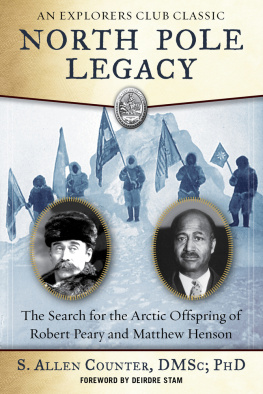

Copyright 1991, 2018 by S. Allen Counter

Foreword Copyright 2018 by Deirdre Stam

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

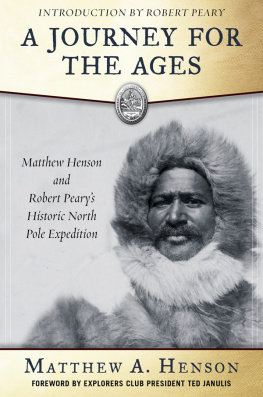

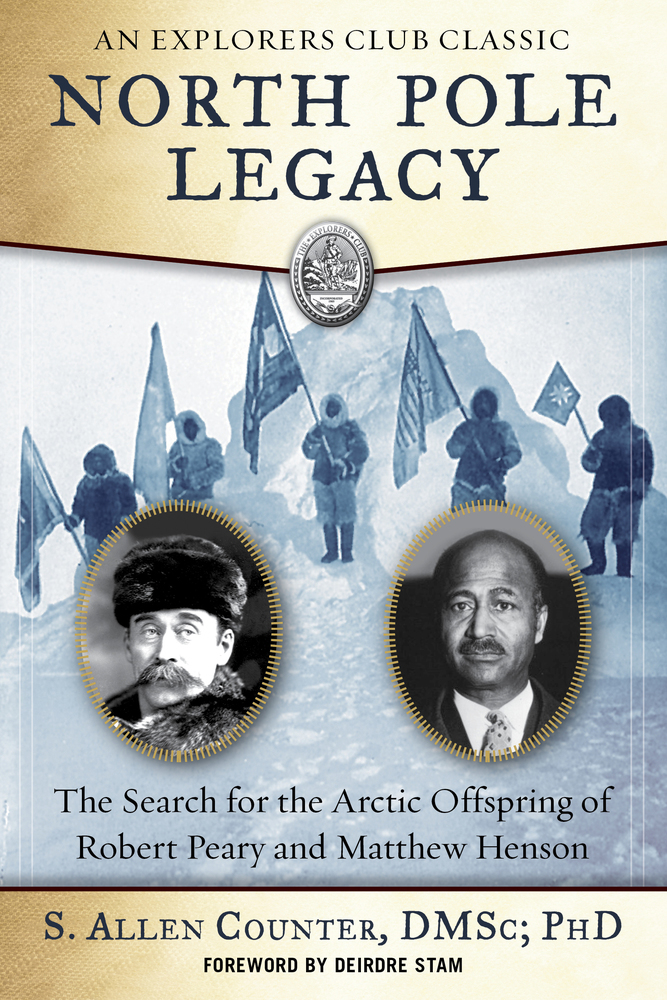

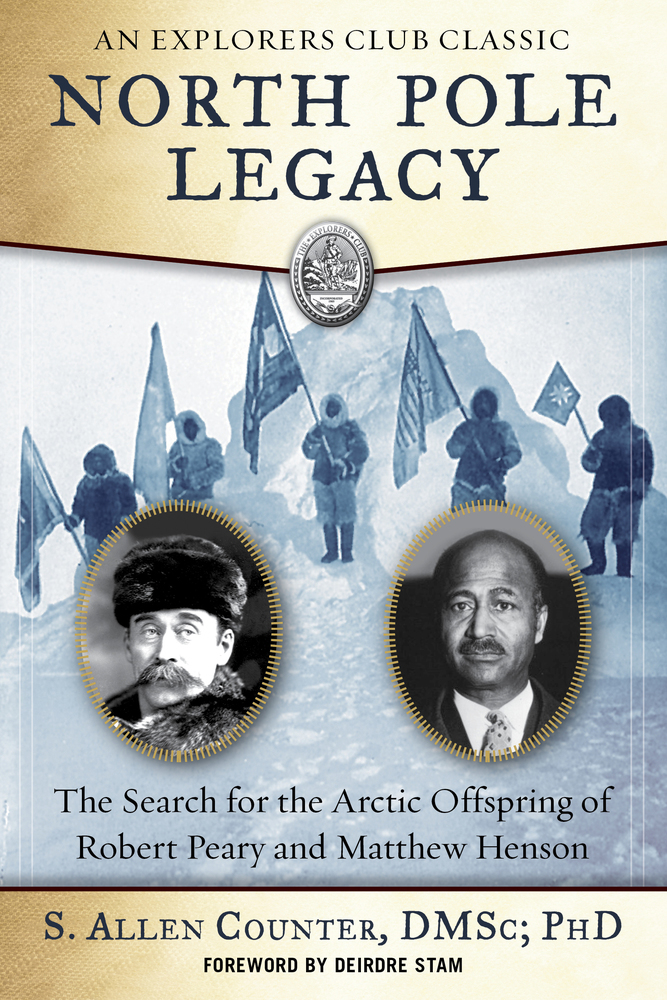

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover photo credit: Background photograph of the Robert Peary Sledge Party Posing with Flags at the North Pole ; Peary and Henson photos courtesy of the Library of Congress

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2637-6

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2638-3

Printed in the United States of America.

DEDICATED TO

Anaukaq and Kali, my friends

Remembered by What I Have Done

Up and away, like a dew of the morning

That soars from the earth to its home in the sun;

So let me steal away, gently and lovingly

Only remembered by what I have done.

My name, and my place, and my tomb all forgotten,

The brief race of time well and patiently run

So let me pass away, peacefully, silently,

Only remembered by what I have done.

Gladly away from this trail would I hasten,

Up to the crown that for me has been won.

Unthought of by man in rewards or in praises

Only remembered by what I have done.

Not myself, but the truth, that in life I have spoken;

Not myself, but the seed that in life I have sown

Shall pass on to agesall about me forgotten,

Save the truth I have spoken, the things I have done.

Sincerely yours

Matthew Alexander Henson

Poem found in Matthew Hensons diary, Matthew A. Henson Collection, Morgan State University, Baltimore.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD TO THE 2018 EDITION BY DEIRDRE STAMM

By the 1980s, when S. Allen Counter began to take an interest in the contact of Arctic explorer Robert Peary and his assistant Matthew Henson with the Greenland Inuit, it may have seemed to most readers that the story of the North Pole conquest was largely played out. The old debate of who got to the magic spot first seemed to have stalled with supporters of Peary and Frederick Cook at loggerheads. New insights into the exploration of the polar region were slow in coming, despite the partisan and non-partisan efforts of astronomers, physicists, mathematicians, historians, latter-day explorers, and nautical experts to find the definitive answer to the Peary-Cook debates over who got there first, or indeed whether either made it at all. There were outposts of research such as the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum and Arctic Studies Center at Bowdoin College, of course, where curators diligently combed through hard evidence of all kinds to piece together a detailed and objective narrative of Pearys years in the Arctic. By then, however, public attention to exploration was focused elsewhere, such as continental Antarctica, outer space, and more mundane but promising regions of scientific research. The human element was certainly considered by researchers in Peary/Henson studies, but more through the lens of the hard rather than soft sciences. There were some exceptions. There had been published anthropological observations of the Inuit culture, most notably by explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson. And interest in Henson largely invoked contemporary racial issues by the 1980s. But in general, public interest in exploration seemed to have turned elsewhere.

Neurophysiologist and social historian Counter introduced a unique blend of methodologies to the understanding of the Peary/Henson experience in the far North with his book North Pole Legacy: Black, White and Eskimo (1991). Acting as participant observer and ultimately as actor in the lives of the explorers Inuit progeny, Counter overcame many physical and administrative barriers to develop personal relationships with the indigenous descendants of Peary and Henson, to elicit community memories of their forebears, and ultimately to bring about meetings in the US of the explorers US and Inuit descendants. Sharing African-American ancestry with Henson, Counter was particularly interested in the life experiences of Henson and his Inuit descendants, and of the possible role of racial prejudice in their lives.

Counter brought storytelling skills to the presentation of his findings, resulting in his highly readable and enlightening book. In doing so, he provided new evidence about the personal interactions of Pearys parties with the Greenland Inuit. Social issues of race, sex, class, motivation, exploitation, and loyalty are addressed indirectly as Counter tells the personal stories of a few dozen Inuit whose lives were intimately affected by their shifting familial relationships to Peary and to Henson.

Those looking for evidence of racial prejudice in Pearys northern ventures can certainly find it, but compared with many contemporaries, he tended to respect ability and practicality when he saw it. While in the North, he lived on intimate terms with those identified as racially different, albeit within constraints of western notions of class and rank. Pearys long-standing relationship to Henson, an African-American considered of lesser social status, provides one example, of such close dependence and physical proximity. Pearys relationship to the Greenland Inuit (or Eskimos in his time) constitute another example. The race question for Henson was more complex. He seemed to have been entirely comfortable with the Inuit, who recognized that his coloration was similar to theirs, and for this and other reasons welcomed him with particular warmth. In fact he is described as living at least as often in Inuit households as with fellow expedition members.

From his Arctic experience and from its literature, Peary developed an appreciation of Inuit men as able hunters, providers, and responsible heads of households. He took full advantage of their skills, rewarding their work with the kinds of remuneration that generated long-term cooperation and loyalty. Peary also appreciated and exploited the skills of Inuit women in turning arctic resources into forms that could be eaten, worn, and enjoyed. He wrote admiringly of their skills: Household duties are as carefully practiced (allowing for differences in materials) as in any domestic circle. (Robert E. Peary, Nearest the Pole , New York, Doubleday, Page & Company, 1907, p. 380.) Inuit women performed their duties while nurturing children in conditions that may strike us today as impossibly uncomfortable, inconvenient, and even hazardous. Although it has made many modern readers uncomfortable to acknowledge this fact, indigenous women were also valued by many Northern adventurers for the companionship and sexual comforts that they could provide to men far from home and lonely for female contact.

Peary himself developed a sexual relationship with a very young, already married woman named Ahlikahsingwah, who bore him two boys. The first, Anaukaq, died young, and the second, Kali, born in 1906, lived well into old age. Henson too maintained a seemingly stable relationship with an Inuit woman named Akatingwah who in 1906 bore Henson one child, also named Anaukaq. He, like Kali, lived into old age. According to Counter, the husbands of these women, who were brothers, in effect adopted the explorers children. Both Kali and (Hensons son) Anaukaq were alive at the time of Counters visit and figure prominently in his story.

Next page