FIGHTER AIRCRAFT COMBAT DEBUTS,

19151945

Innovation in Air Warfare Before the Jet Age

JON GUTTMAN

Frontis: Republic P-47C-2RE Thunderbolts of the 62nd Squadron, 56th Fighter Group, embark on a bomber escort mission from Horsham St. Faith, England, on May 25, 1943. (US Air Force)

2014 Jon Guttman

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Westholme Publishing, LLC

904 Edgewood Road

Yardley, Pennsylvania 19067

Visit our Web site at www.westholmepublishing.com

ISBN: 978-1-59416-591-7

Also available in hardback.

Printed in the United States of America.

CONTENTS

ONE

First Blood: The Earliest Fighters, 191416

TWO

Biplanes, Boelcke, and the Baron: Halberstadt and Albatros Scouts, 191617

THREE

A Deadlier Breed: Fighter Development, 191617

FOUR

The Triplane Craze: Sopwith Triplane and Fokker Dr. I.

FIVE

Glimpses of Things to Come: Fighters of 1918

SIX

A New Generation: Fighters of the Spanish Civil War, 193639

SEVEN

First Shots of a Second World War: Czechoslovakian, Polish, German, French, Dutch, and Yugoslav Fighters, 193941

EIGHT

The Immortals: Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire, 193941

NINE

Zero Hour: Japanese Fighters, 193741

TEN

Under Foreign Management: Licensed and Leased Fighters, 193942

ELEVEN

The Tide-Turning Generation: American Fighters, 194143

TWELVE

Illustrious Beginnings: Fairey Fulmar and Firefly, 194044

THIRTEEN

The Axis Strikes Back: German, Italian, and Japanese Fighters, 194144

FOURTEEN

Red Resurgence: Soviet Fighters, 194144

FIFTEEN

Aerial Supremacy Over the Islands: Vought F4U Corsair and Grumman F6F Hellcat, 1943

SIXTEEN

Heavy Hitters: Cannon-Armed Fighters, 194044

SEVENTEEN

Dueling in the Dark: Night Fighters, 194044

EIGHTEEN

Odds and Ends: Improvisations and Developmental Dead Ends, 194045

NINETEEN

Dawn of a New Era: Messerschmitt Me 262, Gloster Meteor, and P-80 Shooting Star, 194445

FOREWORD

Of all military aircraft, fighters hold the most mystiqueperhaps because of all military aircraft, fighters are the type that can afford the least compromise. There have been numerous occasions when desperate combatants managed to achieve a surprising degree of success by improvising the most unlikely available aircraft into bombers, attack planes, and reconnaissance aircraft. There is far less room for ingenuity in the realm of fighter planes. When the goal is to seize and maintain control of the air, the confrontation is direct, with the prospect of only one out of two possible outcomes. If a pilot and his plane are better, he and his side wins; if his enemy is superior, he losesand often dies.

Although aircraftin the form of balloonshave appeared in battle since 1794, the concept of air superiority dates to 1914, during World War I. Since then, the development of fighter aircraft has been an ongoing seesaw battle in itself, with each new design leading to another. Like sports cars, fighter planes became sleeker and their performance greater as the competition intensifiedbut in contrast to peacetime competition, they also became deadlier. And with each new development, the pilots had to adjust to higher speeds and higher gssomething they did not always do ungrudgingly. The alternative, however, was to suffer the fate of those seat-of-the-pants Italian fighter pilots who were loath to give up open cockpits, or of the Japanese who regarded dogfighting ability as the primary determinant of a fighters worthin both cases, these aircraft were literally left behind by newer, faster opponents.

Aside from the adrenaline rush of aerial combat itself, a great cause of excitement among fighter pilots is the arrival of a new airplane. As they admire its lines, the questions fill their minds: Will it be all that the manufacturer claims it will be? Will I be able to adjust to its idiosyncrasies? Above all else, will it give me the edge I need to win?

This book explores the first military actions for a variety of famous fighters of World War I, the conflicts of the so-called interwar years, and World War IIa thirty-year period that saw the birth of the fighter concept and its maturity on the threshold of the jet age. Comparisons of the strengths and weaknesses of fighter aircraft will probably go on as long as there are men who will fly them. This study, however, will compare them from a somewhat narrower perspective: How did they do at the very onset?

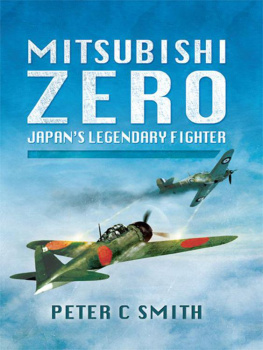

Most of the aircraft described are fairly well known to aviation historians, and a few names, such as Sopwith Camel, Fokker Triplane, Messerschmitt Me 109, Mitsubishi Zero, North American Mustang, and Supermarine Spitfire, are familiar even to the most nonaviation-minded layman. Not so well known are the circumstances of their combat debuts, in which some, such as the Zero, made their mark almost from the outset, but in which others, like the Bristol F.2A, showed rather less promise than they would ultimately realize.

While a certain amount of space must be devoted to the technical development of these famous fighters, these studies of first combats serve as a reminder that it is the human factor, with all its special quirks, that inevitably came into play when these deadly flying machines first fired their guns in anger. It was the pilot who determined how a new airplane did, and the results were not always in direct relation to the planes capabilities. To cite a particularly striking example, the Brewster Buffalo, long vilified for its wretched performance against the Japanese Zero and Hayabusa fighters in the Pacific, actually saw combat for the first time over Finland nearly half a year earlierand, thanks to the skill of the Finnish pilots, enjoyed a generous measure of success over its Soviet opponents that its American and British users would have found unbelievable.

Some of the pilots became as famous as the aircraft they flew, and some of the first men to fly the fighters recounted in this volume are exactly those whom the lay reader would expect. For example, the first aerial victory scored in a Fokker triplane was achieved by the man most popularly associated with it: Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. Likewise, although Georges Guynemer may not have gained the first aerial victory credited to a Spad 7.C1, he did score the first for the cannon-armed Spad 12.Ca1, in the development of which he had played a prominent role.

Other fighters had combat debuts that were more obscure, and sometimes, as in the case of the Supermarine Spitfire and the Vought F4U-1 Corsair, less than auspicious. Several famous types did not even enter combat with the countries that designed them, for example, the quintessentially French Spad 13.C1 scoring its first victory with a British pilot in the cockpit. Although an American did score the first aerial victory for the North American P-51 Mustang, he did so while serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force!

My original findings were published in Fighting Firsts in Britain in 2001. Since that time, my research for a number of subsequent book projects uncovered an astonishing wealth of new information, adding new factual details. Some revelations include combat debuts that were even earlier and under different circumstances than previously thought. There have even been a few additional fighter types, overlooked in the original book, given their due in this one. Therefore, this volume offers the fruits of more than a dozen years of fresh scholarship. Much of the newly unearthed material represents not only information from some countries from which it was previously not released, but also a proliferation of exchanges with colleagues over the Internet at unprecedented speeds. As with aviation technology, information interchange has undergone some advances in the past few decades that have radically altered the state of the art.