WARRIOR 164

RAF FIGHTER COMMAND PILOT

The Western Front 193942

| MARK BARBER | ILLUSTRATED BY GRAHAM TURNER |

| Series editor Marcus Cowper |

CONTENTS

RAF FIGHTER COMMAND PILOT THE WESTERN FRONT 193942

RAF FIGHTER COMMAND IN THE INTER-WAR PERIOD

When war broke out in 1939, not only was the Royal Air Force (RAF) the junior service among Britains military forces, but military aviation was still in its infancy, and the era before manned, powered flight was still well within living memory. The RAF had been formed in the closing stages of World War I, when the Royal Naval Air Service and the Armys Royal Flying Corps were amalgamated on 1 April 1918. The 59 fighter squadrons, or scout squadrons as they were then known, were based along the Western Front, with a further 16 tasked with defending the home front. Immediately following the Armistice, the RAF, like the other services, experienced enormous cutbacks as the military stepped down from a war footing and the vast majority of service personnel returned to civilian life. The RAF was reduced from being the worlds largest air force at its inception, with some 290,000 personnel and 3,500 aircraft, to losing 90 per cent of its manpower in the post-war demobilization. Peacetime strength was planned at less than 30,000 officers and other ranks and, by 1920, the RAF consisted of only 25 squadrons of all types of aircraft.

The vast war-weariness that swept across the nation in the post-war years permeated parliament, leading to the Ten Year Rule guideline. This was adopted by the British Government in August 1919 and stated that the armed forces should be formed and maintained on the assumption that the British Empire would not be involved in any major wars for the next decade. This had as much a profound effect on the fighter arm of the RAF as on every branch of all three services by the late 1920s, technological development of fighter aircraft had slowed to such a pace that the vast leaps made during World War I were reduced to a mere trickle. The Sopwith Camels and SE5as that the RAF used at the time of the Armistice had been replaced only by Gloster Gamecocks and Bristol Bulldogs open-cockpit biplanes with a similar armament and only marginally superior performance to their Great War ancestors. There had been some optimism for the fighter squadrons of the RAF in April 1923, when recommendations by the SteelBartholomew Committee on the Air Defence of Great Britain led to the establishment of a strength of 52 squadrons for Home Defence, 17 of which would be fighter squadrons. These would fall under the command of the Air Defence of Great Britain (ADGB) that was established in 1925 under Air Marshall Sir John Salmond. However, the 52 squadron plan was deferred. Originally to be implemented with as little delay as possible in 1923, two years later it was judged far less urgent, and put back to 193536. Furthermore, the low number of fighter squadrons within the total plan indicated a clear and obvious preference for funding bomber squadrons. This was articulated in November 1932 during Stanley Baldwins famous speech to the House of Commons: In the next war you will find that any town within reach of an aerodrome can be bombed within the first five minutes of war to an extent inconceivable in the last war. I think it is well also for the man in the street to realise that there is no power on earth that can protect him from being bombed, whatever people may tell him. The bomber will always get through.

Hampered by the global depression, the plan was delayed again in December 1929, and then again in May 1933, by which time the first stirrings of another major war were beginning as Adolf Hitler had been democratically elected in Germany only two months previously. By 1934 Germany was emerging as a clear threat, with British Intelligence well aware of Hitlers rearmament programme in defiance of the limitations laid down by the Treaty of Versailles. Britain finally began plans for a more effective rearmament, although for the RAF this would still be dominated by the bomber. In July 1934 the British government adopted the new Scheme A, which planned for 84 squadrons, 28 of which would be fighter squadrons, to be effective by March 1939. Scheme C came into effect in May 1935, and called for 123 squadrons, including 35 fighter squadrons, to be in service by the end of March 1937. Critically, Scheme C also radically altered the entire command and control structure of the RAF to enable functional and administrative control over the newly proposed strength. The ADGB was dissolved and four new Commands were created: Training, Coastal, Bomber and Fighter.

Promoted to Air Chief Marshall in 1937, Hugh Dowding commanded RAF Fighter Command at the outbreak of the war. Here photographed as an officer in the Royal Flying Corps during World War I, Dowding had experience of front-line squadron command. (RAF Museum, PO23092)

Fighter Command became operational on 14 July 1936, under Air Marshall Sir Hugh Dowding at RAF Bentley Priory. Dowding had commanded No. 16 Squadron RFC on the Western Front during World War I, but after altercations with General Hugh Trenchard, overall commander of the RFC, Dowding spent the last two years of the war in Great Britain, albeit with the rank of brigadier. Dowdings new Fighter Command was made up of four groups No. 11 and No. 12 (Fighter) Groups, No. 22 (Army Co-operation) Group and the Observer Corps. Dowding made two major contributions to the development of Britains aerial defence. First, he pushed for the development of modern, fast and heavily armed fighters to replace his force of soon-to-be-obsolete biplanes. Dowding engaged in talks with Hawker and Supermarine about the need for a modern, fast, monoplane fighter effectively to combat the worrying reports of world-class fighters and bombers being developed in Germany. He also developed Britains network of fighter defence, which would become known as the Dowding System. This involved heavy investment in Radio Direction Finding (RDF) or radar as it would become known partnered with the Observer Corps and command centres to build a picture of incoming threats before effectively controlling Fighter Command via raid plotting and radio control. Although he had his critics, Dowdings system would soon be proved absolutely integral to the defence of the entire nation.

Indicative of the technological standard of aircraft employed by the RAF throughout the inter-war period, the Bristol Bulldog was an open-cockpit, fixed undercarriage, two-gun biplane with a fixed pitch propeller. Still equipping squadrons into the 1930s, the Bulldog was similar in many respects to its Great War predecessors. (RAF Museum, PC71-66-83)

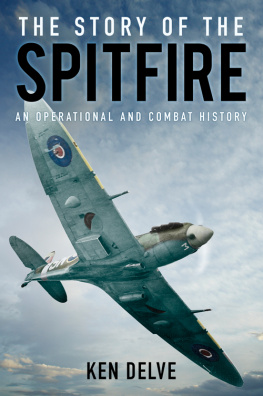

When Dowding took charge of the new Fighter Command he controlled a mere 18 fighter squadrons equipped with open-cockpit, two-gun biplanes. While the development of the fighter had still not come a long way since 1918, Britain was by no means alone in its stagnancy. While also rushing to develop a modern, monoplane fighter, in early 1936 Germany was employing similar types of aircraft to the RAF. All this was about to change for both nations; the eight-gun, monoplane Hawker Hurricane had carried out its initial test flight on 6 November 1935 and on 3 June 1936, the Air Ministry placed orders for 600 Hurricanes for Fighter Command. Only shortly behind chronologically was the Supermarine Spitfire, whose first prototype was flown on 5 March 1936 in response to Air Ministry Specification F.5/34, calling for an eight-gun, enclosed cockpit, retractable landing gear, monoplane fighter the same call to arms which had spurred Hawker into action. F.5/34 demanded, in effect, a fighter to shoot down bombers. Speed, rate of climb and firepower were essential, whereas manoeuvrability was secondary. Scheme F approved on 25 February 1936, promised to deliver 123 squadrons to the RAF by the end of March 1939; 30 of these would be fighter squadrons, made up of 500 Hurricanes and 300 Spitfires.