THE KARLUKS LAST VOYAGE CHAPTER I THE EXPEDITION AND ITS OBJECTS

We did not all come back.

Fifteen months after the Karluk, flagship of Vilhjalmar Stefanssons Canadian Arctic Expedition, steamed out of the navy yard at Esquimault, British Columbia, the United States revenue cutter, Bear, that perennial Good Samaritan of the Arctic, which thirty years before had been one of the ships to rescue the survivors of the Greely Expedition from Cape Sabine, brought nine of us back again to Esquimaultnine white men out of the twenty, who, with two Eskimo men, an Eskimo woman and her two little girlsand a black catcomprised the ships company when she began her westward drift along the northern coast of Alaska on the twenty-third of September, 1913. Years of sealing in the waters about Newfoundland and of Arctic voyaging and ice-travel with Peary had given me a variety of experience to fall back upon by way of comparison; the events of those fifteen months, I must say, justified the prophecy that I made in a letter to a Boston friend, just before we left Esquimault: This will have the North Pole trip beaten to a frazzle.

It did; and there were two main reasons why.

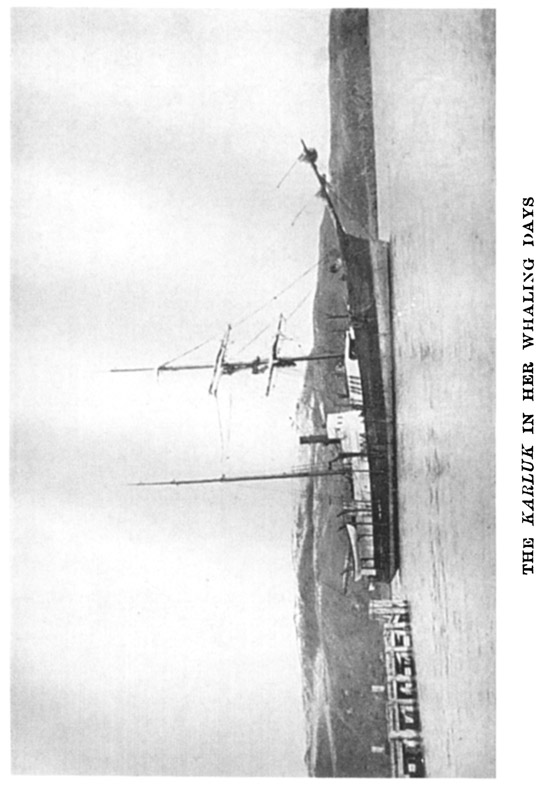

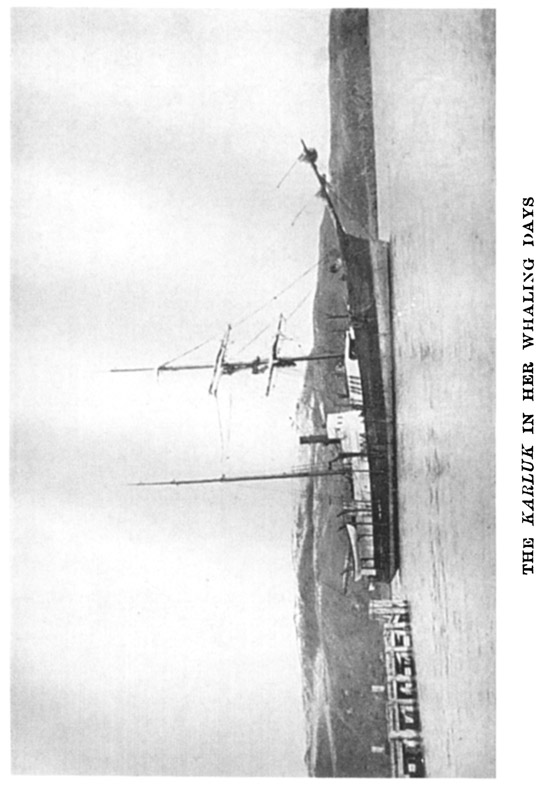

One was that the Karluk, though an old-time whaler, was not built, as the Roosevelt was, especially for withstanding ice-pressure; very few ships are. Dr. Nansens ship, the Fram, was built for the purpose and has had a glorious record in both the Arctic and the Antarctic. The Karluk, a brigantine of 247 tons, 126 feet long, 23 feet in beam, drawing 16 feet when loaded, was built in Oregon originally to be a tender for the salmon-fisheries of the Aleutian Islands. Her duty had been to go around among the stations and pick up fish for the larger ships. The word karluk, in fact, is Aleut for fish. When later in her career she was put into the whaling service her bow and sides were sheathed with two-inch Australian ironwood but she had neither the strength to sustain ice-pressure nor the engine-power to force her way through loose ice. She had had, however, an honorable career in the now virtually departed industry of Arctic whaling, and was personally and pleasantly known to Stefansson, who had travelled on her from place to place along the Alaskan coast on several occasions during his expeditions of 19067 and 190812.

The other reason was that the winter of 191314 was unprecedented in the annals of northern Alaska. It came on unusually early, as we were presently to learn, and for severity of storm and cold had not its equal on record.

The National Geographic Society had originally planned to finance our expedition, and it was only at the urgent request of the Canadian premier, the Right Hon. R. L. Borden, that the Society relinquished its direction of the enterprise. The Canadian Government felt that since the country to be explored was Canadian territory it was only fitting that the expedition fly its flag and be financed from its treasury.

When I returned from the seal-fisheries to Brigus, my old home in Newfoundland, in the spring of 1913, I found awaiting me a telegram from Stefansson, asking me to join his expedition and take charge of the Karluk. I went at once to New York, then to Ottawa for a day with the government authorities and direct from there to Victoria, B. C. It was the middle of May and there was work to be done to get the ship ready to sail in June.

It was an elaborate expedition, one of the largest and most completely equipped, I believe, that have ever gone into the Arctic. It differed, too, in one other respect than that of size, from previous Arctic expeditions, in that its main objects were essentially practical,in fact, one might say, commercial. It was in two divisions. The northern party, under Stefansson himself, was primarily to investigate the theory so ably advanced by Dr. R. A. Harris of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey that new landperhaps a new continentwas to be found north of Beaufort Sea, which is that part of the Arctic Ocean immediately to the north of Alaska. The main work of the party aboard the Karlukto quote Stefanssonwas to be the exploration of the region lying west of the Parry Islands and especially that portion lying west and northwest from Prince Patrick Island. The Karluk was to sail north approximately along the 141st meridian until her progress was interfered with either by ice or by the discovery of land. If land were discovered a base was to be established upon it, but if the obstruction turned out to be ice an effort was to be made to follow the edge eastward with the view of making a base for the first years work near the southwest corner of Prince Patrick Island, or, failing that, on the west coast of Banks Island. The Karluk was to go first to Herschel Island, the old rendezvous of the Arctic whaling fleet and the northernmost station of the Canadian Mounted Police. If she should be beset in the ice and forced to drift, it was expected that certain theories about the direction of Arctic currents would be tested, and there would also be opportunity for dredging and sounding.

Both of these main objects were accomplished: Stefansson ultimately found new land and the Karluk engaged in an Arctic drift, but neither result was attained in quite the way which was planned when we were getting the ship ready in May and June, 1913. We returnedsome of usrather earlier than we had expected, for we were prepared to be away until September, 1916, and contrary to one of the theories of Arctic currents we did not drift across the Pole to the Greenland shore. Before we started some of the newspaper accounts of the expedition said that the ship might be crushed in the ice; the newspapers are more often correct than they are supposed to be.

Travelling to Herschel Island on the Mary Sachs and the. Alaska, small schooners equipped with gasolene engines, the southern party, under Dr. R. M. Anderson, who had been Stefanssons only white companion on his previous expeditions, was to map the islands already discovered east of the mouth of the Mackenzie River; to make a collection of the Arctic flora and fauna; to survey the channels among the islands, in the hope of establishing trade-routes; to make a geological survey of the coast from Cape Parry to Kent Peninsula and of Victoria Island north and east of Prince Albert Sound, with the primary object of investigating copper-bearing formations; and to study still further the blond Eskimo who had been discovered by Stefansson in 1910.

Pearys attainment of the North Pole in 1909, the goal of three centuries of struggle, enabled the world to give attention to problems unrelated to polar discovery and afforded men an opportunity to realize not only that a million square miles in the Arctic still remained marked on the maps as unexplored territory, but also that a great deal remained to be done in regions which already had technically been discovered. Stefansson himself had already proved this. The shores of Dolphin and Union Straits, for instance, had been mapped by Dr. John Richardson as far back as 1826, yet Stefansson, when he found the blond Eskimo there in 1910, was the first white man on record who had ever visited that tribe in all its history. After his return from that remarkable expedition, I had made his acquaintance at a dinner in New York, some time previous to the planning of the expedition of 191316, and admired him for his scientific achievements and for his skill and daring in living so long off the country in his many months of exploration in the territory east of the Mackenzie River.

The scientific staff gathered for the expedition was large and well-equipped. Besides Stefansson, anthropologist, and Dr. Anderson, zoologist, it included twelve men who were all specialists. The Canadian Geological Survey detailed four men to our party: George Malloch, an expert on coal deposits and stratiography, who had been a graduate student at Yale; J. J. ONeill, a mining geologist, whose specialty was copper; and Kenneth Chipman and J. R. Cox, skillful topographers. For studying ocean currents and tides and the treasures that might be brought up from the bottom of the sea we had James Murray of Glasgow, oceanographer, who had worked for many years with the late Sir John Murray, one of the worlds greatest authorities on the ocean. Murray had been with Sir Ernest Shackleton on his Antartic expedition and afterwards had been biologist of the boundary survey of Colombia, South America. To study the fish of the Arctic Ocean we had Fritz Johansen, who had been marine zoologist with Mylius Erichsen in East Greenland and had done scientific work for the Department of Agriculture at Washington. As forester we had Bjrne Mamen, from Christiania, Norway, who had been on a trip to Spitsbergen and had done work in the timber-lands of British Columbia. As the study of the Eskimo was one of the most interesting objects of the expeditions we quite naturally had two anthropologists besides Stefansson, one, Dr. Henri Beuchat of Paris, the other, Dr. D. Jenness, an Oxford Rhodes Scholar, from New Zealand. The magnetician was William Laird McKinlay, a graduate of the University of Glasgow, who had been studying in the Canadian Meteorological Observatory in Toronto. The photographer was George H. Wilkins, a New Zealander, who had been a photographer in the Balkan War and possessed mechanical ability. He had a motion-picture apparatus as well as other cameras. In medical charge of the expedition was Dr. Alister Forbes Mackay, who had served in the British navy after his graduation from the University of Edinburgh, and, like Murray, had accompanied Shackleton into the Antarctic. Five of these twelve men, as shall be related, were to lay down their lives in the cause of science during the coming year.