Harry Kelsey is the author of Sir Francis Drake: The Queens Pirate and Sir John Hawkins: Queen Elizabeths Slave Trader.

Philip as King of England has hitherto been a rather overlooked figure in English history. This book is a timely attempt to place him centre stage. Anna Whitelock, author of Mary Tudor: Englands First Queen.

Published in 2012 by I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

Copyright 2012 Harry Kelsey

The right of Harry Kelsey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 84885 716 2

eISBN: 978 0 85773 034 3

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Designed and typeset by 4word Ltd, Bristol

Illustrations and Maps

Illustrations

Maps

Illustration Credits

All of the outline maps were made by the author. Other illustrations are from the collections of the Huntington Library, except as noted below:

Fig. 5 Museo del Prado, Madrid, P00415.

Fig. 8 National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 428.

Fig. 15 Knight, Charles. History of England (London: 1878).

Fig. 16 Negri, Francesco. A secretis Senatus Mediolanen. Britannicar. Nuptiar (Mediolani: 1559)

Fig. 17 Flaherty, William. Annals of England (Oxford, 1876).

Fig. 19 Law, Ernest. History of Hampton Court Palace (London: 1891).

Fig. 22 Nichols, John. Chronicle of Calais (London: 1846).

Abbreviations

AGS | Archivo General de Simancas |

AGI | Archivo General de Indias |

BL | British Library |

CDIE | Coleccin de documentos inditos para la historia de Espaa |

HMC | Historical Manuscripts Commission (National Archives) |

ODNB | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |

PRO | Public Record Office (National Archives) |

Preface

When Mary Tudor came to the English throne in 1553, she was a spinster, somewhat elderly (late thirties) for the time, and anxious to restore the practice of the Catholic faith that had been her one consolation during a bitterly conflicted youth. Much earlier, while she was still a child, Mary had been promised in marriage to her cousin Charles, who was both King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor. Now facing old age, Charles suggested that she instead marry his son. Philip was a widower, more than ten years Marys junior, and currently serving as regent during his fathers absence from Spain. Mary accepted, an agreement was signed, and in the course of time Philip and Mary were married. Thus began a curious period when a Spanish king shared the throne of England.

This study began during research for biographies of Sir Francis Drake and his cousin Sir John Hawkins. Both sailed in English ships when Philip was King of England. Drake later gained fame as Philips archenemy. Hawkins, somewhat older than his cousin, claimed to have served Philip and later became deeply involved in curious negotiations with Philip over men in his fleet who languished in Spanish prisons. If all this arouses your curiosity, it certainly did the same for me, and I resolved to find out more.

The research was made possible through generous grants from the Giles W. and Elise G. Mead Foundation and the support of my own institution, the Huntington Library. Much of the material comes from the superb rare book and manuscript collections of the Huntington, as well as the British Library, and various other institutions. Other materials were consulted in Spanish archives, most notably the Archivo General de Simancas, whose staff do everything possible to make historical research a pleasure.

Several scholars have made helpful suggestions, including Robert T. Smith and Robert Keane. Robert Ritchie read the entire manuscript, as did Joanna Godfrey; both of them offered corrections and otherwise kept me from embarrassing errors.

Introduction

The maestre de campo ordered the firing of muskets and arcabuces. When the enemy saw this, they fired back. Our own men called them cowards and said ugly things about their lack of spirit, calling them Lutheran chickens.

Pedro Coco Caldern

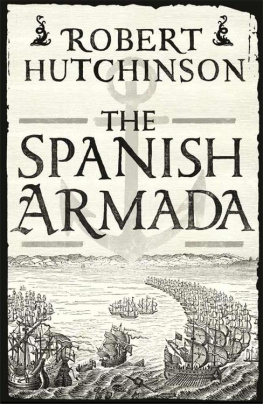

On the morning of 20 July 1588 English lookouts standing on the cliffs near Plymouth spotted a great Spanish armada sailing up the coast. There were perhaps 130 ships, the largest fleet assembled in the Channel in more than thirty years. The Great Armada was a message of war sent by King Philip of Spain.

As the Spanish fleet made its way up the coast there were running fights and losses on both sides, including Francis Drakes capture of a Spanish pay ship. But the first real battle came on the twenty-ninth in the roadstead off Calais, with gunners on both sides firing at such close range that cannoneers could shout and curse at their enemies while reloading for another shot. For nine hours the battle raged, while the fleets drifted east between Gravelines and Ostend.

In the course of the battle both the Spanish and the English ships felt for the first time the real effect of the enemy artillery. The Spanish flagship took more than a hundred hits in her hull, masts, and sails, with several shots below the waterline that caused serious leaks. Two Spanish galleons, hoping to grapple with the enemy, worked their way past the battle line and into a nest of English ships. In the melee one galleon had five guns put out of action, decks very nearly destroyed, pumps broken, and rigging in shreds. Nevertheless, her captain broke out the grappling hooks and challenged the English sailors to come alongside for a fair fight. When they would not, his crew shouted out that they were cowards and Lutheran chickens and drove the English ships away with musket fire. There was serious damage on the English side as well, but luck was on the English side.

At the end of the fight most of the Spanish ships were in reasonably sound condition, but the invasion army that was to meet the fleet on the coast was not ready. Consequently the Spanish commander had to abandon the plan to invade England. During the next week the Spanish Armada was caught in the fierce Channel winds and driven into the North Sea where the real destruction began. Battered by storms, the ships made their way northward around Scotland. About half of the Armada was lost on the long voyage home, many driven ashore on the coasts of Scotland and Ireland. Thus, by hard fighting and good luck an English fleet managed to end the threat of invasion by the Spanish king who had once been King of England.