A. B. Guthrie Jr. - The Big Sky

Here you can read online A. B. Guthrie Jr. - The Big Sky full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2002, publisher: Mariner Books, genre: Adventure. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Big Sky

- Author:

- Publisher:Mariner Books

- Genre:

- Year:2002

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Big Sky: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Big Sky" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A. B. Guthrie Jr.: author's other books

Who wrote The Big Sky? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Big Sky — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Big Sky" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Big Sky

A B Guthrie Jr

1952

To My Father

Contents

Foreword

by Wallace Stegner

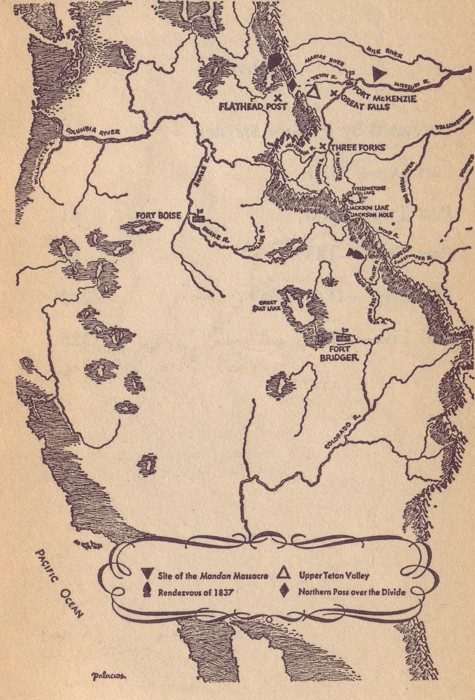

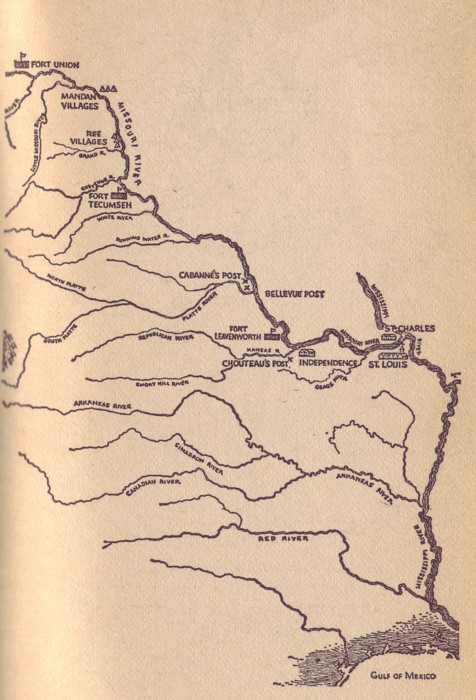

A. B. Guthrie's The Big Sky does not belie its title. It is a novel lived entirely in the open. The big wild places are both its setting and its theme, and everything about the book is as big as the country it moves in. The story sweeps westward from Kentucky to St. Louis and up the interminable Missouri through Omaha and Pawnee country, past Ree and Sioux country, into Stoney and Big Belly and Blackfoot country, and there, riding on the boil of its own excitement, it waits out its climax. Bigness, distance, wildness, freedom, are the dream that pulls Boone Caudill westward into the mountains, and the dream has an incandescence in the novel because it is also the dream that Bud Guthrie grew up on.

The country he takes us through with Caudill, Jim Deakins, and Dick Summers is his native landscape, known since childhood. It is a sign of commitment, an evidence of love, that when he gives wildness its fleeting consummation by settling Boone Caudill in a Blackfoot lodge with the girl Teal Eye, he locates that idyllic camp on the river called variously the Tansy, Breast, Teton, or Titty -essentially the valley around Choteau, Montana, where Guthrie lived as a boy and has settled as a man. It is country of a kind I know well -at the edge of the mountains but not in them: high plains country, chinook country, its air like a blade or a blowtorch, its sky fitting down close and tight to the horizons and the great bell of heaven alive with light, clouds, heat, stars, winds, incomparable weathers. But even if I had never been within a thousand miles of Montana I could not miss Guthrie's love and knowledge of the land he writes about, and I could not avoid knowing something of what that unmarked wilderness would have meant to a Boone Caudill. The big plains and the surging ranges and the hidden valleys are a fit setting for his story of intractable liberty and violence; and in the end they turn out to be not only a setting and a theme, but also, like Caudill himself, victim. The West of The Big Sky is Innocence, anti-civilization, savage and beautiful and doomed, a dream that most Americans, however briefly or vainly, have dreamed, and that some have briefly captured.

Serious writers about the West have often had to celebrate scenery for lack of the social complexities out of which most fiction is made. Geography, at least, is one matter in which a Westerner can excel and in which he takes pride. History is another. For in a region only three generations from the total wildness of buffalo and horse Indians, everything, including history, must be built from scratch. Like any other part of a human tradition, history is an artifact. It does not exist until it is remembered and written down; and it is not truly remembered or written down until it has been vividly imagined. We become our past, and it becomes a part of us, by our reliving of our beginnings. Guthrie's three novels, which form a loose trilogy, have as one of their justifications the creation of such a usable human memory. It is most closely focused on Guthrie's home country, but it has validity for the entire West.

These are novels, works of the imagination, and yet it is not improper to think of them as related to the trilogy of great histories that constitute the major work of Guthrie's friend Bernard DeVoto. DeVoto touched history with a novelist's imagination; Guthrie imagines his novels around a historian's sure knowledge. These two, each after his own impressions, together took the long journey up the Missouri in the wake of the fur hunters' keelboats, and their imaginative reconstructions cover much common ground. The Big Sky, a story of mountain men, pairs off naturally with Across the Wide Missouri; The Way West chronicling the trail to Oregon, goes in team with The Year of Decision, 1846. But that is as far as the parallelism extends. DeVoto goes backward, gathering up all the history of western exploration in The Course of Empire, while Guthrie goes onward in time to deal, in These Thousand Hills, with the Montana cattle empire of the 1880's.

Nevertheless both the man from Utah and the man from Montana share a characteristic western impulse: they are intent on creating a past, firming up a ground on which the present can stand and by which it can be comprehended. And both make whatever use can be made of those slight, accidental linkages by which discrete happenings become historical continuity. Thus Guthrie, completely in accordance with historical probability, returns Dick Summers to the wild country of his youth as guide to an Oregon train in The Way West; and again in accordance with probability, has Lat Evans, son of Brownie and Mercy Evans of The Way West, trail a herd of Durham cattle eastward from Oregon into Montana in These Thousand Hills. And when Lat Evans stakes out his own ranch after a career of wolfing and bronc busting, he stakes it out on that same Tansy, Breast, Teton, or Titty River where Boone Caudill had lived his idyll with Teal Eye and the Piegans of Heavy Runner's band -and where twenty years later a boy named Bud Guthrie, son of the editor of the Choteau Acantha, would be hanging out his ears listening to cowpunchers, sheepherders, drifters, politicians, and wandering journalists talking of a past that no one yet had begun to write down.

The Big Sky is the first, and for me the best, of the three novels that eventually came of that listening. What makes it special is not merely its narrative and scenic vividness, but the ways in which Boone Caudill exemplifies and modifies an enduring American type.

Caudill is an avatar of the oldest of all the American myths -the civilized man recreated in savagery, rebaptized into innocence on a wilderness continent. His fabulous ancestors are Daniel Boone, who gives him his name, and Cooper's Leatherstocking; and up and down the range of American fiction he has ten thousand recognizable siblings. But Caudill has his own distinction, for he is neither intellectualized nor sentimentalized. He may be White Indian, but he is no Noble Savage -for the latter role he is not noble enough, and far too savage. Though he retains many mythic qualities -the preternatural strength and cunning, the need for wild freedom, the larger-than-life combination of Indian skills and white mind- he has no trace of Leatherstocking's deist piety. His virtues are stringently limited to the qualities of self-reliance, courage, and ruthlessness that will help him to survive a life in which few died old. Guthrie clearly admires him, but with reservations enforced by the hindsights of history. Boone Caudill's savagery, admirable and even enviable though it is, can lead nowhere. The moral of his lapse from civilization is that such an absolute lapse is doomed and sterile, and in the end the savagery which has been his strength is revealed as his fatal weakness.

For Boone's course leaves him nowhere to go. By midnovel, having fled the settlements and the settlements' law and the authority of a harsh father, he has cut himself off so utterly that he can hardly stand the civilization of so remote an outpost as Fort Union, on the Yellowstone. He elects the wild, he symbolically marries the wilderness when he brings Teal Eye into his tepee on the Teton. But that too, the one thing he wants, the one thing he is fit for, will be his only a little while. He is a killing machine, as dangerous to what he loves as to what he hates, and what the logic of his ferocious adaptation demands, the novel's action fulfills. In the same moment when he shoots Jim Deakins, the one friend who has bound him to the past and to civilization, he breaks his bond with Teal Eye and the Blackfeet; and the son who might have represented continuity and a compromise between the two ways of life has been -how properly for both the historical rightness and the fictional inevitability of his theme!- born blind.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Big Sky»

Look at similar books to The Big Sky. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Big Sky and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.