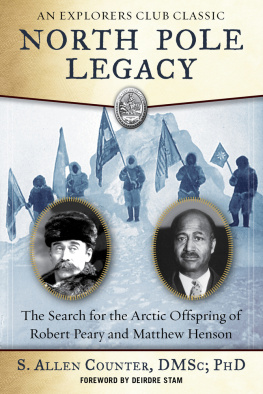

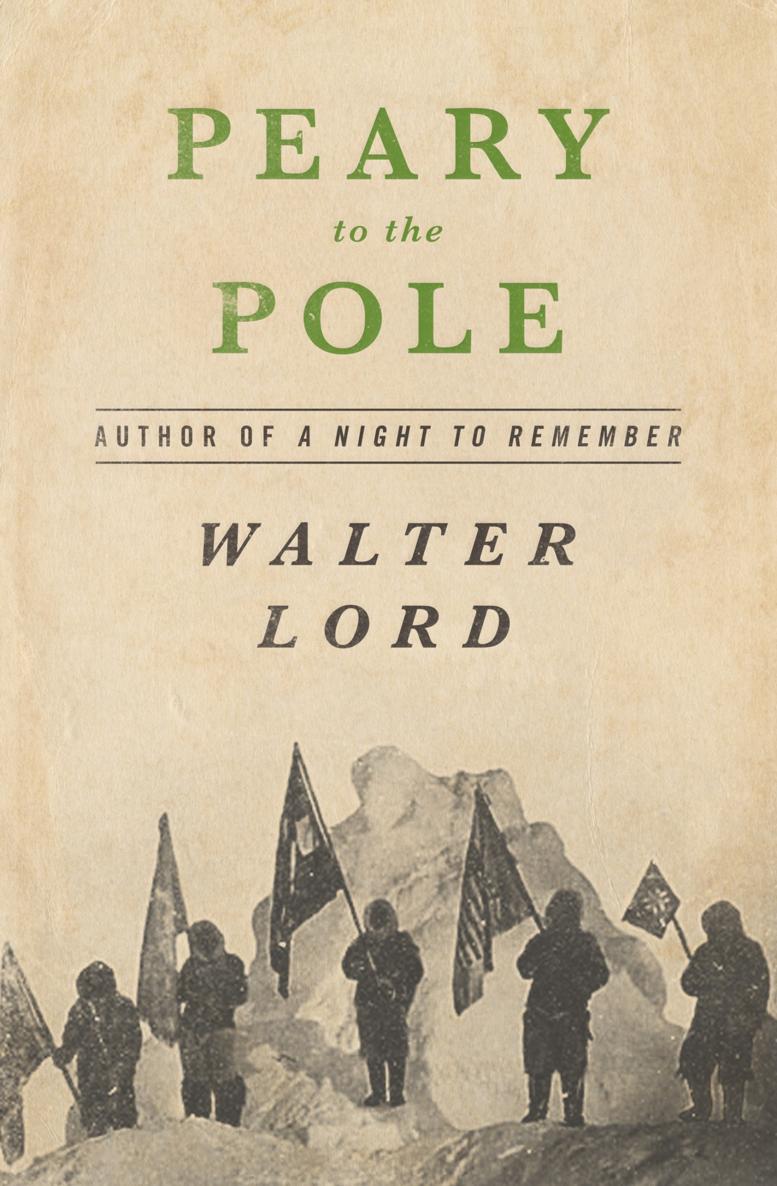

Peary to the Pole

Walter Lord

To John M. Woolsey III

FOREWORD

IN 1906 A THOUGHTFUL historian named John Chisholm Lambert wrote that once the North Pole was discovered, it will be necessary for would-be explorers to sit down, like Alexander the Great, and weep because there are no more worlds to conquer.

Today we know better. The moon, the planets, the starsthere seems no limit. Yet distance is not the measure of discovery. Perhaps the greatest explorer of all was the first man daring enough to paddle his primitive raft beyond the sight of the land he knew.

In this sense, the discovery of the North Pole was a truly momentous event. For centuries men had wondered about it. For decades they had tried to reach it. For twenty-two years Robert E. Peary himself had been dazzled by the idea. When he finally triumphed, his success was more than personalit was a historical breakthrough, over-brimming with that inspirational quality always present when man achieves some long-sought goal.

Walter Lord

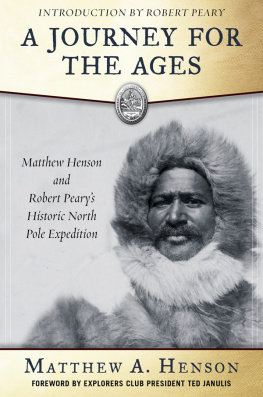

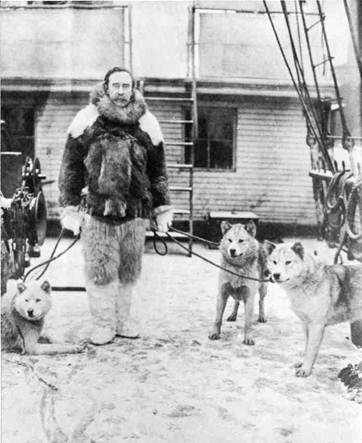

Culver Service

Robert E. Peary stands on the deck of his ship the Roosevelt. For Peary the North Pole was the goal of nearly a quarter of a century of desire and effort. In his fierce determination to reach the top of the world, his resourcefulness knew no limits. These furs, for instance, he adapted from the Eskimos. They were warm at 50 below zero, yet weighed no more than the clothes which the average man wears driving to work in the wintertime.

I

Forward, March!

FORWARD, MARCH! THE COMMAND came in a crisp, clear voice that could be heard even above the howling wind. One by one a little group of fur-clad figures moved out across a jumbled sea of ice, each guiding a heavily laden sledge drawn by seven yelping, frisking dogs.

The group fell into single file and headed north. Above them, the stars danced and twinkled in the queer half-light of an Arctic day. Beneath them, the snow crunched to the tread of their feet. All around them stretched an endless waste of snow and ice. It was bitterly cold50 belowso cold that a bottle of medicinal brandy, which one of the men tried to keep warm against his chest, was soon frozen solid.

Yet the men trudged on, heads bowed against the biting wind that slashed their faces, kept them from speaking, and all but hid them from view as it whipped the powdered snow into a fine icy dust. Bringing up the rear was the man who had ordered them forward, ready to throw his support wherever needed.

His name was Robert Edwin Peary, and he was a commander in the United States Navy. He was a big man with bristling moustache and steel-gray eyes that peered through the fringe of his hooded jacket. Hampered by his furs, he moved slowly, but his heart beat fast, for on this first morning of March, 1909, he was setting out to achieve his lifes dream: to be the first man ever to reach the North Pole.

Now it lay only 413 miles ahead. Not much as distances goabout as far as Boston to Washingtonbut these were miles of solid ice. Worse, it was not ordinary ice the kind that covers a pond or stream. This was sea icethe frozen surface of the Arctic Ocean itself. Strange tides and currents were always at work, leaving treacherous gaps of inky water that seemed just waiting to swallow somebody up. But Peary didnt hesitate as he pushed steadily on.

Behind lay the more familiar world he knew. First, there were the empty igloos at Cape Columbia, the jumping-off place his men had just left. Then, ninety miles behind these, there was the base ship Roosevelt, moored at Cape Sheridan, the farthest north a boat had ever gone. And still farther behind were other things: The memories of twenty-two years of Arctic work, seven expeditions, six attempts on the Pole itselfeach defeated by some unexpected, agonizing turn of events.

Could Peary do it this time? Common sense said no. He had always failed. Yet man can profit by failure too, and buried in these past defeats were lessons important lessons that one day might lead to success.

II

The Thing That I Must Do

IT WAS TWENTY-FIVE YEARS earlier when Robert E. Peary first thought of standing at the top of the world. And it happened not in the frozen north but in the sunny Caribbean.

He was sailing to Nicaragua in 1884 as a young United States naval engineer. At this time there was no canal between the Atlantic and Pacific, and Peary was on a trip to study where one might be built. But as his ship passed the little island of San Salvador his mind was far from canals.

This distant shore had been Columbuss landfall on his first trip to the new world. Now the very sight filled restless twenty-eight-year-old Peary with excitement. What a thrill to have been Columbus! Here was a man, Peary wrote that night in his diary, whose fame can be equalled only by him who shall one day stand with 360 degrees of longitude beneath his motionless feet and for whom East and West shall have vanishedthe discoverer of the North Pole.

At the time it was only natural to think of the Pole this way. The vast, empty Arctic had intrigued men for centuries. At first people hoped that this maze of frozen seas and islands might hide a short cut from Europe to the riches of the Far East, and a long line of explorers searched in vain for what they called the Northwest Passage. Gaspar Corte-Real was doing this for the Portuguese as early as 1500; Henry Hudson was at it for the English in 1610; each country had its heroes.

Later men knew they would never get to the Orient that way, but the fascination of the Arctic remained. It was so big, so dangerous, so unknown. The very mystery of it beckoned anyone who yearned for fame and adventure. But the price was often high. In 1845 Sir John Franklin led two small ships into the ice far north of Hudsons Baythey were crushed by the floes and all 129 men were lost. In 1879 Lieutenant De Long of the American Navy took another small ship, the Jeannette, through the Bering Straits and into the ice far north of Siberia. It too was crushed, and nearly all were lost. In 1881 a young United States Army officer named Adolphus Washington Greely led a small expedition to Fort Conger, to the west of northern Greenland; three years later only six of forty-two survived.

So it went. But each failure only stirred others to greater effort. Gradually most of the Arctic was explored, mapped, and charted, until at last only one final mystery remainedthe greatest of all the North Pole itself.

This now became the goal of everyone. Rich men like Lord Northcliffe of England poured in money. Royalty like the Prince of Monaco and Italys Duke of Abruzzi gave their support. Danes, Russians, Americans, explorers from many nations joined the race to get there first. Every conceivable theory was triednew bases, new kinds of ships, food, and clothingbut in the end the ice and cold always proved too much. Dozens tried, but the Pole remained just out of reach ever more tantalizing, ever more challenging and mysterious.