Translated from the Danish by Charlotte Barslund with Emma Ryder

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT

Boston New York

2010

Copyright 2006 by Carsten Jensen og Gyldendal

Translation copyright 2010 by Charlotte Barslund

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jensen, Carsten, date.

[Vi, de druknede. English]

We, the drowned / Carsten Jensen ; translated from the Danish

by Charlotte Barslund with Emma Ryder.

p. cm.

"Translation of: Vi, de druknede"T.p. verso.

ISBN 978-0-15-101377-7

I. Barslund, Charlotte. II. Ryder, Emma. III. Title.

PT 8176.2. E 44 V 513 2010

839.8'1374dc22 2009046568

Translation of Vi, de druknede

This translation has been sponsored by

the Danish Arts Council Committee for Literature.

Book design by Lisa Diercks

Text set in FF Clifford

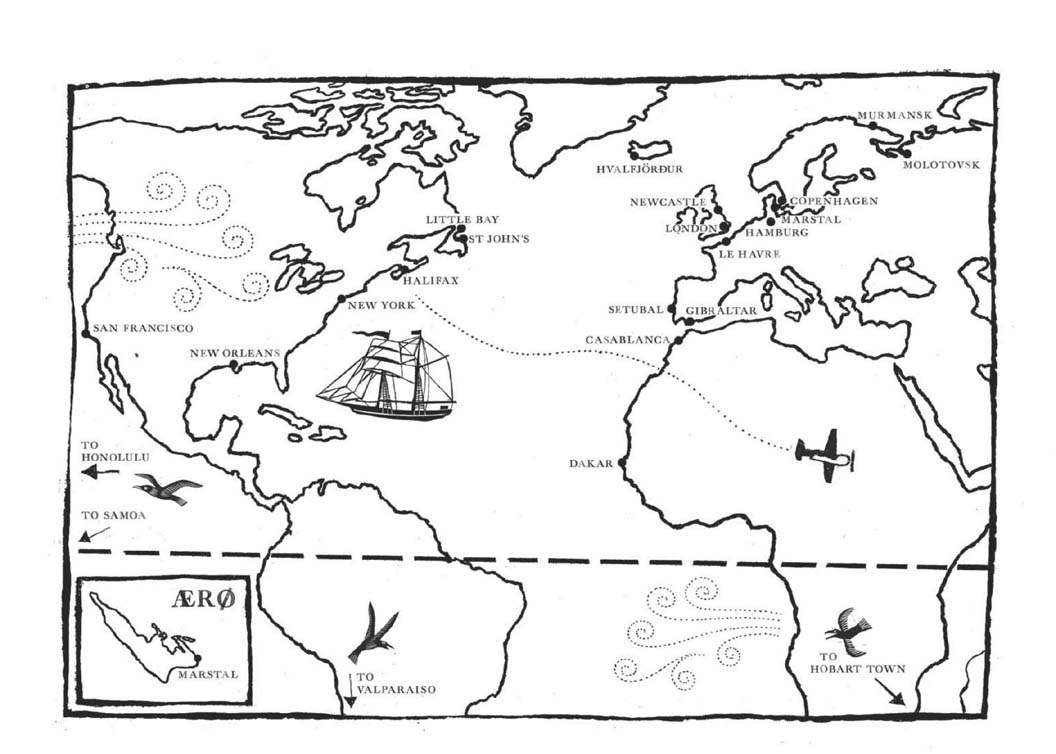

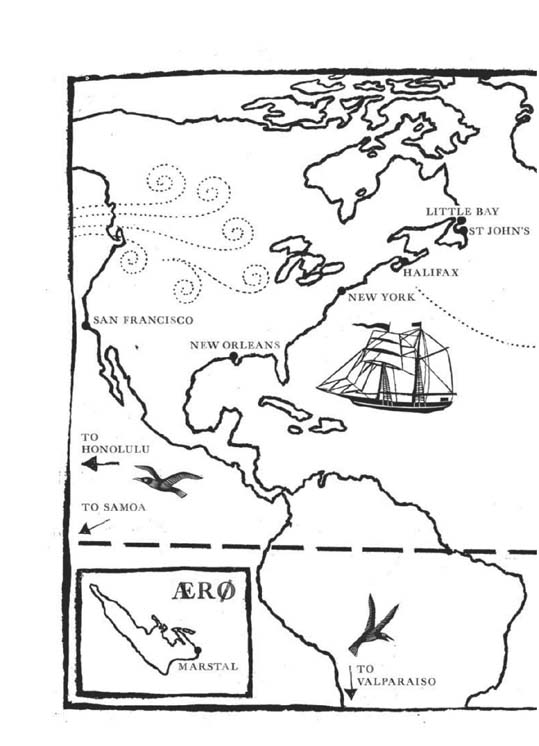

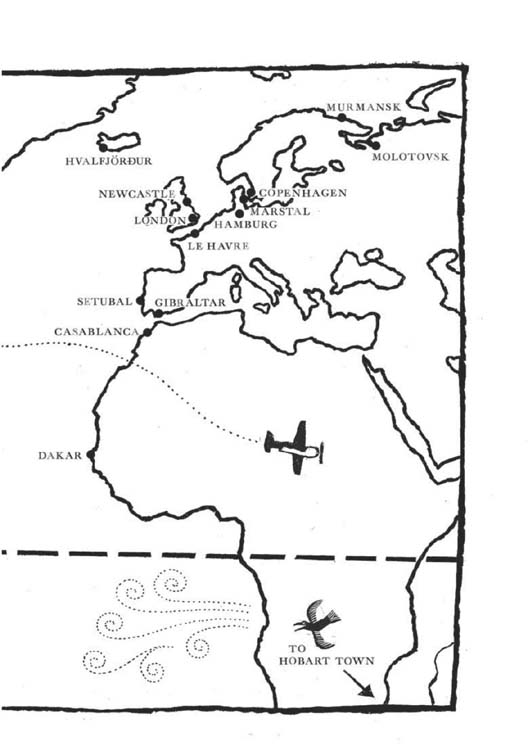

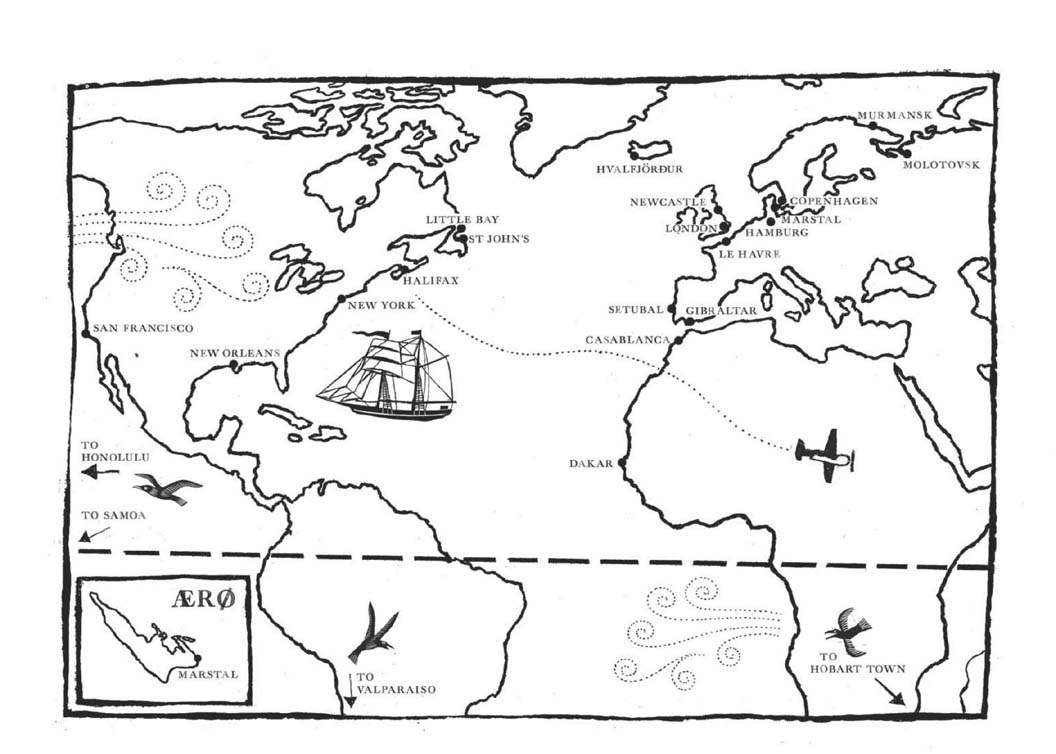

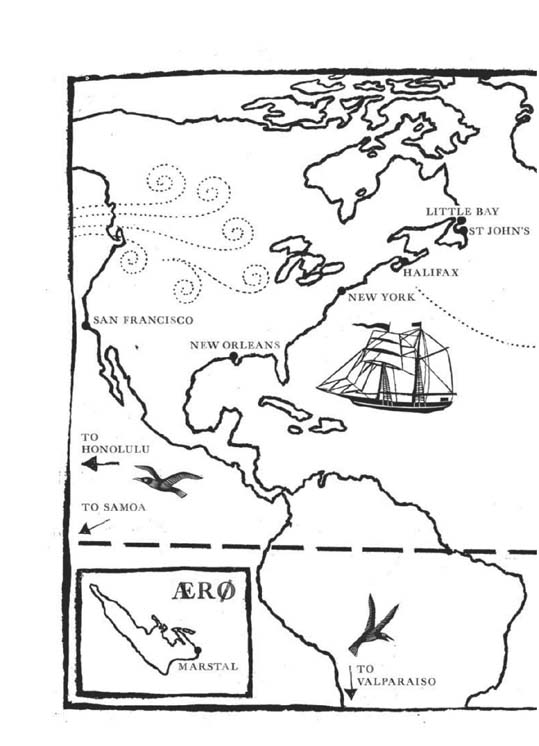

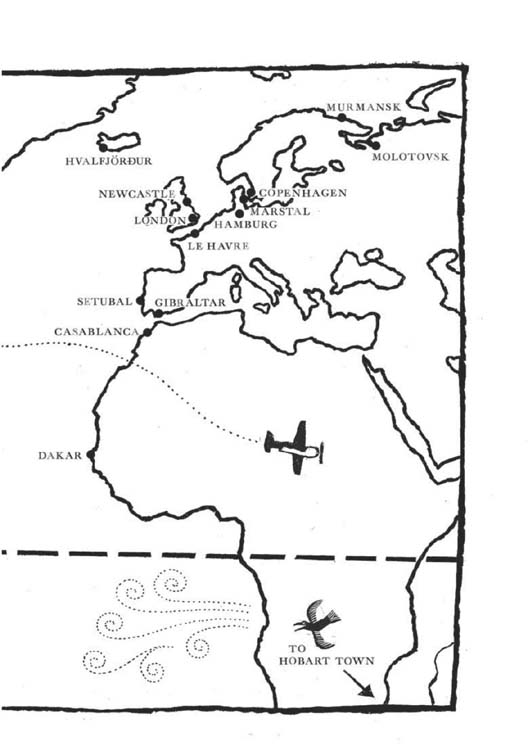

Map by Joe McClaren

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The author is grateful for financial assistance from the following:

Statens Kunstfond

Litteraturrdet

Autorkontoen

Statens Kunstrds Litteraturudvalg

Politikens Fond

J. C. Hempels Fond

Konsul Georg Jorck og hustru Emma Jorcks Fond

Fonden Erik Hoffmeyers Rejselegat

For Lizzie, the love of my life

CONTENTS

I

The Boots

The Thrashing Rope

Justice

The Voyage

The Disaster

II

The Breakwater

Visions

The Boy

North Star

III

The Widows

The Seagull Killer

The Sailor

Homecoming

IV

The End of the World

Acknowledgments

I

THE BOOTS

M ANY YEARS AGO there lived a man called Laurids Madsen, who went up to Heaven and came down again, thanks to his boots.

He didn't soar as high as the tip of the mast on a full-rigged ship; in fact he got no farther than the main. Once up there, he stood outside the pearly gates and saw Saint Peterthough the guardian of the gateway to the Hereafter merely flashed his bare ass at him.

Laurids Madsen should have been dead. But death didn't want him, and he came back down a changed man.

Until the fame he achieved from this heavenly visit, Laurids Madsen was best known for having single-handedly started a war. His father, Rasmus, had been lost at sea when Laurids was six years old. When he turned fourteen he shipped aboard the Anna of Marstal, his native town on the island of r, but the ship was lost in the Baltic only three months later. The crew was rescued by an American brig and from then on Laurids Madsen dreamt of America.

He'd passed his navigation exam in Flensburg when he was eighteen and the same year he was shipwrecked again, this time off the coast of Norway near Mandal, where he stood on a rock with the waves slapping on a cold October night, scanning the horizon for salvation. For the next five years he sailed the seven seas. He went south around Cape Horn and heard penguins scream in the pitch-black night. He saw Valparaiso, the west coast of America, and Sydney, where the kangaroos hop and the trees shed bark in winter and not their leaves. He met a girl with eyes like grapes by the name of Sally Brown, and could tell stories about Foretop Street, La Boca, Barbary Coast, and Tiger Bay. He boasted about his first equator crossing, when he'd saluted Neptune and felt the bump as the ship passed the line: his fellow sailors had marked the occasion by forcing him to drink salt water, fish oil, and vinegar; they'd baptized him in tar, lamp soot, and glue; shaved him with a rusty razor with dents in its blade; and tended to his cuts with stinging salt and lime. They made him kiss the ocher-colored cheek of the pockmarked Amphitrite and forced his nose down her bottle of smelling salts, which they'd filled with nail clippings.

Laurids Madsen had seen the world.

So had many others. But he was the only one to return to Marstal with the peculiar notion that everything there was too small, and to prove his point, he frequently spoke in a foreign tongue he called American, which he'd learned when he sailed with the naval frigate Neversink for a year.

"Givin nem belong mi Laurids Madsen," he said.

He had three sons and a daughter with Karoline Grube from Nygade: Rasmus, named after his grandfather, and Esben and Albert. The girl's name was Else and she was the oldest. Rasmus, Esben, and Else took after their mother, who was short and taciturn, while Albert resembled his father: at the age of four he was already as tall as Esben, who was three years his senior. His favorite pastime was rolling around an English cast-iron cannonball, which was far too heavy for him to liftnot that it stopped him from trying. Stubborn-faced, he'd brace his knees and strain.

"Heave away, my jolly boys! Heave away, my bullies!" Laurids shouted in encouragement, as he watched his youngest son struggling with it.

The cannonball had come crashing through the roof of their house in Korsgade during the English siege of Marstal in 1808, and it had put Laurids's mother in such a fright that she promptly gave birth to him right in the middle of the kitchen floor. When little Albert wasn't busy with the cannonball it lived in the kitchen, where Karoline used it as a mortar for crushing mustard seeds.

"It could have been you announcing your arrival, my boy," Laurids's father had once said to him, "seeing how big you were when you were born. If the stork had dropped you, you would have gone through the roof like an English cannonball."

"Finggu," Laurids said, holding up his finger.

He wanted to teach the children the American language.

Fut meant foot. He pointed to his boot. Maus was mouth.

He rubbed his belly when they sat down to eat. He bared his teeth.

"Hanggre."

They all understood he was telling them he was hungry.

Ma was misis, Pa papa tru. When Laurids was absent, they said "Mother" and "Father" like normal children, except for Albert. He had a special bond with his father.

The children had many names, pickaninnies, bullies, and hearties.

"Laihim tumas," Laurids said to Karoline, and pursed his lips as if he was about to kiss her.

She blushed and laughed, and then got angry.

"Don't be such a fool, Laurids," she said.

I N 1848, WAR BROKE OUT between the Danish crown and the rebellious Germans across the Baltic in Schleswig-Holstein, who wanted to cut their ties with Denmark. The old customs steward, de la Porte, was the first to know because the provisional insurgent government in Kiel sent him a "proclamation," accompanied by a request to hand over the customs coffers.

All of r was up in arms, and we immediately formed a home guard led by a young teacher from Rise, who from then on was known as the General. On the highest points of the island we erected beacons made of barrels filled with tar and old rope, attached to poles. If the German came by sea, we'd signal his approach by setting them alight and hoisting them up.

Next page