1

The Worst Thing Ive Seen in 45 Years

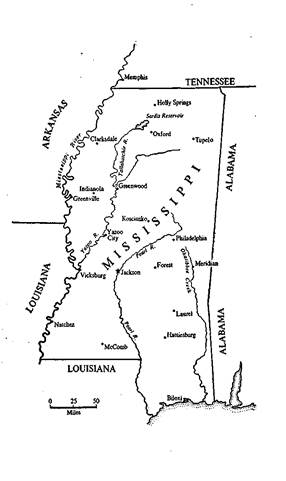

THE EYES OF THE nation and all the world are upon you and upon all of us, said the President of the United States, speaking from the White House on Sunday evening, September 30, 1962. It was a national TV hook-up, but these particular words were addressed to the students of the University of Mississippi. John F. Kennedy was appealing to them to accept on their campus at Oxford a young Negro Air Force veteranthe first of his race ever to win admission to the University.

James H. Meredith had arrived there that afternoon, armed with 60 hours of academic credits, an order from the Supreme Court and several hundred federal marshals. That should have been enough, but for days Mississippi had been in turmoil at the prospect. The Governor had called for defiance, the Confederate flag seemed to fly from every car aerial, and one youth in Jackson was urging that it would be perfectly practical to mobilize private planes and bomb the U.S. Army with napalm.

So President Kennedy had gone on the air at 10:00 (8:00 Mississippi time) and was using every argument he knew. There was the sanctity of the law: if the courts could be defied, no citizen is safe from his neighbors. There was his duty to enforce the laws even if he had to use troops, but he carefully stressed that local means were best. There were the other Southern states that had set such a fine example. There was the rest of the nation that must share the blame for the accumulated wrongs of the last 100 years. And most important, there was the honor of Mississippiher bravery on the battlefield, courage on the gridiron, the patriotism of Senator (later Justice) L. Q. C. Lamar, the great Mississippian who put the nation first.

Let us, concluded the President, preserve both the law and the peace, and then, healing those wounds that are within, we can turn to the greater crises that are without and stand united as one people in our pledge to mans freedom.

Few of the students even heard. By now a full-scale riot was on, swirling about the federal marshals who were deployed around the Lyceum, the Universitys administration building. Meredith had been whisked to a dorm, but few knew that. Bricks, bottles, pipes showered down on the marshals, and even before Kennedy began speaking, the federals were fighting back with tear gas. By the time the President finished, a roaring battle was on.

Kennedy went to the Cabinet Room and sank into his black leather chair. Behind him hovered a handful of aides. Beside him sat his brother Robert, the Attorney General, relaying bulletins that came over the phone from the riot. The news grew steadily worse10:58, marshals running out of gas 11:02, the Mississippi Highway Patrol, the chief hope for law and order on the spot, reported pulling out 11:22, former General Edwin A. Walker, militant right-winger, rumored on the campus 11:23, a marshal shot through the leg 11:42, state trooper hurt bad.

About 11:45 Kennedy was on the phone with Mississippis Governor Ross Barnett, urging him to get the Highway Patrol back. Barnett said hed do everything he could. But the bad news flowed on11:55, FBI radio monitor reported Highway Patrol still without orders to return to campus 11:58, still no orders to the Patrol 12 midnight, gunfire spreading.

Now Deputy Attorney General Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, in charge of the federal forces on the scene, came on the phone. Reluctantly he said the time had come for troops. It was the last thing the President wanted to do, but he didnt hesitate a second. Walking to his oval office, he phoned the Pentagon and put through the orders.

The minutes dragged on, punctuated by more depressing bulletins12:10, only 67 local National Guardsmen immediately available 12:13, U.S. Army regulars, flying down from Memphis, not airborne yet 12:21, troops still not airborne 12:52, 13 wounded now 12:57, state patrolmen still sitting out on the highway. Once, spirits briefly rose with a flash that the troops were at last on the way, but at 1:02 word came that this report was wrongthey hadnt left Memphis yet. Then another message that the men were airborne and at 1:47 another heart breaker, that they were really still in Memphis.

In the end, it was after 2:00 when the little group in the Cabinet Room knew for sure that the troops had not only left but were actually arriving at Oxfords miniature airport. Now at last the White House could breathe easily. It was only a half-mile to campusGeneral Billingslea and his men should be there in three or four minutes. Such calculations made it all the more frustrating when word arrived at 2:55 that there was no sign of the Army yet only new, high-powered rifle fire. Worse, at 3:33 word came that the troops were still at the airport. The Generalstruggling to assemble his men and equipmentthought they could reach the battlefield by four.

John F. Kennedy was not a man to throw his weight around, but the long delay, the mounting bloodshed and, above all, the dashed hopes had done their work. At 3:35 the White House line to the communications base at Oxford crackled with a stern command: tell General Billingslea to move now. The General got and obeyed the order, but he didnt learn the actual text until two hours later, when his men were clearing the campus and the crisis was over. People are dying in Oxford, ran the anguished message. This is the worst thing Ive seen in 45 years. I want the military police battalion to enter the action. I want General Billingslea to see that this is done.

Where did the blame lie for the worst thing in the Presidents 45 years? Certainly not with the troopsthey were moving as fast as they could. Nor with the decision a few days earlier to rely on federal marshalsthat was in the best tradition of civilian government. Nor was it the fault of a month ago, when the Administration first plunged into the Meredith caseit was the Presidents duty to enforce court decisions. No, the real blame lay still further in the pastbeyond the Supreme Courts ban on school segregation, beyond dark decades of apathy and misunderstanding all the way back, in fact, to the blunders and bitterness of a people fighting a desperate civil war.

2

Lest We Forget, Lest We Forget

SPLINTERS FLEW IN EVERY direction as the Union troops hacked away at the chairs and tables of Edward McGehee, a wealthy cotton planter in Wilkinson County, Mississippi. It was October 5, 1864, and Colonel E. D. Osbands men were simply acting on the philosophy expressed by General Sherman when he told a group of protesting Mississippians, It is our duty to destroy, not build up; therefore do not look to us to help you.

Soon the work was done, the house in flames, and Edward McGehee left contemplating his only remaining possessiona gracefully carved grand piano. It was no comfort to Mr. McGehee, once the owner of hundreds of Negro slaves, that these deeds were done by a company of stern, efficient Negro soldiers.