Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The hand-written journals of the gentlemen adventurers who form the dramatis personae of this book are almost unreadable to the untrained eye. I owe a debt of gratitude to the handful of Victorian scholars long deceased who transcribed these voluminous writings. George Birdwood, Sir William Foster and Henry Stevens made this book possible, as did W. Noel Sainsbury and his indefatigable daughter Ethel who together edited and indexed more than five thousand pages of Jacobean script all done without the aid of computers.

Thank you to Des Alwi on Neira Island for his hospitality, enthusiasm and the use of his twin-engined power boat; to Monsignor Andreas Sol of St Francis Xavier Cathedral in Ambon (Amboyna) for allowing me free access to his extensive library; and to James Lapian at the BBCs Indonesian Service.

In London, I am grateful to Marjolein van der Valk for rendering obscure Dutch chronicles into fluent English; to the staff of the London Library and the British Librarys Oriental and India Office Collections; and to Frank Barrett, Wendy Driver, Maggie Noach and Roland Philipps.

I am particularly indebted to Paul Whyles and Simon Heptinstall, both of whom read numerous versions of the manuscript and suggested much-needed changes.

Finally, I wish to thank my wife Alexandra whose patience, encouragement and cheerfulness will always prove an inspiration.

L IST OF I LLUSTRATIONS

L IST OF M APS

P ROLOGUE

T HE ISLAND CAN BE SMELLED before it can be seen. From more than ten miles out to sea a fragrance hangs in the air, and long before the bowler-hat mountain hoves into view you know you are nearing land.

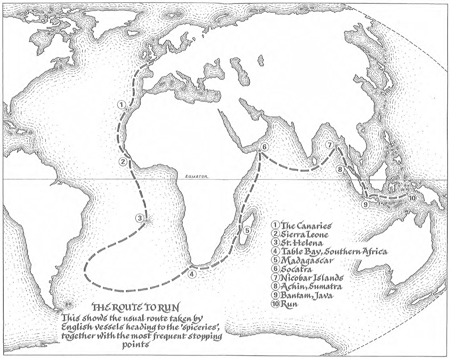

So it was on 23 December 1616. The Swans captain, Nathaniel Courthope, needed neither compass nor astrolabe to know that they had arrived. Reaching for his journal he made a note of the date and alongside scribbled the position of his vessel. He had at last reached Run, one of the smallest and richest of all the islands in the East Indies.

Courthope summoned his crew on deck for a briefing. The stalwart English mariners had been kept in the dark about their destination for it was a mission of the utmost secrecy. They were unaware that King James I himself had ordered this operation, one of such extraordinary importance that failure would bring dire and irrevocable consequences. Nor did they know of the notorious dangers of landing at Run, a volcanic atoll whose harbour was ringed by a sunken reef. Many a vessel had been dashed to splinters on the razor-sharp coral and the shoreline was littered with rusting cannon and broken timbers.

Courthope cared little for such dangers. He was far more worried about the reception he would receive from the native islanders, head-hunters and cannibals, who were feared and mistrusted throughout the East Indies. At your arrival at Run, he had been told, show yourself courteous and affable, for they are a peevish, perverse, diffident and perfidious people and apt to take disgust upon small occasions.

As his men rowed towards land, Courthope descended into his cabin and brushed down his finest doublet, little imagining the momentous events that were to follow. For his discussions with Runs native chieftains conducted in sign language and broken English would change the course of history on the other side of the globe.

* * *

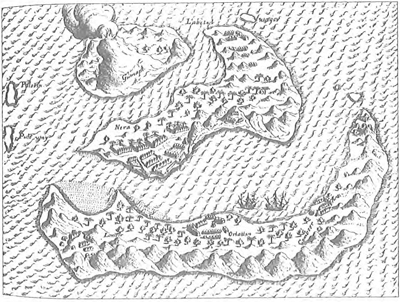

The forgotten island of Run lies in the backwaters of the East Indies, a remote and fractured speck of rock that is separated from its nearest land mass, Australia, by more than six hundred miles of ocean. It is these days a place of such insignificance that it fails even to make it onto the map: The Times Atlas of the World neglects to record its existence and the cartographers of Macmillans Atlas of South East Asia have reduced it to a mere footnote. For all they cared, Run could have slumped beneath the tropical waters of the Indies.

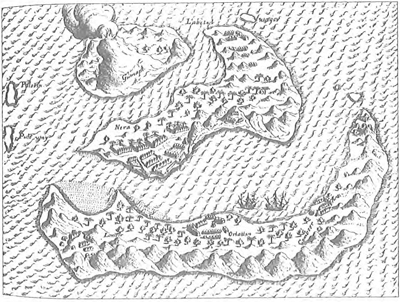

It was not always thus. Turn to the copper-plate maps of the seventeenth century and Run is writ large across the page, its size out of all proportion to its geography. In those days, Run was the most talked about island in the world, a place of such fabulous wealth that Eldorados gilded riches seemed tawdry by comparison. But Runs bounty was not derived from gold nature had bestowed a gift far more precious upon her cliffs. A forest of willowy trees fringed the islands mountainous backbone; trees of exquisite fragrance. Tall and foliaged like a laurel, they were adorned with bell-shaped flowers and bore a fleshy, lemon-yellow fruit. To the botanist, they were called Myristica fragrans. To the plain-speaking merchants of England they were known simply as nutmeg.

Nutmeg, the seed of the tree, was the most coveted luxury in seventeenth-century Europe, a spice held to have such powerful medicinal properties that men would risk their lives to acquire it. Always costly, it rocketed in price when the physicians of Elizabethan London began claiming that their nutmeg pomanders were the only certain cure for the plague, that pestiferous pestilance that started with a sneeze and ended in death. Overnight, this withered little nut until now used to cure flatulence and the common cold became as sought after as gold.

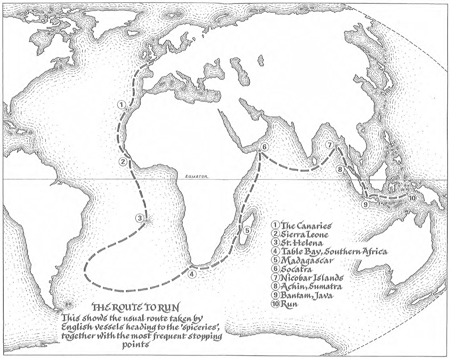

There was one drawback to the sudden and urgent demand: no one could be sure from exactly where the elusive nutmeg originated. Londons merchants had traditionally bought their spices in Venice, and Venices merchants had in turn bought them in Constantinople. But nutmeg came from much further east, from the fabled Indies which lay far beyond Europes myopic horizons. Ships had never before plied the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean and maps of the far side of the globe remained a blank. The East, as far as the spice dealers were concerned, could have been the moon.

Had they known in advance of the difficulties of reaching the source of nutmeg they might never have set sail. Even in the East Indies where spices grew like weeds, nutmeg was a rarity; a tree so fussy about climate and soil that it would grow only on a tiny cluster of islands, the Banda archipelago, which were of such impossible remoteness that no one in Europe could be sure if they existed at all. The spice merchants of Constantinople had scant information about these islands and what they did know was scarcely encouraging. There were rumours of a monster that preyed on passing ships, a creature of devillish possession that lurked in hidden reefs. There were stories of cannibals and head-hunters bloodthirsty savages who lived in palm-tree shacks decorated with rotting human heads. There were crocodiles that lay concealed in rivers, hidden shoals to catch captains unawares, and such mightie stormes and extreme gusts of winde that even the sturdiest of ships were placed in grave risk.