Contents

Copyright 2017 by Kenn Harper

All Rights Reserved

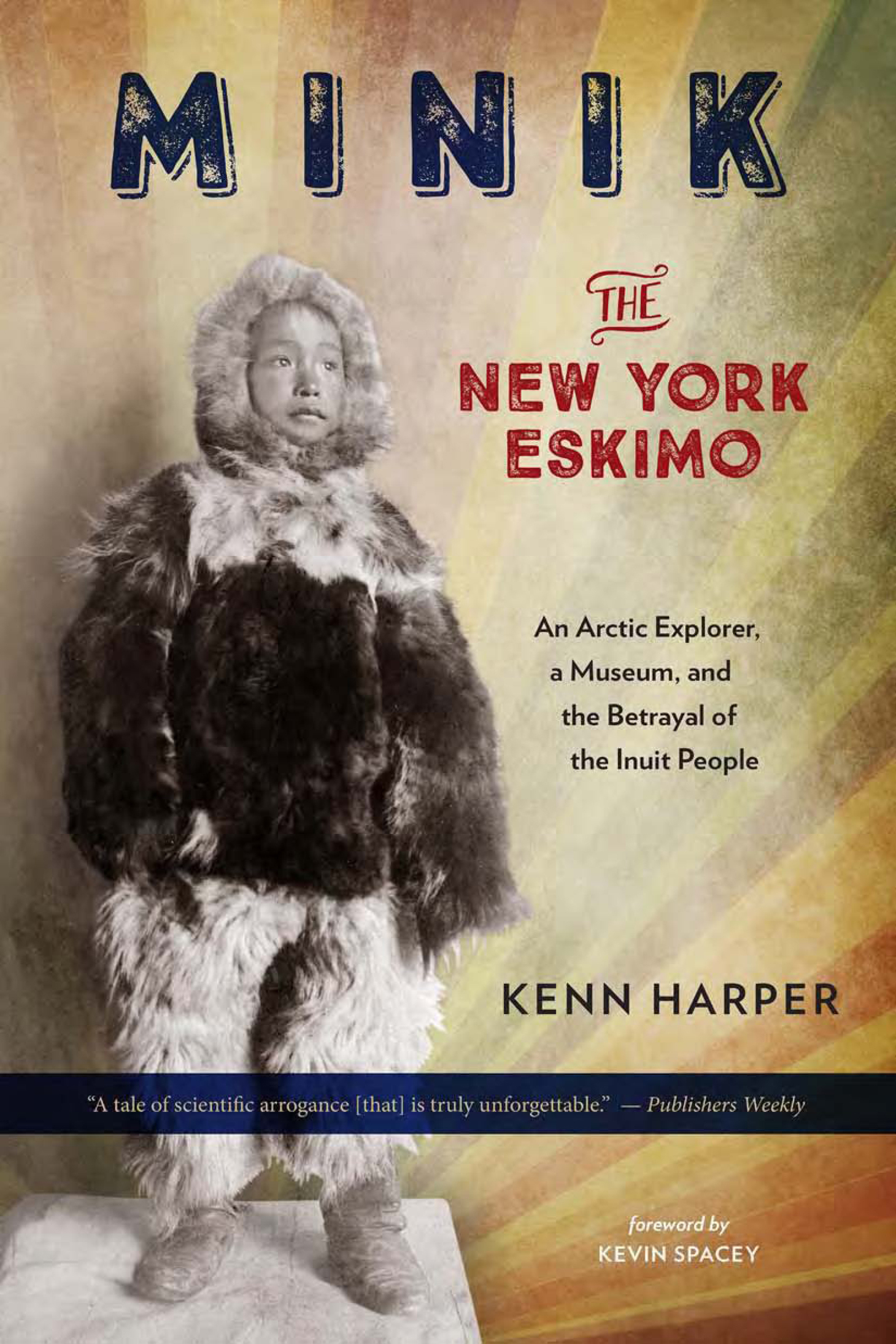

This is a greatly revised and updated version of an earlier work published as Give Me My Fathers Body: The Life of Minik, the New York Eskimo

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to:

Steerforth Press, L.L.C., 45 Lyme Road, Suite 208

Hanover, NH 03755

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN9781586422417

Ebook ISBN9781586422424

First Edition

v4.1

a

To many a good person the thought at once arises: Poor things [the Polar Eskimos]why wouldnt it be a good plan to take them away from their awful home to a pleasanter region?I answer at once, God willing, never.

R OBERT P EARY , Arctic explorer

Our tales are narratives of human experience, and therefore they do not always tell of beautiful things. But one cannot both embellish a tale to please the hearer and at the same time keep to the truth. The tongue should be the echo of that which must be told, and it cannot be adapted according to the moods and the tastes of man.

O SARQAQ , a Polar Inuk

This Minik seems gradually to have become a legendary figure to the Polar Eskimos who have many anecdotes to tell of him and his doings.

E RIK H OLTVED , ethnologist

To my daughters, Aviaq and Mikisoq

And in memory of their brother, my son,

Mamarut

May 25, 1975August 6, 1995

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

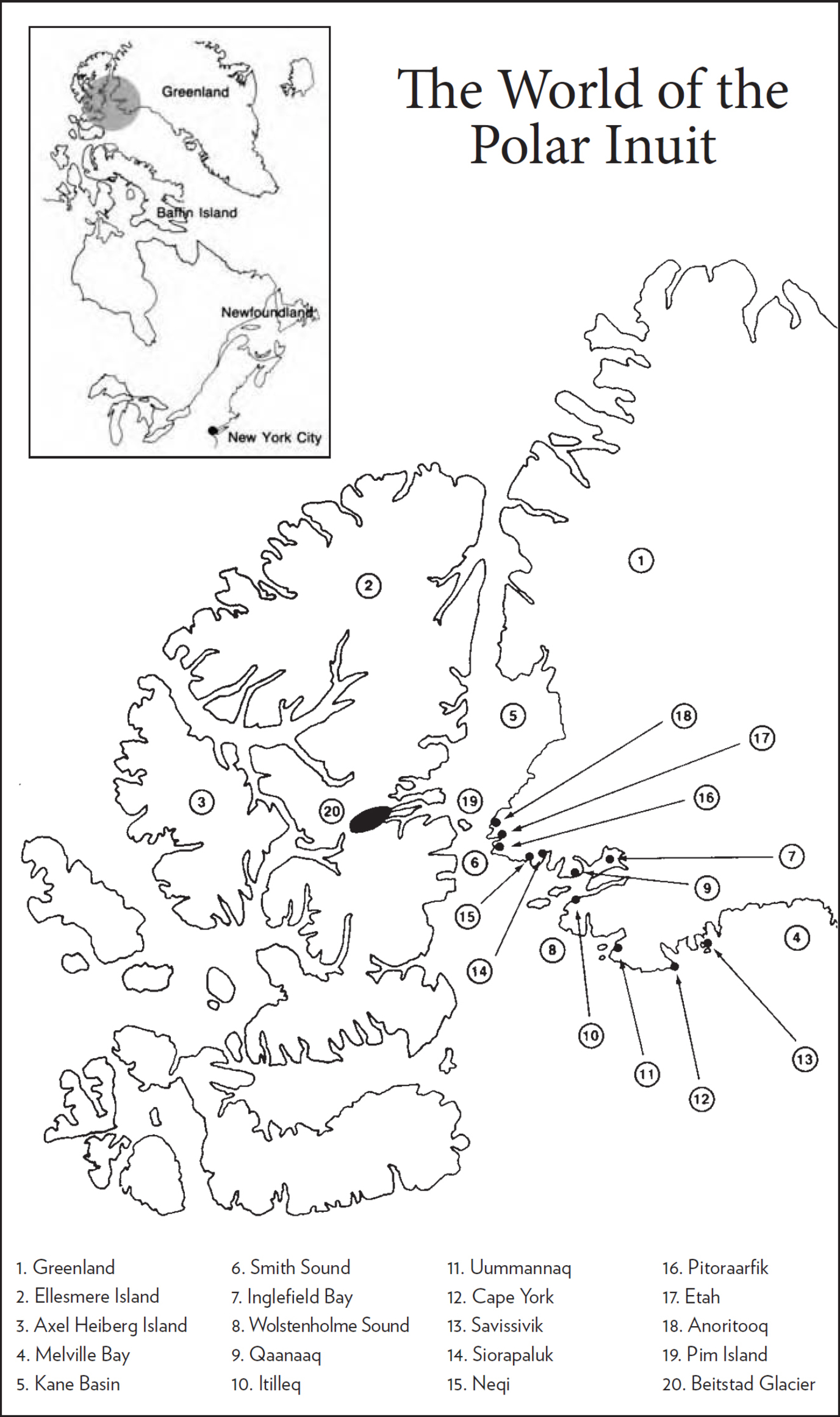

A nybody who makes his living in the acting business is always on the prowl for a good story, and a few years ago, in Canada, I stumbled across a great one. An article in a Toronto paper outlined the life of Minik Wallace, the youngest of a group of Polar Inuit brought to New York City in 1897 by the famed Arctic explorer Robert Peary. Four of the group, including Miniks father, soon died, and in time Minik himself was gradually set adrift by officials of the American Museum of Natural History, whose Department of Anthropology apparently had encouraged Peary to bring them an Inuk specimen to study; by Peary, who was preoccupied with his efforts to reach the North Pole; and by William Wallace, who took in Minik and gave him a name but whose life was eventually swallowed up by financial troubles and personal tragedy. Within a few years of his arrival in New York, Minik had forgotten his native language, his education had come to a halt, his health was shaken by recurrent bouts of pneumonia, and he was left, without family, to fend for himself.

When I managed to find a copy of the book originally published by the author, Kenn Harper, and sold mainly from a general store on Baffin Island in what is now the new Arctic territory of NunavutI found a story that grabbed hold of me and wouldnt let go. In Give Me My Fathers Body [now revised and republished as Minik: The New York Eskimo] the saga of Arctic exploration is told for the first time through the eyes of Inuit, whose rugged endurance and knowledge of the Arctic were largely what made Pearys epic journeys possible in the first place. The wealth and power of New York City on the cusp of the twentieth century of course dazzled the child newly arrived from the worlds northernmost human community. But Americas excited curiosity over the Inuit quickly faded, and Minik soon encountered another side of Americaone of pride and arrogance, and of a cold indifference that seemed to be explained by the boys dark skin.

The reader watches this tale unfold much as Minik didslowly, through small events and casual remarks. The world-famous Peary, a kind of demigod when hes first introduced, is gradually revealed to be a careless, self-absorbed man, who for years refused to return Minik to his home in Greenland. The scientists who studied Minik and put the skeleton of the boys father on display were subject to crackpot theories of racial difference. Their refusal to return the body or even give a reason why it was kept at the museum helps to explain the recent passage of laws compelling museums and other cultural institutions to return to native communities sacred objects and human remains long treated as museum property.

But shining at the heart of this often dark tale, told with such care and restraint, is the spirit of Minik himselfcut off from his people, his language, and his sense of belonging in the world, he never surrendered his hope of going home, his demand for the return of his fathers body for a proper burial, or his belief that people would understand and come to his aid if only he succeeded in explaining himself. Eventually as a young man in his teens, Minik finally shamed a group of Pearys backers into providing him with passage back to Greenland.

Once there he relearned his native language, became a skilled hunter, and hired himself out as a guide and interpreter to later explorers, but Minik found himself caught between two worlds. He longed to speak English, could communicate some of what he felt only to white men, and found that a part of him preferred the bright lights of Broadway to the northern lights. Inevitably, Minik began to dream of another trip homethis time back to New York City.

And there you have itMinik had no home. Plucked from his own world, never wholly welcomed by another, he was condemned to look forever for what he had lost. The entire story is captured in the gaze of the child Minik in one of the photographs in this booka small boy in spiffy cap and coat, holding a bicycle too big for him, looking directly into the heart and soul of whoevers behind the camera for something warmer than curiosity.

This too short, too sad life, unfolding at the end of the great age of Arctic exploration, was pieced together in an amazing effort of research and writing by Kenn Harper, who lived for fifty years among Inuit (as the descendants of historys Eskimos prefer to be called today). Unlike most white men in todays Arctic, he speaks Inuktitut, the language of the Inuit, and heard of Minik firsthand from Greenland Inuit in the mid-1970s. The tale had a mythic qualitythe boy swept off to a magical land where fantastic adventures awaited him and a benefactor promised great wealth; his sudden return years later. But after Minik left Greenland the second time the Polar Inuit heard no more; none could tell Harper what happened to him, where he died or when. There was no end to his tale. Over a period of eight years Harper searched out the answers for himself in Greenland, in New York City, and in Denmark.

The story of Minik has the simplicity and resonance of myth. But Harpers telling of it sketches in a whole age and world, bringing to life the bustling city of New York, the infant science of anthropology, Americas astonished discovery of the Polar Inuit, the American racism that treated people of color as specimens, the huckstering public entertainers who added Inuit and other exotic peoples to their menageriethere is not a page in this book without its horrors and its wonders.

When you get to the end of a great story there comes a moment of silence. The lights in the theater come up, or you turn the last page in a book as good as this one, and you sit stunned. There is nothing to say. And then in the next heartbeat you think of a million things to say.