First published in Great Britain in 2005 by

Pen & Sword Aviation

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Peter Caygill, 2005

9781783409358

The right of Peter Caygill to be identified as Author of this Work has

been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Palatino by

Phoenix Typesetting, Auldgirth, Dumfriesshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

W hen the aeroplane first went to war in 1914, it did so without any clear duties, other than endowing the ability to see over the nearest hill. Performance was also marginal due to the heavy, under-powered and often temperamental engines of the day. By the end of the First World War, however, it had become one of the dominant weapons and all its various tactical roles had been clearly defined. In the post-war period the pace of military aircraft development came to a virtual standstill and over the next fifteen years performance levels increased at a relatively modest rate. The RAFs biplane fighters finally made it over 200 mph with the Hawker Fury in June 1931, but the standard bomber of the day, the Vickers Virginia, could only just stagger above 100 mph and had even been known to travel backwards when faced with a stiff headwind.

Improvements in metal aircraft structures, in particular the introduction of stressed skin construction, and the development of more powerful engines for air racing and commercial use, gave the prospect of significantly increased capability, however, it was only the worsening political situation in Europe in the mid 1930s that finally released the Governmental shackles that had been inhibiting the progress of military projects in Britain in particular. The sudden prospect of large orders for fighter aircraft spurred the likes of Sydney Camm at Hawker and Reginald Mitchell at Supermarine to formulate advanced ideas which would eventually become the Hurricane and Spitfire. These aircraft and others, notably the Messerschmitt Bf 109, eclipsed everything that had gone before, offering increases in top speed of around 100 mph, greatly improved rates of climb and much heavier armament.

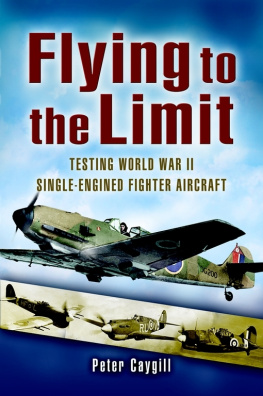

With the coming of the Second World War the impetus was maintained with the development of new engines of up to 2000 hp, all this just a few years after power outputs of a quarter of that amount had been deemed acceptable. Rapid technological advances and the desperate need for large numbers of aircraft put great strain on the various test establishments whose job it was to clear each machine as a weapon of war so that any nineteen-year-old could fly it in reasonable safety. In Britain the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE), together with the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) and the Air Fighting Development Unit (AFDU) were entrusted with this work. This book looks at some of the more notable single-engined fighter aircraft through the performance and handling trials that were carried out by these units, a task that became more and more complex as the conflict went on and as the boundaries were pushed to the absolute limit, in terms of structures, engines and aerodynamics.

Acknowledgments

M uch of my research for this book was carried out at the National Archives at Kew and I would like to thank the staff for their help in tracking down all the official reports and documents that form the basis of this work.

During the course of compiling this book I was very fortunate to be contacted by Len Thorne who spent three years with the Air Fighting Development Unit at Duxford, Wittering and, latterly at Tangmere, by which time it had become the Air Fighting Development Squadron, and was part of Central Fighter Establishment. Prior to his involvement with AFDU Len flew a tour on Spitfires in 1941/42 with 41 Squadron at Catterick/Westhampnett and 602 Squadron at Kenley, during which time he flew alongside the likes of Don Finlay, Al Deere, Paddy Finucane and Victor Beamish.

His logbook makes fascinating reading as he flew virtually every mark of Spitfire up to the F.21. In addition, he flew a wide range of single-engined fighters from the P-51 Mustang, P-47 Thunderbolt and Typhoon/Tempest, to lesser known types such as the Bell Airacobra, Blackburn Skua and Fairey Fulmar. During his time at AFDU he was also entrusted with showing off a captured Focke-Wulf Fw 190A at numerous fighter airfields throughout the country, from Exeter in the south-west to Eshott in Northumberland, and in the course of eighty flights he managed to accumulate over 100 hours on type. My special thanks go to Len for answering my numerous queries on the many aircraft he has flown and for his help and hospitality.

Unless otherwise credited, all the photographs in this book were supplied by Philip Jarrett from his extensive archive and my sincere thanks go to him once again.

Finally, I would like to thank Peter Coles and the production staff at Pen and Sword for their help and assistance with this project.

CHAPTER ONE

Hawker Hurricane

O n 6 November 1935 the prototype Hawker F.36/34 (soon to be named Hurricane) was taken into the air for the first time by Group Captain P.W.S. George Bulman, Hawkers chief test pilot. The type was to form the backbone of Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain, a conflict in which it destroyed more enemy aircraft than all other forms of defence put together. It was to go on to serve with distinction in many other theatres of war and the last Hurricane (PZ865) was delivered in September 1944.

Unlike the more radical Spitfire, the design of the Hurricane was closely related to its immediate forebears and it was initially known as the Fury Monoplane. It was to have been powered by a steam-cooled Rolls-Royce Goshawk, the favoured engine at the time of its inception, but development problems led to the adoption of the new Rolls-Royce PV.12, which later became the Merlin. Initially a fixed, spatted undercarriage and four guns were included in the design, but these quickly gave way to a fully retractable undercarriage and eight guns. The Hurricane followed Hawkers principles of construction, proved during manufacture of the RAFs classic inter-war biplanes fighters, with a standard cross-braced tubular steel structure, which was fabric-covered aft of the cockpit. The cantilever wing was of two-spar construction and was also fabric-covered.

The Hawker F.36/34 (serial number K5083) was passed to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at Martlesham Heath in early 1936 for brief preliminary handling trials. Among the pilots to fly the new fighter was Sergeant (later Group Captain) Sammy Wroath, who was to become a distinguished test pilot and was the first Commandant of the Empire Test Pilots School (ETPS). By the time that K5083 reached Martlesham Heath, it had been modified in several respects and no longer featured the tailplane struts as originally fitted. The sliding canopy had been reinforced with additional frames and the radiator bath had been enlarged to aid cooling. A radio mast had also been fitted and the tail surfaces now had trim tabs.