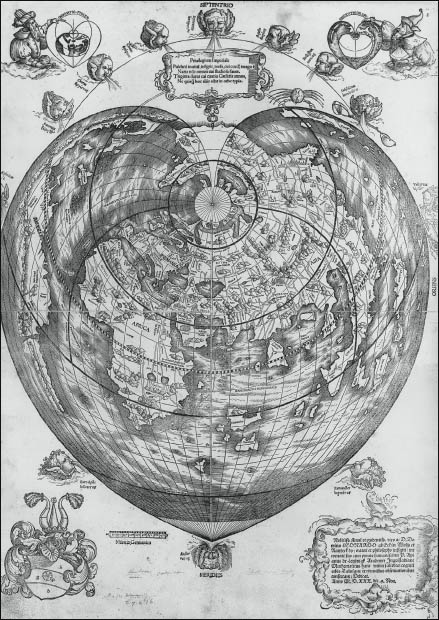

Peter Apian, map of the world, 1530. (London, British Library)

Introduction

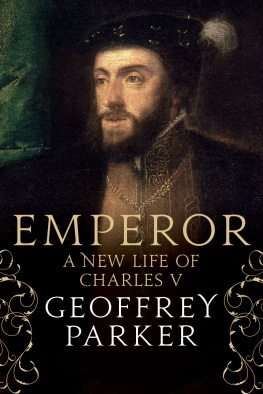

P eter Paul Rubenss portrait of 1635 eternalises Emperor Charles V as a warrior and as a world emperor. Wearing a laurel wreath and dressed in full armour underneath a tunic, Charles holds a globe (sphaira) in his left hand and a sword in his right. He extends his right hand and presents the sword with its blade upwards but pushes the globe towards his chest. He appears to be ready to strike with his right hand while seeking to protect the globe against an attack.

Rubens drew on the medieval occidental iconography of emperors. From the tenth century occidental rulers bearing the imperial title were often shown holding the sphaira as the symbol of universal rule in their extended left hand and the sceptre as the symbol of virtue and equity in their extended right hand. Rubens modified the medieval model in two important respects: he replaced the symbol of virtue and equity by the symbol of war-proneness and did not allow Charles to extend his left hand. Rubenss portrait thus visualises a tension between Charles as a daring warrior and Charles as the peace-bringing emperor. Readiness to use military force and willingness to protect the world do not seem to go together.

Rubenss portrait is part of a tradition of scepticism that constitutes a conflict between the tasks of a warrior and the tasks of a ruler; that juxtaposes the values of heroism against the values of stoicism; that recognises the obligation of warriors to risk their lives while it imposes upon rulers the obligation to preserve their lives as long as they can. Again, the tradition is old. It can be traced back to the tenth century. But did Charles himself accept the view that there was a conflict between warriors and rulers norms, values and rules? Certainly, some of his advisers urged him not to risk his life, and Charles died peacefully, though not as a ruler. Yet he consciously risked his life on several occasions, was trained in combat, acted as a military commander and reflected on aspects of the theory of war. Contrary to the legacy of the medieval tradition of rulers ethics Charles combined rather than juxtaposed warriors and rulers norms, values and rules. This book will show that Charles saw the fulfilment of his warrior tasks as the precondition for the accomplishment of his obligations as a ruler. War was an element of life, peace a dream about the future at best. Although he lived with medieval traditions, Charles was not a man of the Middle Ages.

Charles was born as a Burgundian nobleman at Ghent in the Netherlands on 24 February 1500. He took the office of the duke of Burgundy at the age of six. He succeeded as ruler of the Spanish kingdoms in 1516 and was elected emperor in 1519. As a young man Charles raised the most exalted hopes: that he could unify Christendom and that he could pacify the world. Indeed, he journeyed back and forth between the Iberian peninsula and central Europe attempting to bring peace and good government to his many subjects. But, after forty years in office, his many foes denounced him as the butcher of Flanders and nicknamed him Charles of Ghent who claims to be emperor. At the age of fifty-five he felt ill and so tired that he abdicated and spent his remaining years in the vicinity of a monastery, where he died in 1558.