CHAPTER ONE

To All Americans in the World

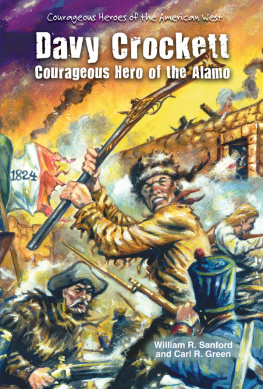

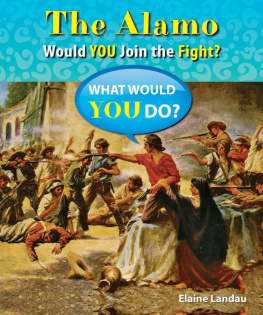

IN THE BARE HEADQUARTERS room of an improvised fort called the Alamo, Lieutenant Colonel William Barret Travis picked up his pen and began to write. Travis was a rebel, commanding some 150 other rebels, in the insurgent Mexican territory of Texas. He was hundreds of miles from the United States bordertwo weeks from New Orleans, a month from Washingtonbut it never occurred to him that his words were of limited application. With bold, unhesitating strokes, he addressed his message To the People of Texas & all Americans in the world.

Outside, his men went about their duties. It was late afternoon, and some were already cooking supper in the large open space that formed the heart of the Alamo compound. Others hoisted the forts best gun, a fine 18-pounder, onto a new mounting. Hot work, for it was surprisingly warm for this time of the yearFebruary 24, 1836.

Still other men crouched behind the walls and barricades, squinting across the flat Texas landscape toward the hills to the north and east, some shanties to the south, or the little town of San Antonio de Bexar directly to the west. Here they could see a red banner flapping from the top of the towns church tower. And occasionally they also saw tiny figures moving about in the distancesoldiers of His Excellency General Antonio Lpez de Santa Anna, President of the Republic of Mexico.

It was growing dark nowa good time for a courier to slip out unseen. Travis scribbled on, filling the page with dashes and hasty abbreviations, somehow in keeping with his quick, abrupt way of doing things. But there was always time to underlineonce, three times a single phraseand this too seemed in character, for he had a great flair for theatrics. Briefly, he explained his situation:

Fellow citizens & compatriotsI am besieged, by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna I have sustained a continual Bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a manThe enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is takenI have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & everything dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatchThe enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor & that of his country- Victory or Death.

A pause; then a short, moralizing postscript: P.S. The Lord is on our sideWhen the enemy appeared in sight we had not three bushels of cornWe have since found in deserted houses 80 or 90 bushels and got into the walls 20 or 30 heads of Beeves.

No time for more. Now to get it out. A tricky assignment, which Travis gave to 30-year-old Captain Albert Martin. He came from Gonzales, the first stop some seventy miles away, and knew the country like a book.

The Alamo gate flew open, and before the startled Mexicans could move, the young Captain galloped off into the dusk. First south along the irrigation ditch then left, onto the Gonzales road. Up the hill, by the white stone walls of the powder house, and out into the country.

Across the dry, little Salado Creek he raced, and on over the bare, winter landscape. No more houses now, just the scrubby mesquite trees, the occasional live oaks, the endless, rolling prairie. The only sound: his horses hoofs, pounding through the silent, empty night.

All next day, the 25th, Martin rode on. Behind him he could hear the distant rumble of a heavy cannonade. They must be attacking, he thought, and rode harder. It was late afternoon when he passed Batemanshis first house the whole dayand headed down into the flatland, or bottom, of the Guadalupe River. He splashed across the ford, up the bank, and onto a straggling little street of one-story frame houses. He had reached Gonzales at last.

Hurry on all the men you can, Martin wrote on the back of Travis dispatch. Young Launcelot Smithers, who would relay the message on, didnt need to be told. He had arrived from the Alamo himself the day before, bringing a brief estimate of the Mexican strength. Now he was rested, ready to ride to San Felipe, next stop to the east.

Smithers galloped off into the night. Ninety miles. The weather had shifted; a hard, icy wind now blasted his earsone of the famous northers which Texans already boasted about with a streak of perverse pride.

It was early Saturday, the 27th, when Smithers finally reached San Felipe. He pounded down the main streetan uneven double row of houses, stores and saloons. This was the metropolis of Texasthe center of business and political life and the news put the place in an uproar. At 11 A.M. the citizens held an emergency meeting and spent the next hour debating and shouting interminable resolutions. Smithers himself, a simple man, seemed closer to the heart of the matter. Adding his own postscript to Travis dispatch, he scrawled, I hope that Every one will Randeves at Gonzales as soon possible as the Brave Soldiers are suffering. do not neglect the powder. is very scarce and should not be delad one moment.

More couriers sped the news on. Fanning out over the faint trails and roads, they headed north for the ambitiously christened new capital, Washington-on-the-Brazos east for the lively gambling town of Nacogdoches south for Columbia and the thriving Gulf settlements.

In ever widening circles, hurry and confusion, alarm and excitement. When the courier stopped by Dr. P. W. Roses place at Staffords Point, Mrs. Rose read Travis message aloud to the children, and 11-year-old Dilue burst into a flood of tears. She recalled the time Travis had stopped at their place and sent her a little comb afterward.

No time for weeping, she was told; she spent the rest of the day melting lead in a pot, dipping it up with a spoon, molding homemade bullets. The older men in the family rushed to get ready for the army, and Mrs. Rose sat up all night sewing two striped hickory shirtsher idea of what a good militiaman should wear.