WARRIOR 131

NELSONS OFFICERS AND MIDSHIPMEN

| GREGORY FREMONT-BARNES | ILLUSTRATED BY STEVE NOON |

Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic

CONTENTS

NELSONS OFFICERS AND MIDSHIPMEN

INTRODUCTION

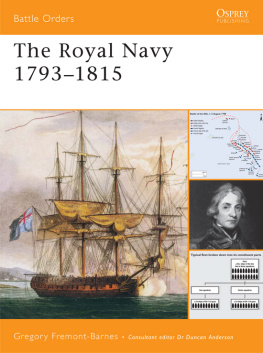

In the course of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (17931815) and the Anglo-American War (181215), officers of the Royal Navy came to rank amongst the most respected members of British society, a consequence of their extraordinary record of leadership over the course of two decades of conflict against a host of adversaries, including the French, Spanish, Dutch, Danes and Americans. Whereas the Army had always been regarded as a suitable place for an aristocrats son, this was not so in the Navy until the mid-18th century. Younger sons tended to join the church, Parliament or seek employment in the law, since the eldest son inherited the family estate. Thus, the Navy was a natural option for such young men, together with the sons of the growing middle class. Unlike in the Army, where commissions were attained by purchase, a high degree of professional skill was required in the Navy. As a consequence, naval officers and midshipmen were nearly always more competent and professional than their Army counterparts, and, since money played considerably less of a part in the process of promotion, the Navy naturally attracted men from a wider social background than the Army. Such men who attained in the course of a generation a status not enjoyed either before or since form the study of this short work, which will focus on their training, uniforms and equipment, daily life, pay, responsibilities aboard ship and experiences in and out of battle.

A young man seeking a Navy commission, before going to sea as a midshipman, might spend a short time at the Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth, though educational standards were indifferent, and most of what he learned he acquired at sea under the tutelage of the ships schoolmaster or chaplain, who received extra pay for tutoring a boy for one or two hours a day, usually in mathematics and navigational skills. The young lad usually spent six years at sea before sitting the lieutenants exam at the age of 20 or more. If he passed, he received a commission and began the long climb up the promotional ladder, a process that could be accelerated by deaths at sea from sickness, disease or battle, or from the process of patronage that, notwithstanding the inability to purchase a commission or command, nevertheless rendered the Navy far from egalitarian. If he passed the exam for lieutenant and a vacancy existed he might receive an independent command aboard a sloop or brig, before eventually reaching the lofty rank of captain, which entitled him to command a frigate and, after further years of good service or connections, perhaps a ship of the line.

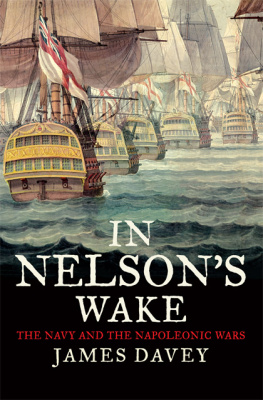

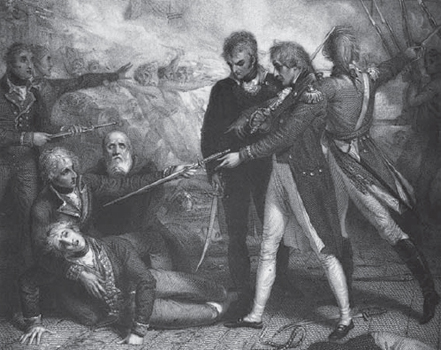

Nelson falls mortally wounded on the quarterdeck of the Victory at Trafalgar. Marines and Captain Hardy come to his aid, while in the centre foreground a midshipman takes aim at a French marksman in the rigging of the Redoutable, which lay to starboard. (National Maritime Museum)

The captains range of responsibilities extended from the ship herself to the entire crew. He oversaw everything from the maintenance of discipline and hygiene to the allocation of food and accommodation. He not only possessed the authority to promote or punish, but in fact wielded more power than the king himself, for while a captain could order a man to be flogged, his sovereign could not. It was the captain who decided when and where battle should be joined thus placing in his hands the power of life and death over the ships company. In exchange for all these rights and responsibilities, he regularly risked his own reputation and life, with compensation in the form of higher pay, a greater proportion of any prize money than his subordinates and quarters of greater extent than those of all his lieutenants combined. In most cases he held his crews respect, which manifested itself by high morale, skilled seamanship, a high standard of gunnery and a willingness to exert and sacrifice themselves for the captain, quite apart from king and country, as Admiral Sir Robert Calder recalled of his time as a ships captain:

When I commanded a single ship it was my chief delight to have the goodwill of my men, and I can safely assert evry man under my orders would freely lay down their life to obey me or my commands, and by such means I made my crew both love and fear me. They loved me for my humanity and feard to cause my displeasure, and this I found the best school for seamen. They will fight for you and if required die for you.

A captain of this description together with others possessing fewer virtues but greater connections with those of influence might, if fortune served him well and infirmity and death eluded him, achieve a foothold on the ladder of promotion, up which greasy pole he would painstakingly negotiate his way from rear to vice, to full admiral, commanding as he went a squadron of half a dozen ships of the line or perhaps a fleet of 20 or more.

CHRONOLOGY

| 1793 | The French Revolutionary Wars having begun the previous year, Britain joins Austria and Prussia in opposing France, bringing the full power of the Royal Navy to bear at sea while the Allies fight on land (1 February). |

| 1794 | In the first fleet action of the war, Admiral Lord Howe defeats the French off Ushant (1 June). |

| 1795 | Spain abandons the First Coalition and concludes a treaty of alliance with France against Britain, throwing her substantial fleet into the scales and forcing the Royal Navy to abandon the Mediterranean (19 August). |

| 1797 | Admiral Sir John Jervis vanquishes the Spanish at St Vincent (14 February), while the Channel Fleet defeats a Dutch force at Camperdown (11 October). Serious mutinies break out at Spithead (16 April) and the Nore (12 May) affecting the Channel and North Sea fleets, respectively. |

| 1798 | After fruitlessly searching the Mediterranean for the French fleet conveying Bonapartes army to Egypt, Nelson finally discovers it anchored in Aboukir Bay, near Alexandria, where he annihilates it, leaving the French stranded without hope of reinforcement or withdrawal (12 August). |

| 1801 | Seeking to oppose neutral powers limitations on British naval and commercial access to the Baltic Sea, the Admiralty dispatches a naval force to confront the Danish Fleet, which Nelson, albeit at significant loss to his own force, drubs at Copenhagen (2 April). |

| 1802 | After a decade of conflict in Europe, a fragile peace is established by the Treaty of Amiens, bringing an end to the French Revolutionary Wars (30 March). |

| 1803 | After French interference in the internal affairs of Switzerland and Holland, Britain refuses to evacuate Malta, as agreed at Amiens, as a counterweight to growing French hegemony on the Continent. Her declaration of war inaugurates a new series of conflicts known as the Napoleonic Wars (18 May). |

| 1804 | Irritated by Spains ostensible neutrality but partiality toward France, Britain seizes a Spanish treasure fleet bound from Montevideo, provoking a declaration of war from Madrid (12 December). |

| 1805 | In the most decisive naval encounter in history, Nelson confronts a combined French and Spanish fleet off Cape Trafalgar, capturing or destroying over half the enemys force and thus safeguarding Britain from invasion for the remainder of the war (21 October). |

Next page